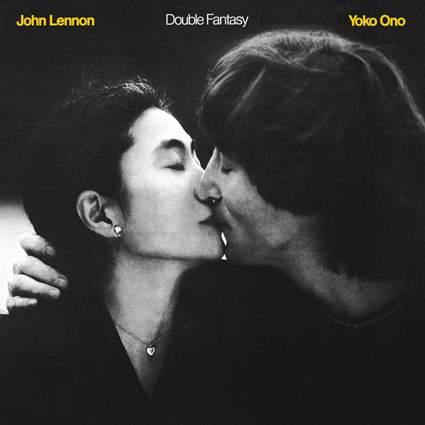

John Lennon Double Fantasy Album

John Lennon Double Fantasy Album

John Lennon. The name itself conjures images of a revolutionary musician, a lyrical genius, and an iconoclastic Beatle. His tragic and untimely death outside The Dakota in December 1980 solidified his status as not just a rock star, but a martyr in the eyes of many. This profound loss, however, cast a long shadow, one that arguably obscured a critical look at his final studio album, Double Fantasy. Released just weeks before his assassination, this “comeback” record, intended to mark Lennon’s return from a five-year hiatus, initially faced a lukewarm reception from both critics and the public. Yet, in the aftermath of his murder, Double Fantasy was catapulted to global success, retrospectively lauded, and even Grammy-winning. But revisiting Double Fantasy today, decades removed from the emotional maelstrom of 1980, begs the question: does the album truly deserve its iconic status, or is it, as some initially argued, one of the most overrated albums in popular music history?

Context: Lennon’s Artistic Decline and “Retirement”

Before dissecting Double Fantasy, it’s crucial to acknowledge the towering musical achievements that preceded it. John Lennon’s contributions to The Beatles are legendary, shaping the landscape of popular music forever. His early post-Beatles work, including albums like John Lennon/Plastic Ono Band and Imagine, continued to showcase his brilliance and cemented his reputation as a groundbreaking solo artist. However, by the mid-1970s, a noticeable artistic slump had begun. Albums like 1974’s Walls and Bridges and 1975’s Rock ‘n’ Roll, a collection of oldies covers, signaled a creative stagnation. Rock ‘n’ Roll, often seen as the refuge of artists running dry on original ideas, inadvertently became Lennon’s last offering before he retreated from the public eye. He famously declared a hiatus from music, choosing to focus on family life and raising his son, Sean, at The Dakota apartment building in New York City. This period of “retirement” set the stage for the highly anticipated return promised by Double Fantasy.

The Initial Flop and Critical Backlash of Double Fantasy

Contrary to popular memory, Double Fantasy was not an instant hit upon its release in November 1980. Initial sales were, in fact, quite sluggish. The record-buying public, perhaps sensing a lack of urgency or innovation, didn’t rush to embrace Lennon’s comeback. More tellingly, the critical establishment, known for its discerning ear, largely met Double Fantasy with a resounding thud. Major music publications, including Rolling Stone, The Times, and The Village Voice, delivered scathing reviews, panning the album as lackluster and uninspired. This initial critical consensus is often conveniently forgotten in the album’s later narrative, yet it provides crucial context. Before the tragic events of December 1980, Double Fantasy was widely considered a creative disappointment.

The Shift After Lennon’s Murder: Hype and Grammy Win

Everything changed irrevocably with John Lennon’s murder on December 8, 1980. The outpouring of grief was global and immense. In the immediate aftermath, Double Fantasy experienced a dramatic reversal of fortune. Driven by public mourning and a desire to connect with Lennon’s final artistic statement, sales skyrocketed. Radio stations played the album incessantly, and the very critics who had initially dismissed it began to soften their stances, some even retracting their negative reviews. This wave of sentimentality culminated in Double Fantasy winning the Grammy Award for Album of the Year in 1981. While undoubtedly a tribute to Lennon’s legacy, the Grammy win, viewed through a less emotionally charged lens, feels more like a sympathetic gesture than an objective recognition of artistic merit. The question remains: did the album truly deserve this posthumous elevation, or was its success inextricably linked to the tragic circumstances of its release?

A Track-by-Track Revisit: Lennon’s Blandness vs. Ono’s Weirdness

Listening to Double Fantasy today, without the emotional weight of history, reveals a stark dichotomy between John Lennon’s contributions and those of his wife and collaborator, Yoko Ono. The album, structured as a musical dialogue between the couple, highlights a significant creative disparity.

(Just Like) Starting Over: Pedestrian Lyrics and Musical Shortcomings

The opening track, “(Just Like) Starting Over,” intended as an upbeat declaration of renewed love and life, unfortunately falls flat. Lennon’s lyrics, filled with simplistic platitudes like “Our life together is so precious together” and “It’s time for us to spread our wings and fly,” are surprisingly pedestrian for a songwriter of his caliber. The doo-wop backing vocals feel dated and uninspired, and the melody, while pleasant, lacks the spark and originality that defined Lennon’s best work. Notably absent is any significant guitar work, a surprising omission considering Lennon’s rock and roll roots and the availability of guitarists like the exceptional Earl Slick (who does appear on some of Ono’s tracks). For the man who gave us “A Day in the Life” and “The Ballad of John and Yoko,” “(Just Like) Starting Over” feels remarkably unremarkable.

Kiss Kiss Kiss (Yoko Ono): Weirdly Engaging New Wave

Following Lennon’s opener, Yoko Ono’s “Kiss Kiss Kiss” injects a jolt of unexpected energy into the album. A fast-paced New Wave dance track, it’s undeniably weird, but also strangely compelling. Ono’s unconventional vocal style, which can be generously described as ululation, is certainly not traditionally “good,” but it’s undeniably distinctive. The track features a peculiar sonic landscape, incorporating what sounds like a child’s voice morphing into orgasmic moans, all underpinned by a driving beat and, crucially, the presence of Earl Slick’s energetic guitar work. While the lyrics are undeniably simplistic, even “dumb,” they somehow work within the context of a dance track, where lyrical depth often takes a backseat to rhythm and vibe.

Cleanup Time: Vapid Lennon vs. Ono’s “No Wave Air”

“Cleanup Time,” Lennon’s subsequent track, is a limp and forgettable offering. The melody is hackneyed, and the horn arrangement feels cliché. Lyrically, Lennon fares even worse, with lines like “The queen is in the counting house / Counting out the money / The king is in the kitchen / Making bread and honey.” These lyrics, intended perhaps to depict domestic bliss, come across as tone-deaf and boastful, particularly from a multi-millionaire. In stark contrast, Ono’s bizarre musical explorations, even if jarring, offer a breath of “No Wave air” in comparison to Lennon’s vapidity.

Give Me Something (Yoko Ono): Formulaic but with Slick’s Guitar

Ono’s “Give Me Something” is another propulsive dance track, characterized by a relentless beat and somewhat irritating lyrics. The backing vocals are arguably atrocious, yet possess a strange addictive quality. Musically, the track is formulaic, driven by a repetitive bassline. The saving grace, once again, is Earl Slick’s guitar solo, a brief moment of instrumental brilliance struggling to emerge from the surrounding sonic clutter.

I’m Losing You: Lennon’s Closest to a Rocker, Psychological Insights

“I’m Losing You” represents John Lennon’s closest attempt at a rocker on Double Fantasy. While it possesses a certain energy, the melody remains unremarkable, and it hardly “rocks like a hurricane.” However, the song offers a glimpse into a more complex emotional landscape than the album’s prevalent saccharine love themes. Lennon’s lyrics hint at resentment and frustration directed towards Ono, suggesting a simmering tension beneath the surface of marital bliss. This psychological undercurrent, revealing Lennon’s dependence and underlying resentment, makes the song intriguing, despite its musical shortcomings. And, predictably, the track is redeemed by a fleeting moment of guitar brilliance from Earl Slick at its conclusion.

I’m Moving On (Yoko Ono): “I’m Losing You” Echoes and Monkey Chatter

Ono’s “I’m Moving On” bears a suspicious resemblance to “I’m Losing You,” both thematically and musically. Ono’s vocals are stilted and wooden, and the lyrics are, at best, questionable, exemplified by the line “Don’t stick your finger in my pie / You know, I’ll see through your jive.” However, the track is unexpectedly punctuated by what can only be described as “monkey chatter” at its end, a bizarre and memorable sonic flourish that arguably surpasses even Slick’s guitar work in terms of sheer memorability on Double Fantasy.

Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy): Mawkishness and a Stolen Quote

“Beautiful Boy (Darling Boy),” Lennon’s ode to his son Sean, is undeniably pretty, but also undeniably mawkish. Its unabashed sentimentality veers into saccharine territory, likely appealing primarily to parents or those with a penchant for overly sentimental ballads. The song is best remembered for the line, “Life is what happens to you while you’re busy making other plans,” which is often attributed to Lennon as a profound original insight. However, this saying predates Lennon, appearing in a 1957 issue of Reader’s Digest, diminishing its perceived profundity.

Watching the Wheels: Listenable Lennon, Irksome Lyrics

“Watching the Wheels” stands out as the most genuinely listenable Lennon track on Double Fantasy. It possesses a decent melody and a more engaging rhythm. Lennon adopts a feistier persona, though his lyrics remain somewhat irksome. The very act of releasing Double Fantasy contradicts the song’s theme of relinquishing the spotlight. Furthermore, lines like “People asking questions / Lost in confusion / Well I tell them there’s no problem / Only solutions” echo the same tone-deaf arrogance found in “Imagine”‘s “Imagine no possessions / I wonder if you can,” particularly coming from a man of immense wealth and privilege.

Yes, I’m Your Angel (Yoko Ono): Simply Bad

Yoko Ono’s “Yes, I’m Your Angel” is best left undiscussed. Suffice it to say it’s a weak song originating from what is likely an even weaker musical.

Woman: Infant-like Dependency, Not Love Song

“Woman,” perhaps one of the album’s more commercially successful tracks, suffers from the same lyrical pitfalls as much of Lennon’s Double Fantasy output. While the melody is pleasant, albeit somewhat flabby, the lyrics reveal a disturbing level of dependency rather than mature romantic love. Lines like “Woman, I hope you understand / The little child inside the man / Please remember / My life is in your hands” paint a picture of infantile dependence rather than a balanced adult relationship.

Beautiful Boys (Yoko Ono): Maudlin and Annoying Flute, but Insightful

Ono’s “Beautiful Boys,” a slow and dirge-like track dedicated to both Sean and John, is marred by Ono’s strained vocals, maudlin lyrics, and an irritating flute accompaniment. However, amidst the gloom, a moment of genuine insight emerges in the line, “And now you’re 40 years old / You got all you can carry / And still feel somehow empty.” This line subtly hints at a deeper unease and dissatisfaction beneath the surface of Lennon’s professed domestic bliss, a sentiment echoed in the Anne Leibovitz photograph depicting a naked Lennon clinging to a clothed Ono.

Dear Yoko: Perky Swill and No Slick

“Dear Yoko” is a relentlessly perky and ultimately shallow track. Played at an almost frantic pace, it feels rushed and insincere. Lennon’s lyrics once again express an almost pathological dependence on Ono, while the musical arrangement, including a particularly weak horn section, is devoid of inspiration. Notably, Earl Slick is absent, further diminishing the track’s musical appeal.

Every Man Has a Woman Who Loves Him (Yoko Ono): Funky High Art

Yoko Ono’s “Every Man Has a Woman Who Loves Him” unexpectedly emerges as the album’s high point. Despite Ono’s characteristic vocal limitations, the track boasts a genuinely funky and sinuous beat, elevating it to a surprising level of sophistication compared to Lennon’s often hackneyed melodies on the album. Earl Slick contributes tasteful guitar fills, and the rhythm section, particularly the drums, is tight and engaging. The synthesizer work adds a further layer of sonic interest, making this track a genuine standout.

Hard Times Are Over (Yoko Ono): Gospel Feel, Wrong Voice

Closing the album is Ono’s “Hard Times Are Over,” a gospel-infused track featuring organ and a hand-clapping choir. While the gospel influence is evident, the melody feels jerky and awkward. Ono’s voice, while distinctive, is ill-suited to the gospel style, and the saxophone interjections feel amateurish. The chorus is somewhat catchy, but ultimately overshadowed by Ono’s vocal limitations.

Conclusion

Charles Shaar Murray’s astute observation in his NME review of Double Fantasy hits the nail on the head: “It sounds like a great life, but it makes for a lousy record.” While Lennon may have been striving for an artistic representation of domestic contentment, Double Fantasy ultimately fails to deliver musically. The album is a fantasy, indeed, not just of a perfect marriage, but of a triumphant artistic comeback that simply didn’t materialize. While great art doesn’t necessarily demand absolute truth, Double Fantasy‘s fundamental flaw lies in its musical mediocrity. Decades later, it remains a truly bad LP, a fact often obscured by the sentimental fog of history.

GRADED ON A CURVE: D-