John Dickinson using a quill

John Dickinson using a quill

John Dickinson, often hailed as the “Penman of the Revolution,” played a pivotal role in shaping the foundation of the United States through his powerful writings. A scholar and thinker, John Dickinson articulated the ideals and principles that underpinned the nascent nation. His eloquent pen became a formidable weapon in the fight for colonial rights and the pursuit of American independence.

Born into the landed gentry of Colonial America, John Dickinson benefited from an exceptional education, a privilege afforded to few in the 18th century. This upbringing equipped him to excel in diverse roles: plantation owner, farmer, slaveholder, devout Quaker, family man, businessman, politician, patriot, and ultimately, a Founding Father. His multifaceted life experiences enriched his understanding of the colonies and fueled his dedication to public service.

Crosiadore Plantation Front Elevation

Crosiadore Plantation Front Elevation

John Dickinson’s journey began in November 1732 at Crosiadore, a sprawling plantation nestled in Talbot County, Maryland. His birth cry marked the arrival of a son whose future calls for liberty would resonate throughout Colonial America, shaping the course of history.

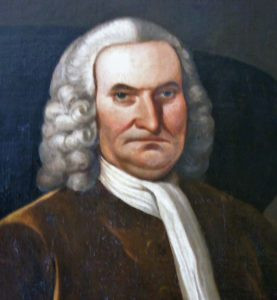

Portrait of Samuel Dickinson, John Dickinson's Father

Portrait of Samuel Dickinson, John Dickinson's Father

His father, Samuel Dickinson, a prosperous landowner, businessman, and lawyer, laid the foundation for John’s privileged life. As a third-generation tobacco planter, Samuel expanded the family’s wealth through shrewd business acumen and the labor of enslaved people.

In 1740, the Dickinson family relocated to Kent County, Delaware. While Samuel’s children from his first marriage inherited the Maryland plantation, John and his brother Philemon thrived in Delaware. Samuel’s esteemed position as a Kent County Judge and Justice of the Peace further solidified their standing in the community.

Growing up at the Jones Neck plantation in Kent County during the mid-1700s, young John Dickinson immersed himself in the family’s agricultural pursuits. His father transitioned from tobacco to grain farming, fostering in John a deep connection to the wheat fields, rivers, and marshes of Delaware. This intimate familiarity with the land shaped his perspective and instilled in him a strong sense of place.

Beyond practical experience, John Dickinson received a rigorous formal education. Tutors, including William Killen, the future first Chancellor of Delaware, guided his studies in ancient languages, classical literature, philosophy, and persuasive writing. This comprehensive education provided John with the intellectual arsenal he would later deploy in his distinguished political career.

In 1750, his father facilitated John’s legal apprenticeship in the Philadelphia office of John Moland, the King’s attorney of Pennsylvania. Despite this advantageous placement, John harbored ambitions to study law in London, following in his father’s footsteps.

In 1753, John Dickinson embarked for England and enrolled in Middle Temple, a prestigious Inn of Court. His time in London proved invaluable. He immersed himself in legal studies under prominent British lawyers and cultivated social connections that would endure throughout his life, broadening his horizons and influence.

Upon passing the bar at Middle Temple, John Dickinson returned to Philadelphia, quickly establishing a successful law practice and leveraging his London social network. His career was taking off, setting the stage for his future political endeavors.

Shortly after his return, the death of his father Samuel led to John inheriting a portion of the Kent County estate. In 1760, he assumed responsibility for managing the farm as an absentee landlord, maintaining his residence and burgeoning career in Philadelphia.

John and Mary Dickinson Teapot, Symbol of their Union

John and Mary Dickinson Teapot, Symbol of their Union

John Dickinson’s personal life intertwined with his professional ascent when he met Mary Norris. Mary was the daughter of Isaac Norris Jr., the Speaker of the Pennsylvania Assembly, a wealthy Quaker who bequeathed Mary a substantial inheritance. Their subsequent marriage in 1765 proved to be a significant union.

This marriage deepened John Dickinson’s social and political ties in Philadelphia and granted him control over considerable Pennsylvania property. The combined wealth of the Dickinson and Norris families provided him with the financial independence to dedicate himself to a long and impactful political career, a luxury not available to many of his contemporaries.

Despite his Philadelphia life, John Dickinson remained deeply connected to his Delaware lands. Recognizing Philadelphia as the epicenter of political power, his landholdings in both Delaware and Pennsylvania afforded him the flexibility to seek and hold office in either colony, expanding his political reach.

In 1760, Kent County, Delaware elected John Dickinson to the Delaware Assembly, which convened at the New Castle Court House. Just two years later, Philadelphia chose him to represent them in the Pennsylvania Assembly, demonstrating his growing political prominence and widespread appeal.

In 1764, John Dickinson boldly entered the political fray, opposing Benjamin Franklin and Joseph Galloway’s proposal to transform Pennsylvania into a royal colony. This stance, though unpopular with influential figures, foreshadowed his future decisions and unwavering commitment to principle.

This early political act marked the beginning of his journey as the “Penman.” His pamphlet, “The Late Regulations,” critiqued the Sugar Acts of 1764, articulating the widespread American concern that Parliament was infringing upon colonial rights and threatening economic stability. As the American Revolution drew nearer, John Dickinson’s insights and arguments gained national significance.

During the Stamp Act Crisis of 1765, John Dickinson emerged as a leading voice against the Parliamentary acts imposing taxes through mandatory stamp purchases on various items, including official documents and playing cards. His articulate opposition galvanized colonial resistance.

The Stamp Act Congress entrusted John Dickinson with drafting the “Declaration of Rights and Resolves,” a petition sent to the King of England. This document marked a historic moment as the first official expression of unified colonial sentiment, agreed upon by representatives from multiple colonies.

John Dickinson’s most enduring contribution and the origin of his “Penman” moniker was the publication of “Letters from a Farmer in Pennsylvania to the Inhabitants of the British Colonies” in 1768. Published serially and signed simply “A FARMER,” these letters addressed the contentious Townshend Acts.

Dickinson masterfully argued that the Townshend Acts were unconstitutional, as they aimed to raise revenue, a power he asserted belonged solely to the colonial assemblies. His arguments, presented with clarity and precision, resonated deeply with the general population throughout the colonies and even across the Atlantic in England and France.

The “Letters” catapulted John Dickinson to fame. Voltaire, the renowned French philosopher, likened him to Cicero, the revered Roman statesman, orator, and philosopher, recognizing the power and eloquence of Dickinson’s prose. In Boston, Samuel Adams and other patriots publicly expressed their gratitude, stating “that the thanks of the town be given to the ingenious author of a course of letters… signed ‘A FARMER,’ wherein the rights of the American subjects are clearly stated and fully vindicated.”

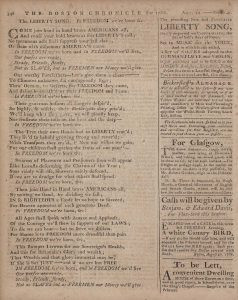

Liberty Song Lyrics Sheet

Liberty Song Lyrics Sheet

1768 also saw another significant creation from John Dickinson’s pen, this time not a pamphlet, but a song. He penned the lyrics to “The Liberty Song,” set to the tune of “Hearts of Oak.” This patriotic anthem quickly gained immense popularity throughout the colonies, becoming a rallying cry for the burgeoning revolutionary movement. Its impact was so profound that the British even composed a rebuttal song using the same melody, highlighting the power of Dickinson’s words to ignite passions.

As colonial tensions escalated, John Dickinson consistently advocated for a moderate approach, seeking redress of grievances through constitutional means. He believed in reasoned discourse and peaceful resolution whenever possible.

Serving as a Pennsylvania delegate to the First Continental Congress, Dickinson was tasked with rewriting a petition to the King, initially penned by Patrick Henry. The Congress deemed Henry’s language too radical, entrusting Dickinson to craft a more conciliatory appeal.

The Continental Congress again called upon John Dickinson to write “Address to the inhabitants of the Province of Quebec,” urging them to join the American colonies in opposing British encroachment on their rights. These commissions solidified Dickinson’s position as the preeminent writer of the Congress, a unique honor.

John Adams, a keen observer of his contemporaries, noted in 1774, “a very modest man, and very ingenious as well as agreeable…[He] is but a shadow. Tall, slender as a reed, pale as ashes. One would think at first sight he could not live a month. Yet upon more attentive inspection he looks as if the springs of life were strong enough to last many years.” Adams captured Dickinson’s physical fragility but also his inner strength and intellectual vitality.

Despite his public prominence, John Dickinson remained humble. In a letter to fellow Delaware politician George Read, he confessed, “…I confess I should like to make an immense bustle in the world, if it could be made with virtuous actions. But, as there is no probability of that, I am content if I can live innocent and beloved by those that I love….” This reveals his desire for virtuous action over mere fame.

John Dickinson’s moderate stance became even more pronounced during the Second Continental Congress. In 1775, he collaborated with Thomas Jefferson on the “Declaration of Causes and Necessity of Taking Up Arms.” Dickinson, with Congressional support, revised the document to reflect a more conciliatory tone, hoping to avert a complete rupture with Britain.

The final major effort to prevent a split was the “Olive Branch Petition,” drafted by Dickinson. However, Britain’s rejection of this petition paved the way for Richard Henry Lee’s motion for independence in June 1776. While figures like Jefferson and Franklin drafted the Declaration of Independence, John Dickinson chaired the committee tasked with planning a new colonial government, the Confederation.

Though recognizing the inevitability of independence, John Dickinson opposed its timing, arguing for postponement until the colonies were more united and had secured foreign alliances. He prioritized pragmatism and preparedness.

“I know that the tide of the passions and prejudices of the people at large is strongly in favor of independence. I know too, that I have acquired a character and some popularity with them — both of which I shall risk by opposing this favorite measure. But I had rather risk both than speak or vote contrary to the dictates of my judgments and conscience.” – John Dickinson’s speech against the motion of independence, demonstrating his courage to stand by his convictions.

His principled stance against immediate independence led to public disapproval. Seeking refuge, John Dickinson retreated with his wife and daughter to his Kent County plantation. However, even his boyhood home could not escape the turmoil of the Revolution. In 1781, it was vandalized by Tory raiders, a stark reminder of the conflict’s reach.

Remarkably, John Dickinson became one of only two members of the Continental Congress to take up arms. He served briefly as a private in the Delaware Militia and effectively supplied Delaware troops. Appointed Brigadier General, he declined the commission, perhaps recognizing his greater strength lay in civilian leadership.

Delawareans demonstrated their continued faith in John Dickinson by electing him to the Executive Council in 1781, marking his return to political life. Their confidence deepened when he was chosen President of Delaware that same year. His service extended further when he became President of Pennsylvania in 1782.

John Dickinson’s dedication to the nascent nation persisted. Representing Delaware at the Annapolis Convention in 1786, convened to discuss navigation rights, he contributed to the growing recognition of the need for a stronger national government.

At the Constitutional Convention of 1787, John Dickinson served as a Delaware delegate, staunchly defending his state’s interests. He famously declared to James Madison, “Delaware would sooner submit to a foreign rule than be deprived in both branches of an equality of suffrage and thereby be thrown under the domination of the larger states,” when larger states proposed representation based solely on population.

His advocacy for state equality proved crucial to the Great Compromise, ensuring equal representation for states in the Senate and proportional representation in the House of Representatives. This compromise addressed a fundamental point of contention and paved the way for the Constitution’s creation.

John Dickinson also championed the inclusion of a provision to prohibit the importation of slaves, reflecting his personal convictions, as he had already freed his own slaves. Though unsuccessful in this broader effort, his stance underscored his evolving views on slavery.

He wholeheartedly supported and signed the Constitution. His influence may have contributed to Delaware becoming the first state to ratify the document on December 7, 1787, a testament to his persuasive abilities and standing within the state.

Following ratification, a series of essays signed “Fabius,” elucidating and defending the Constitution, appeared in newspapers. These were penned by none other than John Dickinson, the “Penman of the Revolution,” once again using his writing to shape public understanding and support for the new government. These “Fabius Letters” are credited with aiding the Constitution’s eventual adoption across the states.

With the new Constitution established, John Dickinson’s extensive political expertise became less central to the nation’s immediate needs. Increasingly, illness curtailed his activities. His monumental contributions to the nation’s founding provided a solid foundation for a well-deserved retirement.

He established a home in Wilmington, Delaware, strategically located between his beloved “Poplar Hall” plantation in Jones Neck and Philadelphia, the city cherished by his wife Mary. This location symbolized the balance he sought in his life.

John Dickinson never neglected his Kent County lands, regularly visiting to manage plantation affairs and oversee tenants, maintaining his deep connection to his agricultural roots.

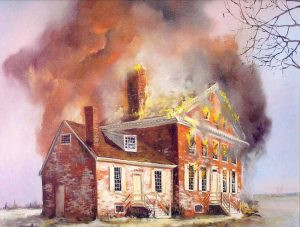

Illustration of the John Dickinson Plantation Mansion Fire

Illustration of the John Dickinson Plantation Mansion Fire

In 1804, a fire tragically destroyed Dickinson’s boyhood home. Under his meticulous direction, the house was rebuilt, reflecting his enduring attachment to the place. In a letter to his wife, he wrote of the rebuilt plantation, “This place affords a luxuriant prospect of plenty…,” expressing his deep connection to the land and its bounty.

John Dickinson’s life was marked by extraordinary accomplishments. His well-deserved title, “Penman of the American Revolution,” stems from his authorship of pivotal petitions and state papers preceding the Revolution. His influence extended across the new nation and within Delaware, lasting even beyond his death in 1808.

“…A more estimable man or truer patriot could not have left us. Among the first of the advocates for the rights of his country when assailed by Great Britain, he continued to the last the orthodox advocate of the true principles of our new government, and his name will be consecrated in history as one of the great worthies of the Revolution…” – Thomas Jefferson, in a letter upon hearing of Dickinson’s death, eloquently summarized his lasting impact.

Today, visitors to the John Dickinson Plantation can explore John Dickinson’s life and legacy. The historic boyhood home, flanked by reconstructed farm buildings and a tenant/slave quarter, offers an immersive experience into the world he inhabited. Interpreters in period attire bring history to life, discussing Dickinson’s impact and the lives of those around him.

While John Dickinson identified as a “Farmer,” a visit to the John Dickinson Plantation reveals the multifaceted dimensions of his life. The sights, sounds, and even smells of the plantation – from cornbread baking to musket fire and flax spinning – transport visitors back in time, fostering a deeper understanding of the man who penned pivotal documents and helped shape a nation, truly a “great worthy of the Revolution.”

To delve deeper into this topic and Colonial Delaware history, reach out to the Delaware Division of Historical & Cultural Affairs, part of the Department of State. They manage the John Dickinson Plantation, the New Castle Court House, and the Old State House in Dover, all offering further insights into John Dickinson’s era.

Related Topics: John Dickinson Plantation, Museums, The Penman of the Revolution