For enthusiasts of gritty cinema, the name Lee Marvin immediately conjures a world of tough guys and morally ambiguous landscapes. Within Marvin’s iconic filmography, John Boorman’s 1967 thriller, Point Blank, consistently ranks as a standout. This neo-noir masterpiece isn’t just a personal favorite for many; it remains a touchstone in American crime cinema, a film that continues to resonate and inspire decades after its release. Having revisited Point Blank numerous times and explored its depths in writing and discussions, one might assume all facets have been uncovered. However, as recent explorations reveal, Point Blank and John Boorman’s directorial vision still hold fresh perspectives, especially when viewed through a contemporary lens.

Lee Marvin in Point Blank, a classic John Boorman film showcasing toxic masculinity and corporate alienation

Lee Marvin in Point Blank, a classic John Boorman film showcasing toxic masculinity and corporate alienation

Rediscovering Point Blank: New Perspectives on a Classic

The enduring power of Point Blank comes into sharp focus through Eric G. Wilson’s insightful BFI Film Classics monograph. This study isn’t merely a surface-level appreciation; it’s a deep dive into the film’s experimental techniques and thematic richness. Wilson’s analysis goes beyond the commonly discussed themes of toxic masculinity and corporate alienation, delving into less explored territories like gender fluidity and the film’s profound engagement with trauma and loss. For those deeply familiar with Point Blank, Wilson’s monograph offers a valuable opportunity to re-examine the film and appreciate its multifaceted nature.

One of the most compelling aspects of Wilson’s work is the connections he draws between Point Blank and a diverse range of other films. These cinematic links not only enrich our understanding of Boorman’s film but also illuminate the broader tapestry of cinematic history. While Point Blank stands alone as a powerful piece of filmmaking, exploring these connections reveals the rich cinematic conversation it engages in and contributes to. For viewers familiar with Point Blank, or those newly intrigued by John Boorman’s direction, these film recommendations provide a curated pathway to explore related cinematic landscapes.

Point Blank’s Cinematic Web: 10 Films That Deepen Your Understanding

Wilson’s monograph expertly positions Point Blank within a larger cinematic context, highlighting ten films that resonate with its themes, style, or production. Exploring these films offers a deeper appreciation for the nuances of Point Blank and its place in film history.

The Cobweb (1955)

Vincente Minnelli’s The Cobweb, a melodramatic exploration of interpersonal dynamics within a psychiatric clinic, might seem an unlikely companion to Point Blank. However, it appears fleetingly within Boorman’s film. Walker, Lee Marvin’s relentless protagonist, briefly watches The Cobweb while waiting for Brewster, the syndicate leader, at his Los Angeles residence. This brief clip offers a moment of ironic juxtaposition, highlighting the contrasting worlds of psychological turmoil in Minnelli’s film and the brutal, physical world of Point Blank.

The 400 Blows (1959)

François Truffaut’s seminal coming-of-age drama, The 400 Blows, might initially appear distant from the hard-boiled world of Point Blank. Yet, Wilson draws a compelling parallel between their endings. Both films conclude with a sense of ambiguous resolution, leaving the protagonists in a state that is both “desolate and liberated.” This shared sense of existential uncertainty connects these seemingly disparate films, suggesting a deeper thematic resonance beyond genre conventions.

Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959)

Alain Resnais’ Hiroshima Mon Amour, a poignant reflection on memory and trauma in post-war Hiroshima, finds a surprising echo in Point Blank. Wilson suggests that both films function as meditations on trauma and the subjective experience of time. Point Blank‘s fragmented narrative and Walker’s seemingly spectral presence can be interpreted as a cinematic representation of trauma’s disorienting effects, aligning it thematically with Resnais’ exploration of historical and personal wounds.

Strangers When We Meet (1960)

Richard Quine’s Strangers When We Meet, starring Kirk Douglas and Kim Novak, enters the Point Blank conversation through casting considerations. Wilson reveals that John Boorman initially considered Kim Novak for the role of Chris, eventually played by Angie Dickinson. This consideration stemmed from Novak’s performances, particularly in films like Strangers When We Meet, where she portrays a complex woman navigating illicit desires and suburban ennui. This connection highlights the potential nuances Boorman sought for the character of Chris and the film’s engagement with themes of infidelity and hidden lives.

The Americanization of Emily (1964)

Norman Jewison’s The Americanization of Emily, a cynical war romance starring James Garner and Julie Andrews, connects to Point Blank through its Director of Photography, Philip H. Lathrop. Lathrop, nominated for an Academy Award for his work on The Americanization of Emily, also served as the cinematographer for Point Blank. His innovative camerawork, including operating the camera for the legendary opening shot of Orson Welles’ Touch of Evil, significantly shaped the visual language of both films, linking them through a shared visual artistry.

The Sandpiper (1965)

Vincente Minnelli’s The Sandpiper, another mid-century melodrama featuring Elizabeth Taylor and Richard Burton, connects to Point Blank through its score composer, Johnny Mandel. Mandel, who won a Grammy for The Sandpiper score, also crafted the eerie and discordant soundtrack for Point Blank. This connection reveals a shared sensibility in using music to underscore the emotional and thematic undertones of both films, despite their vastly different genres.

Catch Us If You Can (1965)

John Boorman’s own directorial debut, Catch Us If You Can, also known as Having a Wild Weekend, offers a crucial point of reference for understanding his trajectory towards Point Blank. This Swinging Sixties film, though met with mixed reviews, brought Boorman to Hollywood’s attention, ultimately paving the way for Point Blank. Examining Catch Us If You Can provides insight into Boorman’s early stylistic inclinations and thematic interests that would later coalesce in his breakthrough neo-noir.

Grand Prix (1966)

John Frankenheimer’s high-octane racing drama, Grand Prix, connects to Point Blank through film editor Henry Berman. Fresh off an Academy Award for his editing work on Grand Prix, Berman brought his expertise to Point Blank. His editing rhythms and pacing significantly contributed to the film’s distinctive style, demonstrating how collaborations between filmmakers can shape cinematic language across genres.

The Outside Man (1972)

Jacques Deray’s The Outside Man, a French-Italian thriller set in Los Angeles, is part of a broader cinematic trend highlighted by Wilson: European directors bringing fresh perspectives to the Los Angeles crime genre. Alongside films like Jacques Demy’s Model Shop, Michelangelo Antonioni’s Zabriskie Point, and Roman Polanski’s Chinatown, The Outside Man exemplifies this outsider’s gaze. Featuring Angie Dickinson alongside Jean-Louis Trintignant and Roy Scheider, it shares cast connections with Point Blank while exploring similar themes of crime and betrayal in the sun-drenched yet shadowy landscape of LA.

The Limits of Control (2009)

Jim Jarmusch’s minimalist crime film, The Limits of Control, stands as a testament to Point Blank‘s enduring influence on subsequent crime cinema. Wilson positions Point Blank as a precursor to films like Christopher Nolan’s Memento, Nicolas Winding Refn’s Drive, and Steven Soderbergh’s The Limey, all of which bear traces of Boorman’s stylistic and thematic innovations. The Limits of Control, with its enigmatic protagonist and fragmented narrative, directly echoes Point Blank‘s exploration of alienation and fractured identity in the criminal underworld.

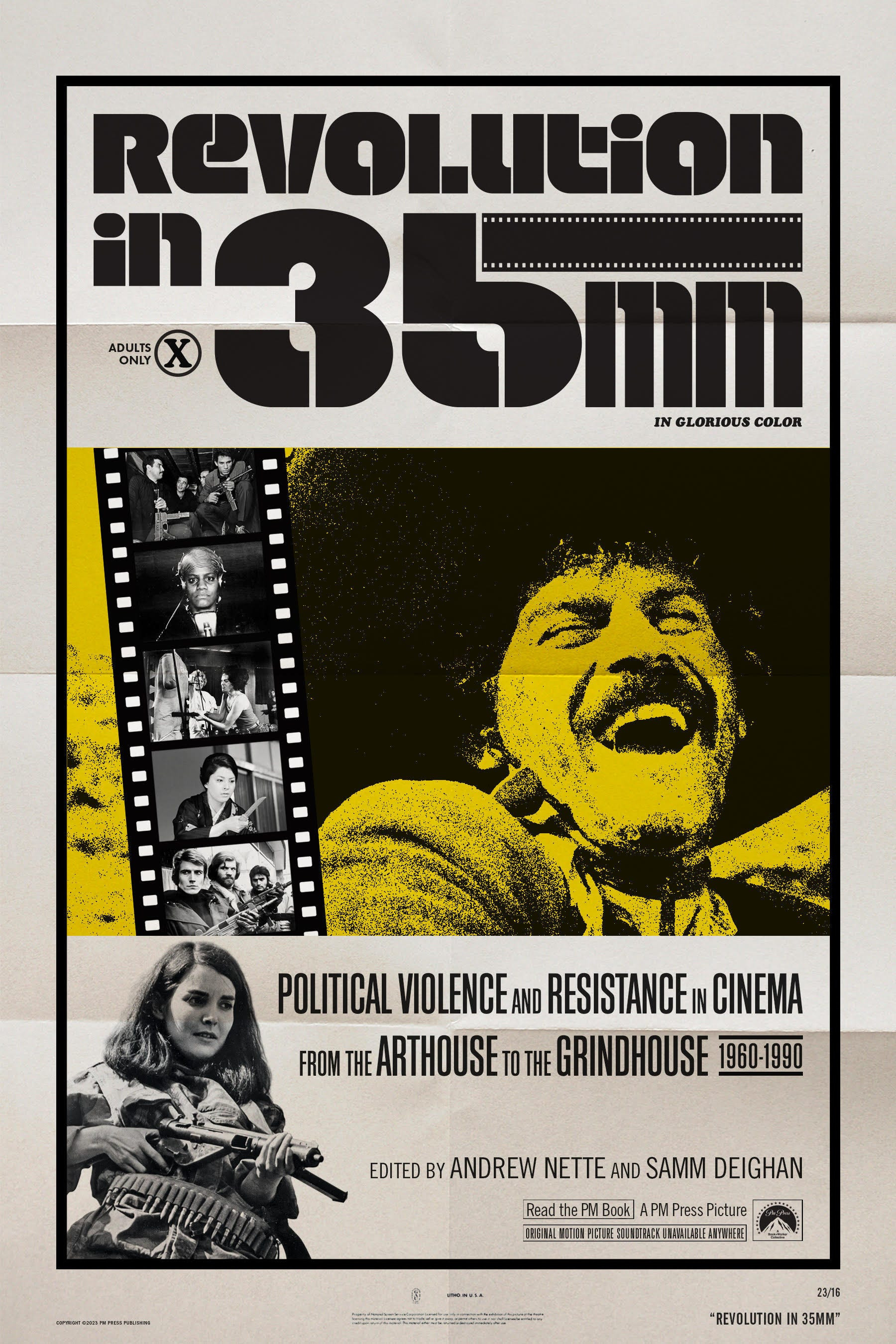

Revolution in 35mm: Political Violence and Resistance in Cinema from the Arthouse to the Grindhouse, 1960-1990

[

Book cover for Revolution in 35mm: Political Violence and Resistance in Cinema from the Arthouse to the Grindhouse, co-edited by film critic Samm Deighan and featuring exploitation film poster-style design by John Yates

Exploring these ten films in relation to Point Blank enriches not only our understanding of Boorman’s masterpiece but also the broader landscape of cinema it inhabits. Eric G. Wilson’s monograph acts as a key to unlocking these connections, prompting a renewed appreciation for Point Blank‘s artistry and lasting impact. For cinephiles and scholars alike, revisiting Point Blank through these new perspectives proves to be a rewarding cinematic journey. The film remains a powerful testament to John Boorman’s directorial prowess and its continued relevance in contemporary film discourse.

Horwitz Publications, Pulp Fiction & the Rise of the Australian Paperback

[

Paperback cover for Horwitz Publications, Pulp Fiction & the Rise of the Australian Paperback, a detailed examination of post-war Australian pulp publishing by Anthem Press.