The term “Dear John letter” might sound quaint today, but it carries a significant weight of history, particularly when understanding the emotional landscape of wartime. Coined during World War II, this phrase refers to a breakup letter written by a woman to her partner, typically a soldier serving overseas. These letters, while delivering personal news, became a notable social phenomenon, reflecting anxieties about love, loyalty, and morale during periods of conflict.

The phrase “Dear John letter” surfaced in the public consciousness in October 1943, thanks to a report by Milton Bracker in The New York Times. Bracker, reporting from North Africa, highlighted “separation” as a defining aspect of wartime life. He observed the emergence of “Dear John clubs” among soldiers – informal groups formed by servicemen who had received disheartening letters from home. These letters typically began with the salutation “Dear John” and proceeded to deliver the devastating news of a girlfriend or wife finding a new romantic interest, often someone stateside and readily available. Bracker’s report captured a trend that was already being discussed in military circles and would soon become a recurring theme in wartime narratives.

Months before The New York Times article, Yank, the U.S. Army’s weekly magazine, had alluded to these letters, calling them “Brush-Off Clubs” and sharing examples without yet using the “Dear John” moniker. As the war progressed, the phrase caught on, and “Dear John letters” became a common topic in both civilian and military press. Journalists frequently cited excerpts from these archetypal letters, often portraying women’s breakup styles as ranging from the oblivious to the intentionally cruel, yet consistently relying on clichés to soften the blow – or perhaps to deliver it more effectively.

FORT BRAGG IN 1942

FORT BRAGG IN 1942

In May 1944, Howard Whitman further popularized the concept in the Chicago Daily Tribune, offering a stereotypical example of a “Dear John” letter: “Dear John: This is very hard to tell you, but I know you’ll understand. I hope we’ll always remain friends, but it’s only fair to tell you that I’ve become engaged to somebody else.” Whitman underscored the formulaic and often inadequate nature of these letters. He suggested that such predictable phrasing did little to ease the pain and, in fact, the trite sentiments could amplify the hurt caused by such delayed and impersonal news. The very format of the “Dear John letter” became synonymous with a cold and distant form of ending a relationship.

War correspondents weren’t just reporting on a trend; they often used “Dear John letters” as a platform to discuss broader themes of mail, morale, love, and loyalty. Hyperbole was often employed to emphasize the emotional impact of these letters. Whitman famously claimed, “It is doubtful if the Nazis will ever hurt them as much,” suggesting that the emotional wounds inflicted by a “Dear John letter” could be more devastating than physical injuries of war. This sentiment, while dramatic, reflected a prevailing concern about the psychological well-being of soldiers and the potential impact of negative news from home on their fighting spirit. The idea that a letter could inflict damage comparable to enemy action underscores the perceived importance of emotional support and stability for soldiers in combat.

Commentators at the time emphasized that the context of war made rejection particularly painful. A broken heart, in this view, was considered a significant, even catastrophic, injury for a soldier. Consequently, “jilted GIs” received considerable sympathy, even from military leadership. While displays of “nervousness” in combat were often stigmatized, officers sometimes showed leniency towards soldiers who reacted to romantic rejection with strong emotions like tears, depression, anger, or even aggression. This indicates a recognition, albeit perhaps limited, of the profound psychological impact of relationship breakdowns on soldiers already under immense stress.

The “Dear John” letter, in an unexpected way, provided servicemen with a rare “license to emote.” The idea that a soldier might “act out” after receiving such a letter was widely accepted in both military and civilian circles. Advice columnists like Mary Haworth in The Washington Post in July 1944, acknowledged the devastating impact of such news on male ego and morale. Haworth wrote that “bad news that strikes directly at their male ego—telling that some other man has scored with the little woman in their absence—can lay them out flat, figuratively speaking; and make them a fit candidate for hospitalization.” She argued this wasn’t a reflection of weakness but rather a demonstration of their “civilized need of special spiritual nurture” amidst the horrors of war. This perspective highlights the societal understanding, or at least acceptance, of male vulnerability in the face of romantic rejection during wartime.

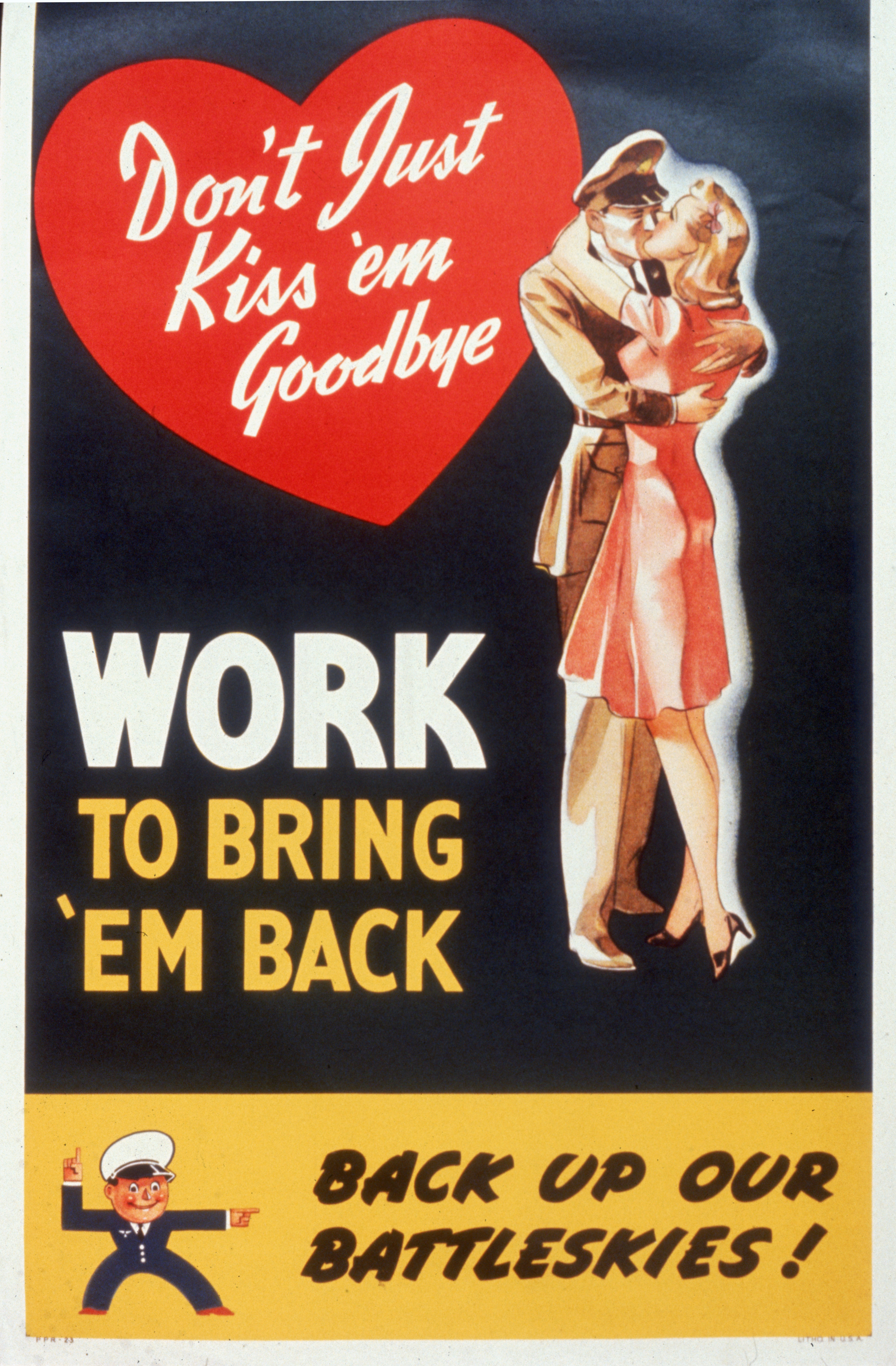

Dear John Letters Poster

Dear John Letters Poster

Echoing Haworth’s sentiments, many female opinion leaders of the time publicly condemned women who broke up with servicemen. These women were often portrayed as unpatriotic, even as “traitors,” worse than the enemy, because they were seen as undermining the morale of the troops. This rhetoric reveals the intense societal pressure on women to remain loyal and supportive to their partners fighting overseas, framing personal relationships within the larger context of national duty and wartime effort.

In the gendered dynamics of World War II, women were assigned the crucial role of maintaining the home front, which included sustaining the emotional connections with soldiers. Propaganda constantly reminded soldiers they were fighting “for home,” and women, symbolizing that home front, were expected to actively “keep the home fires burning” by writing regular, loving letters. This expectation placed a significant responsibility on women to uphold morale and emotional stability from afar.

Soldiers, facing the constant threat of death and injury, often imbued mail with an almost magical significance. Letters from home became talismans, believed to offer protection and connection to life beyond the battlefield. Some soldiers literally carried letters close to their hearts, hoping these tangible links to loved ones, and the sentiments within, could ward off harm. However, this belief in the power of mail also carried a darker side. If loving letters could protect, some soldiers feared that “Dear John letters”—unloving words—could invite misfortune or even death.

Pulitzer Prize-winning poet W.D. Snodgrass, who served as a Navy typist during WWII, recalled the palpable tension surrounding mail call. He noted the particularly somber atmosphere around any soldier who didn’t receive mail and the especially heavy sense of foreboding associated with “Dear John letters.” Snodgrass recounted a shared, perhaps superstitious, belief that “with no one to come back to, a man was less likely to come back.” This belief highlights the profound psychological impact of these letters, extending beyond personal heartbreak to encompass a perceived impact on a soldier’s very survival.

Vietnam veteran Michael McQuiston’s experience further illustrates this superstition. After receiving a “Dear John letter,” his platoon sergeant was reluctant to send him back into the field, citing a rule against it, believing it to be “bad luck.” While McQuiston insisted and subsequently was injured, his experience reinforced the ingrained superstition linking romantic rejection with negative consequences in war.

The anxiety surrounding female fidelity and its impact on soldiers’ well-being has deep historical roots, stretching back to ancient epics like Homer’s The Odyssey. The figure of Penelope, tested for her loyalty by Odysseus’s disguised return, embodies this enduring concern. While Penelope ultimately proves faithful in Homer’s version, alternative myths present her as unfaithful, highlighting a persistent cultural fascination with female disloyalty and its potential consequences for returning warriors.

“Dear John” stories, while not representing every soldier’s experience, have become a powerful and enduring trope in wartime narratives. They underscore the emotional vulnerabilities of soldiers, the societal expectations placed on women during wartime, and the enduring anxieties surrounding love and loyalty amidst the chaos of conflict. These letters, beyond their personal impact, offer a valuable lens through which to understand the social and psychological dimensions of war.

Adapted from Dear John: Love and Loyalty in Wartime America by Susan L. Carruthers.