While often overshadowed by the heroic Robin Hood and the legendary Magna Carta, Prince John remains a pivotal, if villainous, figure in the tales of Sherwood Forest. It’s easy to dismiss him as simply the greedy and petulant antagonist thwarting Robin Hood’s merry band, but his character, particularly when linked to historical narratives like the Magna Carta, reveals a more complex and enduring story. Let’s delve into the portrayal of Prince John in Robin Hood lore and his surprising connection to historical documents, inspired by an intriguing theatrical piece from the past.

Prince John, in the popular imagination, is almost synonymous with villainy. He’s the sniveling, power-hungry younger brother of King Richard the Lionheart, left in charge of England and immediately abusing his position. Stories paint him as tyrannical, imposing unjust taxes, and relentlessly pursuing Robin Hood for daring to stand up to his corruption. This depiction, solidified in countless books, films, and television series, casts Prince John as the embodiment of everything Robin Hood fights against: oppression, greed, and the abuse of power. He’s the perfect foil to Robin Hood’s righteous outlaw, creating a classic good versus evil dynamic that has captivated audiences for centuries.

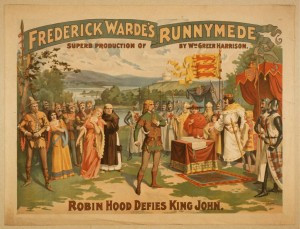

A color poster advertising the play Runnymede featuring Frederick Warde as Robin Hood.

A color poster advertising the play Runnymede featuring Frederick Warde as Robin Hood.

This image is from a promotional poster for “Runnymede,” a play that intertwines Robin Hood’s legend with the Magna Carta, featuring Frederick Warde as Robin Hood.

Interestingly, this villainous portrayal of Prince John even found its way into theatrical interpretations that attempted to bridge the gap between Robin Hood’s fictional world and real historical events. Consider “Runnymede,” a play written by William Greer Harrison around 120 years ago. This play, as highlighted in a Library of Congress blog post, takes significant liberties with history to weave Robin Hood into the narrative surrounding the Magna Carta. Set during the reign of King Richard, the play depicts Prince John as regent, mismanaging England while Richard is away on crusade. Robin Hood and his men, portrayed as opposing John’s usurpation and tyranny, become a thorn in the prince’s side by robbing from the rich and giving to the poor, disrupting John’s tax collection.

The play escalates the conflict by introducing a love triangle: Prince John desires Maid Marian, but she is in love with Robin Hood. This personal affront fuels John’s desire to eliminate Robin Hood. The plot thickens with Richard’s return and subsequent murder by John, who then seizes the throne, solidifying his villainous role. However, in a dramatic turn inspired by historical events, the barons of England rise against King John, not to save Robin Hood directly, but to address John’s overall misrule. They capture him and famously force him to sign the Magna Carta.

The play “Runnymede” culminates in a scene where the signing of Magna Carta becomes the pivotal moment that saves Robin Hood’s life. The play emphasizes the significance of Chapter 39 of Magna Carta, which guarantees due process and protection against arbitrary imprisonment, suggesting that this landmark document directly prevents Prince John from unjustly executing Robin Hood. In this theatrical interpretation, Magna Carta itself becomes the hero, rescuing the outlaw from the clutches of the tyrannical Prince John.

Black and white photograph of Bohemian Club members camping in a forest.

Black and white photograph of Bohemian Club members camping in a forest.

This photo shows members of the Bohemian Club, to which playwright William Greer Harrison belonged, camping in a sylvan setting, reflecting the romanticism of nature often associated with Robin Hood tales.

While “Runnymede” received mixed reviews for its historical inaccuracies and dramatic quality, it underscores a fascinating cultural trend: the desire to connect the Robin Hood legend with significant historical moments like the creation of Magna Carta. Historically, King John, the real Prince John, was indeed known for his unpopular rule and was compelled to agree to Magna Carta by his barons in 1215. However, the notion that this charter directly saved a figure like Robin Hood is a romanticized embellishment. Robin Hood himself is likely a composite or entirely fictional figure, and Magna Carta’s immediate impact was more about limiting royal power in general than protecting specific outlaws.

Despite the historical liberties taken, the enduring appeal of stories linking Prince John, Robin Hood, and Magna Carta lies in their symbolic power. Prince John represents tyranny and injustice, Robin Hood embodies resistance against oppression, and Magna Carta symbolizes the rule of law and the protection of individual liberties. Even if historically inaccurate, the narrative of Magna Carta saving Robin Hood from Prince John resonates because it encapsulates the core themes of these enduring legends: the fight for justice against tyranny. As we consider the legacy of both Robin Hood and Magna Carta, understanding the role of Prince John, even as a villain, helps us appreciate the rich tapestry of history, legend, and the ongoing human struggle for fairness and freedom.