My kids have recently become obsessed with “The Sound of Music,” and like many, I’ve known its songs for years, but only now truly appreciated the film. It’s Rodgers and Hammerstein’s final masterpiece, and its impact is undeniable. Hearing “My Favorite Things” again, I was struck by the melody, but it wasn’t until I considered John Coltrane’s interpretation that I truly understood its depth.

John Coltrane, however, didn’t just think about the tune; he reimagined it entirely on his iconic album, also titled “My Favorite Things.” Released just a year after “The Sound of Music” debuted on Broadway, Coltrane’s version must have been astonishingly unconventional for its time. Imagine if a contemporary artist like Kendrick Lamar suddenly released a 13-minute avant-garde jazz rendition of a popular Disney song – that’s the level of transformation Coltrane achieved.

In Lewis Porter’s insightful biography, John Coltrane: His Life and Music, it’s revealed that Coltrane wasn’t pressured by his label to record “My Favorite Things,” nor did he consider it beneath him. In fact, Coltrane expressed admiration for the song, stating he “would love to have written it” (p. 182) and even considered it his favorite among his own recordings (p. 184). The public agreed, making the album a significant success, especially within the jazz genre.

“My Favorite Things” held a deep significance for John Coltrane, becoming a constant feature in his performances throughout his career. Consequently, numerous live recordings exist. A notable example from 1965 features McCoy Tyner and Elvin Jones, the same pianist and drummer from the studio album, showcasing their enduring synergy.

Coltrane’s live performances of “My Favorite Things” evolved, becoming longer and more exploratory over time. A 1966 recording from Japan stretches to almost an hour, demonstrating the song’s capacity for improvisation and Coltrane’s evolving musical vision.

The studio version of Coltrane’s solos has been extensively analyzed, with transcriptions readily available for musicians and enthusiasts alike. Similarly, McCoy Tyner’s piano contributions have also been the subject of scholarly attention, offering insights into his unique modal approach.

Sami Linna’s dissertation, McCoy Tyner, Modal Jazz, and the Dominant Chord, stands out as a particularly valuable academic resource for understanding Tyner’s playing style within this context. Based on Linna’s transcriptions, rhythm section patterns reveal the intricate interplay between piano, bass, and drums.

“My Favorite Things” is a quintessential example of a jazz waltz, characterized by its 3/4 time signature (“one two three, one two three”), contrasting with the more common 4/4 time. A defining rhythmic feature is the accented “and” of beat one, an unexpected offbeat emphasis that creates rhythmic tension. Combined with a wide swing feel, this accent lands significantly closer to beat two, resulting in a pronounced rhythmic dissonance. However, as with harmonic dissonance, rhythmic dissonance is context-dependent. Over the course of Coltrane’s extended performances, this initially jarring accent becomes normalized, evolving into a new form of rhythmic consonance. Traditional waltzes begin to sound conventional in comparison.

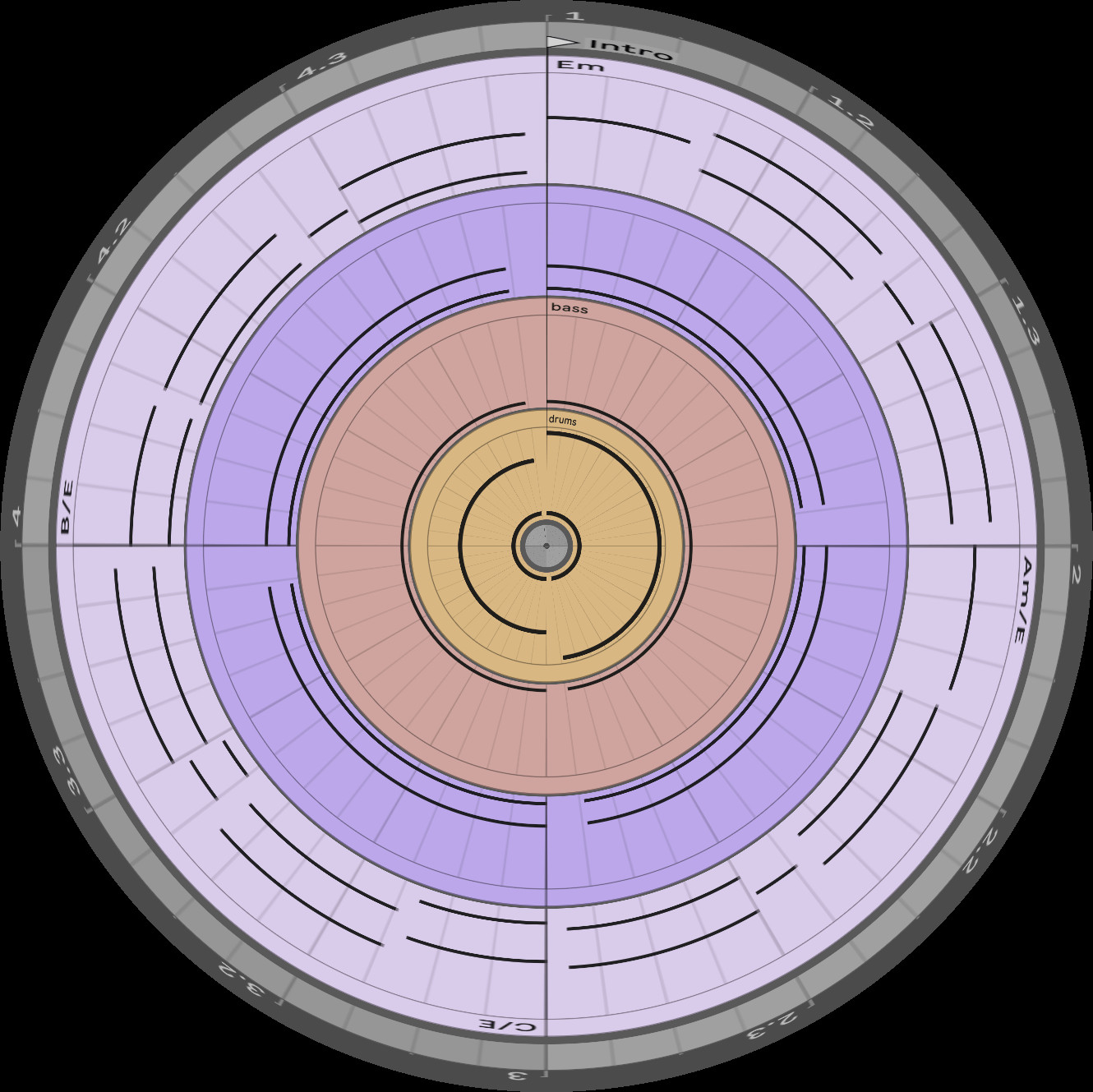

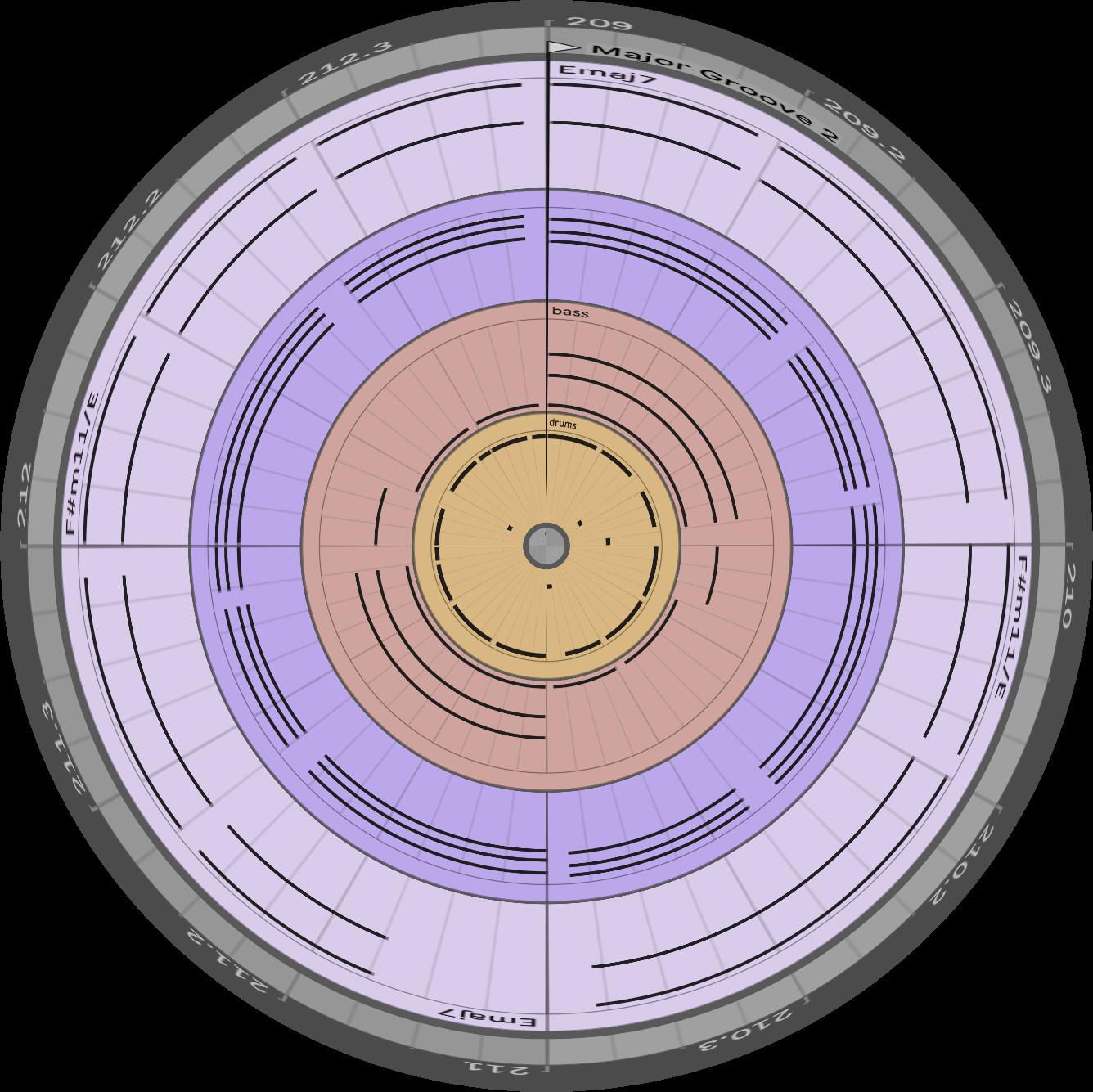

Circular MIDI representation of the intro to John Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things”, showcasing piano, bass, and drum patterns.

McCoy Tyner’s piano riffs can be visualized using tools like Groove Pizza, illustrating the interplay between the kick drum (left hand rhythm) and snare drum (right hand rhythm). Similarly, Elvin Jones’ drum patterns in “My Favorite Things” are distinctive and contribute significantly to the song’s unique rhythmic texture.

The rhythmic complexity and tension are juxtaposed with the harmonic simplicity of “My Favorite Things.” Bassist Steve Davis maintains a drone on an open E string for almost the entire 13-minute recording. While some have linked this drone to Ravi Shankar’s influence, it’s important to note that Coltrane’s deep dive into Indian music occurred after this recording. Coltrane was simply drawn to the musical potential of pedal points and drones, elements found across diverse musical traditions globally.

The structure of “My Favorite Things” deviates significantly from typical jazz forms. Instead of the conventional head-solos-head structure, Coltrane intersperses sections of the main melody with harmonically static, open-ended solo sections. While terms like “vamps” are sometimes used to describe these sections, they are far more than mere placeholders. They are central to the arrangement, providing the foundation for improvisation and exploration. Therefore, “grooves” is a more fitting descriptor, emphasizing their active and integral role in the musical architecture.

A Deep Dive into the Arrangement: Section by Section

Intro (0:00)

The introduction features an enigmatic series of fourths and seconds, concisely encapsulating the harmonic landscape of the entire piece within just four bars. Its structure is visually represented in the circular MIDI diagram, revealing the layered interplay of piano, bass, and drums.

Minor Groove (0:08)

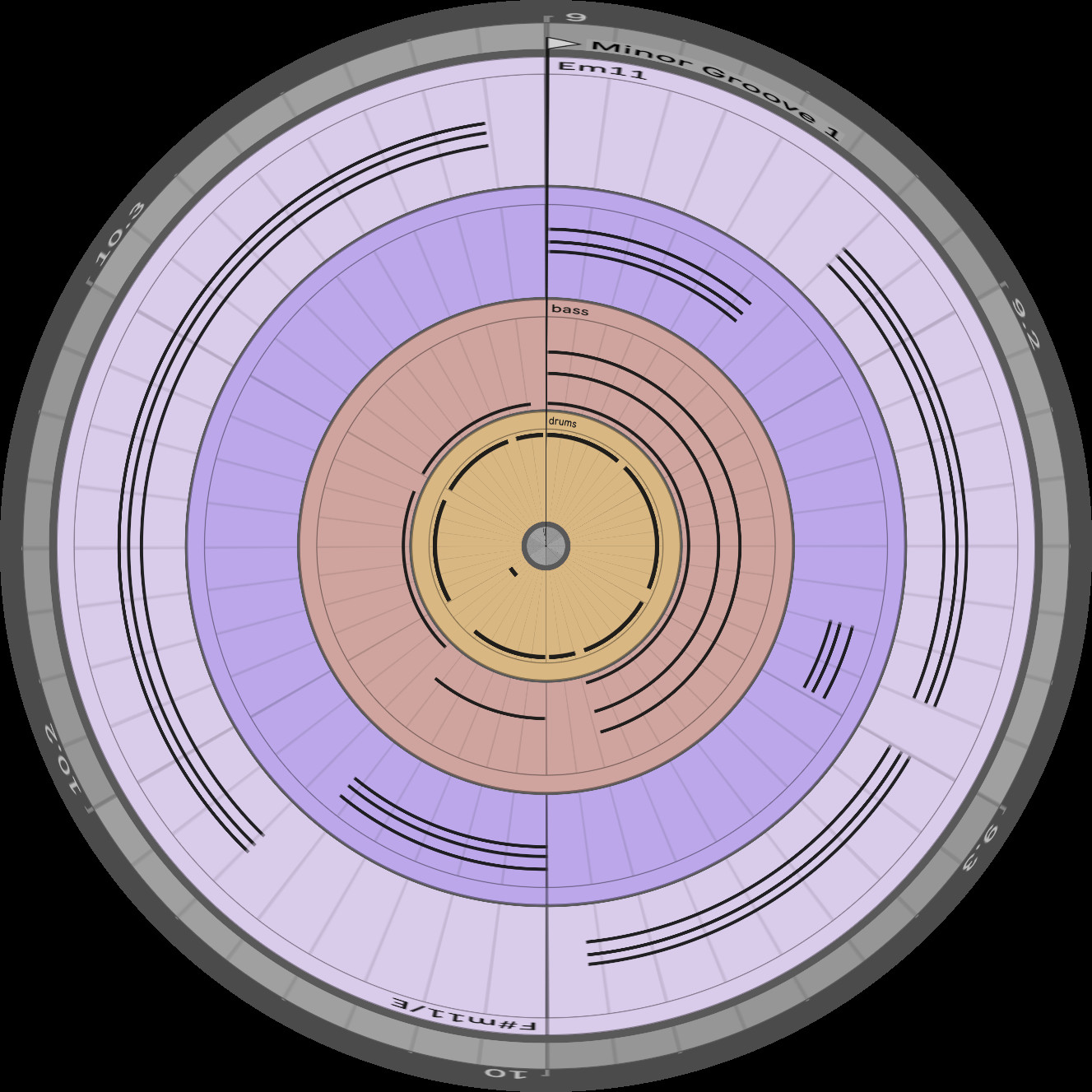

Labeled “Minor Groove 1,” this section introduces peculiar chord voicings. McCoy Tyner’s initial chord is an Em11, which can be interpreted as an E minor triad overlaid with a D major triad. This creates a rich, ambiguous sound, simultaneously suggesting an extended E minor chord and two distinct harmonic entities. Notably, Em11 contains six of the seven notes in the E Dorian mode, evoking a sense of the entire scale within a single chord.

Diagram of “Minor Groove 1” from John Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things”, illustrating chord voicings and rhythmic patterns.

The subsequent chord, F#m11, is essentially Em11 transposed up a whole step. F#m11 also largely aligns with E Dorian mode, with the exception of G-sharp, a major third above E. While the G-sharp might seem to clash with the minor tonality of E Dorian, this major-minor interplay is a hallmark of blues tonality. Although “My Favorite Things” may not overtly sound like the blues, the blues influence is subtly present in Coltrane and Tyner’s musical language.

Head – A Section (0:17)

This section presents the iconic “raindrops on roses and whiskers on kittens” melody. Sami Linna’s dissertation provides a detailed transcription and analysis of Coltrane’s arrangement of this section.

Minor Groove (0:35)

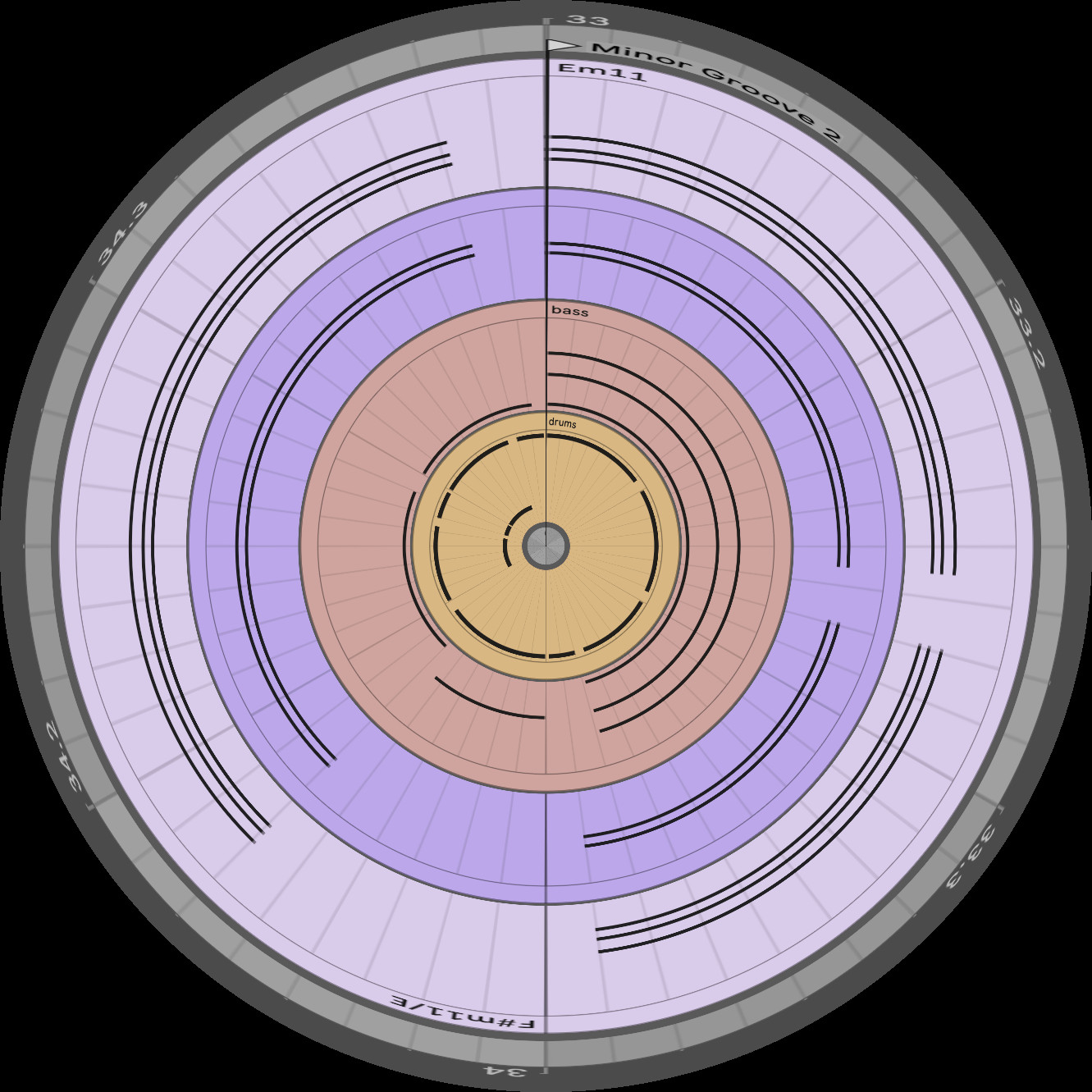

Returning to the Em11 to F#m11 chord progression, “Minor Groove 2” features a different rhythmic pattern, adding subtle variation to the established harmonic foundation.

Visual representation of “Minor Groove 2” from “My Favorite Things”, highlighting rhythmic and harmonic variations.

Head – A Section (0:43)

The melody returns with “cream-colored ponies and crisp apple strudels,” mirroring the first A section in its melodic and harmonic content.

Major Groove (1:01)

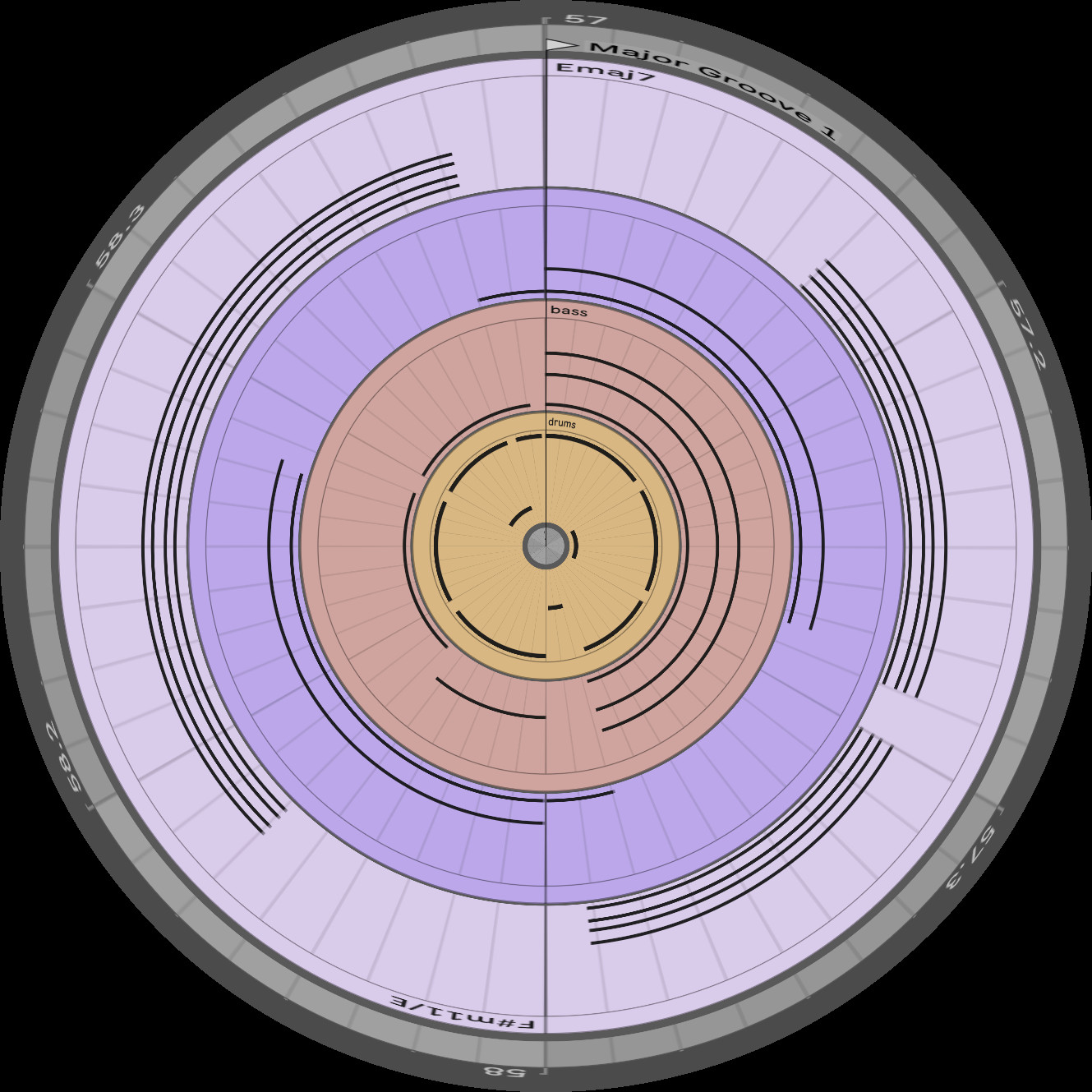

A sudden shift to a brighter mood, the “Major Groove 1” introduces Emaj7 and F#m11 chords, the latter now fitting seamlessly within the major key context.

Diagram illustrating “Major Groove 1” in “My Favorite Things”, showcasing the shift to a major tonality.

Head – B Section (1:26)

“Girls in white dresses in blue satin sashes” marks the B section, structurally similar to the A sections but beginning on Emaj7 instead of Em.

Head – A Section (1:44)

A return to the minor-tinged “raindrops on roses” melody, reinforcing the cyclical nature of the arrangement.

Minor Groove (2:01)

Coltrane introduces tension by trilling B and C natural notes, creating a striking clash against the E Dorian backdrop.

Head – A Section (2:18)

McCoy Tyner takes over the “raindrops on roses” melody, employing a tighter rhythmic precision compared to Coltrane’s earlier rendition.

Minor Groove (2:35)

Tyner explores “Minor Groove 1” with varied voicings. In a departure from typical jazz soloing, Tyner’s playing assumes a more background role, foregrounding the groove itself and demanding focused listening.

Head – A Section (3:08)

Tyner performs the “cream-colored ponies” melody, maintaining the interplay between melodic and groove-based sections.

Major Groove (3:25)

“Major Groove 2” and related patterns constitute Tyner’s most extended solo section. However, even here, he maintains a groove-oriented approach, structuring his improvisations around repeating rhythmic units. His soloing style draws more from James Brown’s groove-centric music than from bebop’s linear melodic approach.

Visual representation of “Major Groove 2” from “My Favorite Things”, showing the extended and varied rhythmic patterns.

Head – B Section (5:56)

Tyner presents “girls in white dresses” in a chordal, abstracted manner, further emphasizing the harmonic framework.

Minor Groove (6:12)

Tyner revisits “Minor Groove 2” with different voicings, building intensity before transitioning back to “Minor Groove 1.” The sustained repetition creates almost unbearable tension, which Tyner masterfully manages by reducing volume, rather than resolving it.

Head – A Section (6:45)

Tyner returns to “raindrops on roses,” maintaining conviction but with a less aggressive delivery, showcasing dynamic control.

Minor Groove (7:01)

Coltrane re-enters, resuming his Dorian-mode-defying B and C natural trills, escalating the tension.

Head – A Section (7:10)

Coltrane plays “raindrops on roses,” reasserting his melodic presence before launching into extended improvisation.

Minor Groove (7:26)

Coltrane’s first extended solo section marks the beginning of truly ecstatic and transportive playing. He alternates between sustained chord tones, simple pentatonic scales, and rapid chromatic and atonal runs. While Coltrane was relatively new to the soprano saxophone at this time, his occasional intonation wavering adds to the searching, yearning quality of his performance.

Head – A Section (9:43)

Coltrane revisits “cream-colored ponies,” the eighth iteration of this melody section, highlighting its structural significance.

Major Groove (9:59)

Coltrane’s second extended solo section is even more ecstatic and transportive than the first. By the 12:00 mark, he transcends rhythmic constraints, rapidly alternating between high-register B/C-sharp trills and low-register major seventh arpeggios, creating the sonic illusion of multiple voices. Remarkably, this is still relatively restrained compared to his later, more avant-garde playing. Throughout this, Tyner and Davis maintain their unwavering groove, while Elvin Jones, though slightly freer, remains grounded. This contrast between the anchored rhythm section and Coltrane’s soaring improvisation is extraordinary.

Head – B Section (12:16)

Coltrane plays “girls in white dresses,” highlighting a subtle structural detail: the first four bars of each melody section share the same chords as the preceding groove. This blurs the lines between groove and melody, suggesting Coltrane’s broader musical aims. He wasn’t simply aiming to modernize show tunes with jazz harmonies; he sought to connect jazz to deeper, more ancient musical traditions, evoking the music of Africa, Asia, and the Middle East, and imbuing his music with a sense of devotional practice. These ideas, further explored in his subsequent albums, are already subtly present in “My Favorite Things.”

Head – C Section (12:33)

Finally, after nearly thirteen minutes, the “When the dog bites, when the bee stings” C section appears. This is the first truly contrasting melodic material, initially melancholic but ultimately resolving to an upbeat major key in the original “Sound of Music” version. Coltrane, however, concludes in a downbeat manner, returning to E minor, specifically the darker E natural minor, rather than the ambiguous E Dorian/blues tonality heard earlier.

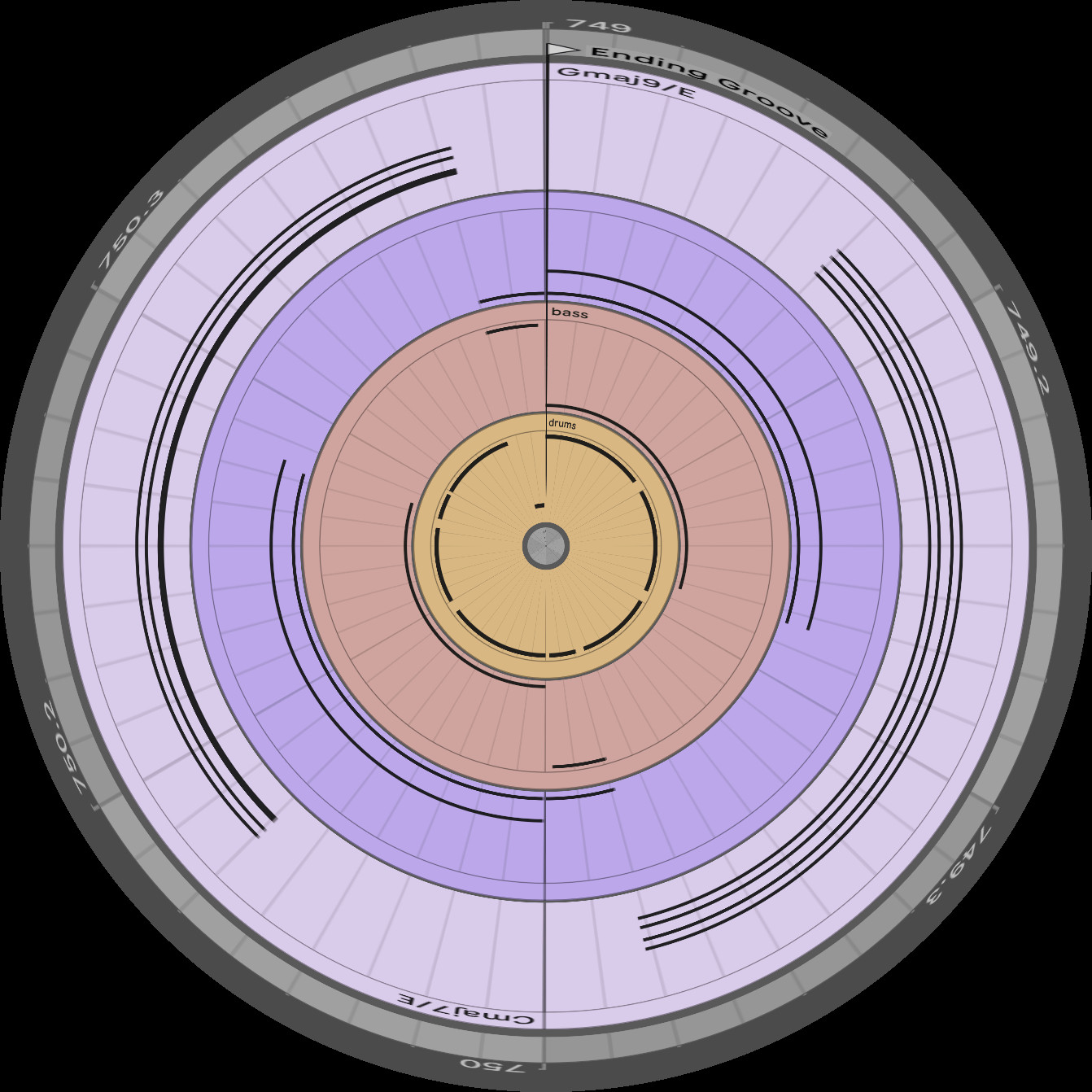

Ending Groove (12:49)

The “Ending Groove” section, unsurprisingly, brings the piece to a close. Linna analyzes the chords as Gmaj9/E and Cmaj7/E. Similar to the Dorian-influenced chords earlier, these can be interpreted as sophisticated voicings of Em, or as richer, independent harmonic entities, mirroring the multifaceted nature of the entire composition.

Diagram of the “Ending Groove” in John Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things”, illustrating the final harmonic and rhythmic patterns.

“My Favorite Things” often serves as an entry point into Coltrane’s vast musical world, and for good reason. It’s an intriguing introduction. Listeners encounter a legendary jazz musician revered for his spiritual depth, yet his most famous recording is a show tune. However, deeper listening reveals the underlying logic. Coltrane frequently interpreted pop songs without irony or condescension. He also explored waltzes from musicals, folk traditions, and spiritual sources. In his hands, this diverse musical material coalesces into a unified expression of ancient, profound religiosity. Coltrane’s ability to perceive beyond the surface of music, transcending cultural boundaries to uncover deeper connections, remains a constant source of inspiration.

Update: Vinnie Sperrazza offers insightful observations on Elvin Jones’s crucial role in this recording:

Attention must be paid to Elvin Jones. In 1960, Jones was the only drummer in jazz who could have gotten Trane’s arrangement of “My Favorite Things” off the ground. Throughout, Elvin subtly alters his volume and density, with constant micro variations on his basic time-keeping pattern. He never once plays a dramatic fill, and rarely even leaves his ride cymbal. More to the point, on “My Favorite Things”, Elvin’s storied rolling triplets are, maybe for the first time, being used to their fullest musical potential: Elvin’s burbling brook is gently inducing a trance.

Throughout, Tyner’s and Jones’ relative restraint is astonishing, and key to the success of “My Favorite Things”. They didn’t play like this on any other tracks they recorded with Trane in late October 1960! Though I can’t imagine them talking about it, it must have been an intentional choice on Elvin’s and McCoy’s part to play as they do on this song.

As McCoy and Elvin churn, drawing our attention to tiny changes in the rhythm, major and minor tonality are no longer opposed, nor ranked in a hierarchy, but simply alternate and coexist. With the trance-inducing rhythms of McCoy Tyner and Elvin Jones, “My Favorite Things” doesn’t need to move forward in time, it doesn’t use melody and harmony to create forward motion.

Coltrane’s “My Favorite Things” implies the minimalism of Steve Reich (a committed Coltrane fan, also a keen observer of Kenny Clarke!) and Phillip Glass; suggests myriad musical traditions outside the USA; connects jazz to the coming rock and psychedelic soul movements; it looks ahead to ambient music. Going backward, it’s merely the latest in a long line of Broadway tunes given new life by jazz musicians, a practice going back to Louis Armstrong.

Coltrane’s music is deeply serious, freighted with the spiritual and musical progress he undertook as the work of his life. But if John Coltrane’s music was only as “serious” as I sometimes took it to be, it would not (and could not) have touched so many people over such a distance of time and place. Coltrane, Tyner, and Jones’ music communicates, with great intensity, all their favorite things, all the beauty and joy sitting next to the pain and sorrow.

Sperrazza’s insights beautifully articulate the nuanced interplay within Coltrane’s quartet and the profound impact of “My Favorite Things,” solidifying its place as a landmark recording in jazz history.