The early days of the Apple Macintosh were far from the resounding success that defines Apple today. Despite its innovative graphical user interface, the original Macintosh launched with significant limitations. Its hardware, particularly the main memory, struggled to adequately support the demands of the new GUI. Compounding these technical challenges was the absence of a hard drive, severely restricting its capabilities for serious users.

Critics were quick to point out these shortcomings. As Jack Schofield of The Guardian noted two decades later, the initial 128K Mac was plagued with issues. Limited software availability, lack of expandability (no hard drive, SCSI, ADB ports, or expansion slots), underpowered performance, and a high price tag hindered its market appeal. While applications like MacWrite and MacPaint showcased innovative user interaction, performing more complex tasks, even basic operations like floppy disk copying, proved to be cumbersome. The crucial element missing was robust business software, essential for widespread adoption in the corporate world.

In stark contrast, IBM’s PC marketing effectively highlighted its business applications. Apple’s “Software Evangelists,” led by figures like Guy Kawasaki, embarked on a campaign to attract software developers to the Macintosh platform. However, the Mac’s restrictive 128KB ROM presented a significant hurdle. It wasn’t until the introduction of the “Fat Mac” with 512KB of memory a year later that this bottleneck was alleviated, offering developers more room to create powerful applications.

The Mounting Pressure and Sculley’s Intervention

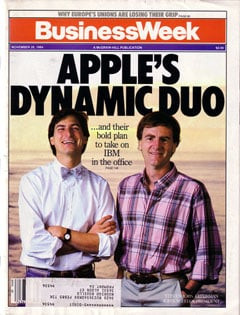

By early 1985, the initial excitement surrounding the Macintosh had waned. Units remained unsold from the previous Christmas season, accumulating in warehouses. This inventory glut led to a significant downturn, forcing Apple to announce its first quarterly loss in company history and implement substantial layoffs, reducing its workforce by a fifth. Amidst this crisis, Apple’s CEO, John Sculley, took decisive action. During a pivotal marathon meeting spanning April 10th and 11th, 1985, Sculley made a firm demand: Steve Jobs, then a vice president and general manager of the Macintosh division, should be relieved of his operational responsibilities.

The Power Struggle and Jobs’ Ousting

Sculley’s plan was to transition Steve Jobs into a figurehead role, an Apple chairman who would represent the company externally but without direct influence over core business operations. However, word of these plans to diminish his authority reached Jobs, and he attempted to orchestrate a counter-move, a coup against Sculley within the Apple board. Sculley, however, confronted the board directly, presenting a clear ultimatum: support his decision to remove Jobs from his operational role, allowing Sculley to take full responsibility for the company’s direction, or face potential leadership changes. The majority of the board sided with Sculley, the seasoned executive recruited from PepsiCo, effectively turning away from the charismatic co-founder, Steve Jobs.

A vintage image depicting the partnership of Steve Jobs and John Sculley, labeled "Apple's Dynamic Duo"

A vintage image depicting the partnership of Steve Jobs and John Sculley, labeled "Apple's Dynamic Duo"

On May 31, 1985, Steve Jobs was officially stripped of his responsibilities and relegated to the position of chairman, a role devoid of real power. Disillusioned and feeling marginalized, Jobs resigned from Apple in September, taking several key employees with him to embark on a new venture: NeXT Computer. In his resignation letter to Mike Markkula, Jobs expressed his deep disappointment, lamenting the lost opportunity to continue creating at Apple. “I feel like somebody just punched me in the stomach,” he wrote, stating his desire to continue contributing and creating, something he felt Apple was denying him. Years later, in the 1996 TV documentary “Triumph of the Nerds,” Jobs reflected on his ousting with bitterness, famously stating, “I hired the wrong guy,” referring to Sculley, and adding that Sculley “destroyed everything I spent ten years working for.”

Reflections from Within Apple

Andy Hertzfeld, a key figure in the Macintosh development team, recalled the tense atmosphere and the board meeting that sealed Jobs’ fate. He described the board’s initial hope of persuading Jobs to accept a product visionary role, but Jobs instead launched an attack, advocating for Sculley’s removal. After extensive discussions, the board ultimately backed Sculley, directing him to reorganize the Macintosh division and remove Jobs from authority.

A photograph of Andy Hertzfeld, a key member of the original Macintosh development team

A photograph of Andy Hertzfeld, a key member of the original Macintosh development team

Hertzfeld openly mourned Jobs’ departure, asserting that “Apple never recovered from losing Steve.” He emphasized Jobs’ role as the “heart and soul and driving force” of Apple, suggesting the company’s trajectory would have been significantly different had he remained. Larry Tessler, who joined Apple from Xerox, noted the mixed reactions within the company. While some felt relief at the departure of the demanding and sometimes “terrorizing” Jobs, there was also immense respect for his vision and charisma, and widespread concern about Apple’s future without its founder.

The Irony of Timing and Sculley’s Regret

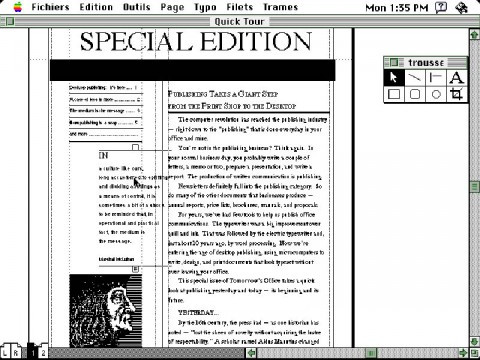

Ironically, as Jobs was being ousted due to the Macintosh’s slow sales, the tide was beginning to turn. The persistent efforts of the “Macintosh Evangelists” and the emergence of crucial software were starting to bear fruit. New software companies like Aldus embraced the “Macintosh Toolbox,” developing groundbreaking desktop publishing applications like PageMaker. Combined with the Apple LaserWriter and Adobe’s PostScript page description language, PageMaker revolutionized the publishing industry. The release of the Mac Plus with expanded memory in early 1986 further solidified the Macintosh’s position.

A screenshot of PageMaker 1.0 (French version), showcasing its desktop publishing capabilities

A screenshot of PageMaker 1.0 (French version), showcasing its desktop publishing capabilities

Another significant twist of fate is that Steve Jobs eventually returned to rescue a struggling Apple. Apple’s acquisition of NeXT in 1997 brought Jobs back into the fold, and he subsequently resumed his role as CEO, leading Apple to unprecedented success.

In a 2010 interview, John Sculley acknowledged Jobs’ monumental contributions to Apple and expressed regret over how their relationship and the events unfolded. Despite not having spoken to Jobs in decades, Sculley conveyed “tremendous admiration” for him. Sculley accepted responsibility for his role in the conflict but also suggested that the Apple board should have recognized Jobs’ need to be in a leadership position. He speculated that different roles, perhaps with Jobs as CEO and himself as president, might have prevented their falling out.

Sculley openly admitted that hiring him as CEO was a “big mistake.” He was not Jobs’ initial choice, but the board, hesitant to appoint a young Jobs as CEO, sought an experienced executive from outside the tech industry. The intention was a partnership, with Jobs focusing on technology and Sculley on marketing. However, Sculley believes that the board should have prioritized a structure that allowed Jobs to be CEO from the outset, recognizing his vision and leadership as crucial for Apple’s long-term success.

Sculley further reflected on critical missteps after Jobs’ departure. He cited the decision to move away from Intel processors to IBM and Motorola’s PowerPC as a “terrible decision in hindsight,” missing the opportunity to leverage a more commoditized platform. He also identified a larger failure: not reaching out to Jobs when Sculley considered leaving Apple in 1993. Faced with Apple’s struggles and an attempted sale of the company, Sculley now believes the “obvious” solution would have been to bring back the visionary founder. He concludes that Jobs’ eventual return was crucial, and without it, Apple might have ceased to exist.