John Wayne, born Marion Morrison on May 26, 1907, and passing away on June 11, 1979, remains an indelible figure in American cinema. He wasn’t just an actor; he became the embodiment of the strong, silent cowboy and the unwavering soldier, personifying idealized American values for a generation. But who was John Wayne beyond the characters he portrayed on screen? This article delves into the life and career of this iconic actor, exploring his journey from Iowa to Hollywood stardom.

Marion Morrison’s story began in Winterset, Iowa, the son of a pharmacist. His childhood nickname, “Duke,” stayed with him, even appearing as Duke Morrison in early film credits. A pivotal moment came in 1925 when he enrolled at the University of Southern California. While pursuing academics and playing football for the university, Wayne took a summer job at Fox Film Corporation as a propman. This seemingly minor job placed him in the orbit of director John Ford, a friendship that would profoundly shape Wayne’s career. Ford recognized something special in the young Morrison and began casting him in small film roles starting in 1928.

Wayne’s breakthrough moment arrived in 1930 with Raoul Walsh’s The Big Trail. This film marked his first leading role and, significantly, his debut as “John Wayne.” However, the path to stardom wasn’t immediate. For the next eight years, Wayne honed his craft in over 60 low-budget films. These were formative years, primarily spent portraying cowboys, soldiers, and other rugged, adventurous characters. These roles, while not bringing immediate fame, solidified his on-screen persona and prepared him for the role that would catapult him into the cinematic stratosphere.

It was John Ford once again who provided that pivotal role. In 1939, Ford cast Wayne as the Ringo Kid in Stagecoach. This classic Western wasn’t just a film; it was a cultural phenomenon. Stagecoach established Wayne as a genuine star. The portrayal of the Ringo Kid resonated with audiences, cementing Wayne’s image as a commanding presence on screen. Following Stagecoach, Wayne’s trajectory was firmly set. Each subsequent year saw his star rise further in American cinema. Ford continued to collaborate with Wayne, directing him in The Long Voyage Home (1940). This film, based on Eugene O’Neill plays, showcased Wayne’s developing acting range and provided further evidence of his powerful screen presence, earning critical praise and solidifying his early stardom.

The onset of World War II brought a new dimension to Wayne’s on-screen image. While speculation surrounds whether Wayne intentionally avoided military service, evidence suggests his attempts to enlist in the Navy were turned down. Factors included his age, a past football injury, and a government directive prioritizing actors for morale-boosting roles. Regardless of the reasons, Wayne spent the war years contributing to the war effort in his own way: entertaining troops overseas and starring in a series of popular war films.

Movies like Flying Tigers (1942), The Fighting Seabees (1944), They Were Expendable (1945), and Back to Bataan (1945) became synonymous with John Wayne during this era. These films consistently depicted Wayne as the quintessential American fighting man, overcoming overwhelming odds with courage and determination. Beyond war films, Wayne also ventured into melodramas such as The Spoilers (1942) and Flame of Barbary Coast (1945), demonstrating his versatility. By the war’s end, John Wayne was not just a star; he was a firmly entrenched Hollywood icon, embodying American strength and resilience.

The post-war period cemented the John Wayne screen persona that endures to this day. His collaborations with John Ford and Howard Hawks during this era and into the early 1960s produced some of cinema’s most enduring classics. For Ford, Wayne starred in the acclaimed “Cavalry Trilogy”: Fort Apache (1948), She Wore a Yellow Ribbon (1949), and Rio Grande (1950). These films presented a romanticized yet complex vision of the Old West, with Wayne portraying stoic cavalry officers grappling with duty, honor, and the changing landscape of America.

Wayne’s roles in these and other Ford films offered a nuanced portrayal of the American character. He embodied unwavering patriotism, yet often displayed disillusionment with American hypocrisy. This duality is perhaps most evident in The Searchers (1956), often hailed as one of the greatest Westerns ever made. In The Searchers, Wayne’s character’s relentless pursuit to rescue his niece reveals both heroism and a disturbing, obsessive bigotry, showcasing the darker undercurrents of the Old West mythology. Ford’s exploration of these complexities culminated in The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance (1962), a film that questioned and ultimately upheld the romanticized legends of the West, even at the expense of truth. Beyond Westerns, Wayne and Ford also created standouts like The Quiet Man (1952) and Donovan’s Reef (1963), showcasing their versatile partnership.

Wayne’s collaborations with Howard Hawks, while less overtly critical, were equally significant. Red River (1948), another contender for the title of greatest Western, featured Wayne as a complex, autocratic cattle baron clashing with changing times and the values of a younger generation represented by his adopted son, played by Montgomery Clift. Their next collaboration, Rio Bravo (1959), was born from Wayne and Hawks’ dissatisfaction with High Noon. Rio Bravo presented a contrasting vision of Western heroism, with Wayne’s sheriff determined to uphold justice regardless of community support, a direct response to High Noon‘s portrayal of cowardly townsfolk. Despite initial mixed reviews, Rio Bravo has since become a classic. Hawks and Wayne revisited this narrative framework in El Dorado (1967) and Rio Lobo (1970), Hawks’ final film, further solidifying their successful partnership.

Beyond his iconic collaborations, Wayne delivered memorable performances for other directors. Sands of Iwo Jima (1949) earned him his first Oscar nomination for his portrayal of a tough Marine sergeant. Hondo (1953) stands out as a classic Western filmed in 3-D. Wayne himself directed and starred in The Alamo (1960), an epic historical drama where he played Davy Crockett. He also starred in successful World War II epics like The Longest Day (1962) and In Harm’s Way (1965). McLintock! (1963) showcased his comedic talents in a slapstick Western farce.

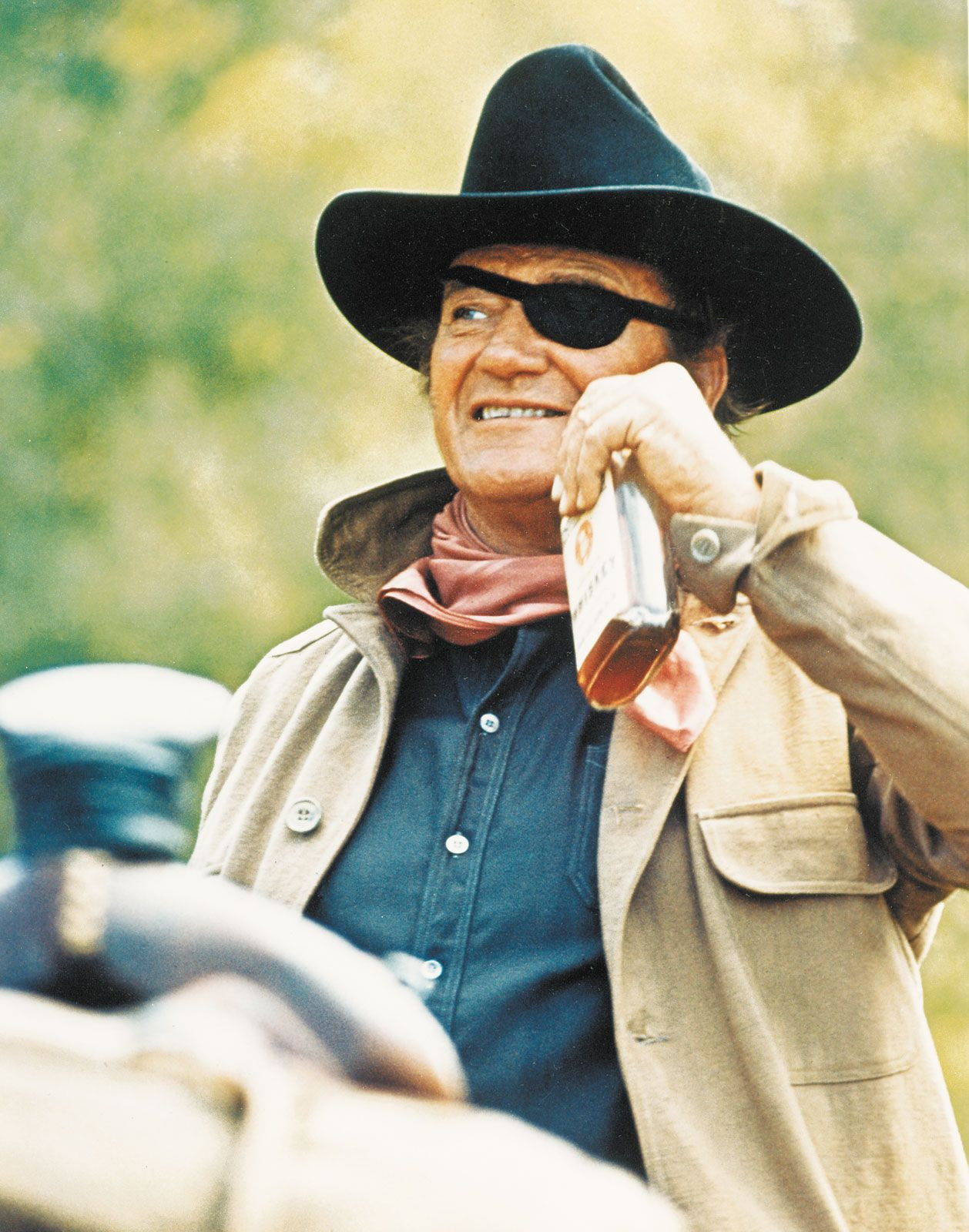

After a career spanning over four decades, John Wayne finally received an Academy Award for Best Actor for his role as the cantankerous but endearing U.S. Marshal Rooster Cogburn in True Grit (1969). He reprised this role alongside Katharine Hepburn in Rooster Cogburn (1975). Wayne’s final film, The Shootist (1976), where he portrayed an aging gunfighter dying of cancer, was lauded as one of his best Westerns since Rio Bravo and served as a poignant farewell, mirroring his own battle with the disease that would claim his life three years later.

Throughout his career, Wayne faced criticism regarding his acting range. However, his ability to convey tenderness and complexity, particularly in films like Red River and The Searchers, was often underestimated. Wayne’s outspoken conservative politics also drew controversy, admired by conservatives but criticized by liberals. Despite these controversies and criticisms, John Wayne remains a towering figure in cinematic history. He is considered a Hollywood icon and, for many, one of the greatest movie stars of all time. His legacy was further cemented with posthumous honors including the Congressional Gold Medal and the Presidential Medal of Freedom. So, Who Is John Wayne? He is more than just a movie star; he is a symbol of an era, an embodiment of American ideals, and a lasting presence in the world of film.

John Wayne in True Grit

John Wayne in True Grit