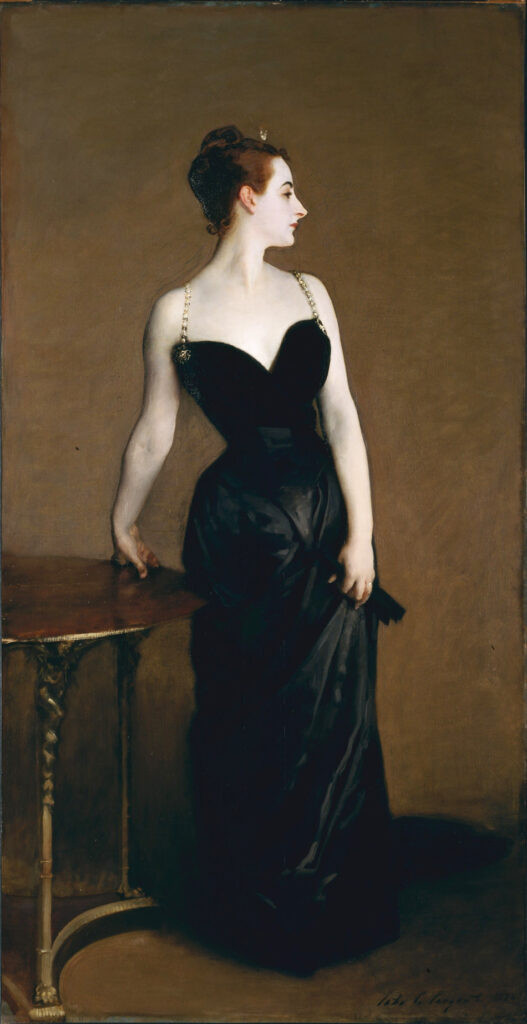

John Singer Sargent’s Madame X has captivated art enthusiasts for over a century. This striking portrait of Madame Pierre Gautreau, a prominent figure in Parisian society, transcends a mere likeness, delving into the complexities of personality and the intriguing interplay of opposing forces within an individual. Through the lens of Aesthetic Realism, we can explore how Sargent masterfully portrays the dynamic between “assertion” and “retreat” in Madame X, reflecting a universal dichotomy present in us all.

Madame X, John Singer Sargent, 1884. Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Madame X, John Singer Sargent, 1884. Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

The Aesthetic Opposites in Sargent’s Portraiture

Aesthetic Realism, founded by the philosopher Eli Siegel, proposes that beauty in art arises from the “making one of opposites.” This principle resonates deeply with Sargent’s Madame X. Siegel himself articulated fifteen pairs of opposing qualities inherent in women, one of which, “Advancing: Recessive,” is particularly pertinent to understanding this portrait. He described this duality as:

“Towards something is in the feminine mind importantly: the future as outward and to be visited and had. But how much retreat is in woman, too, the unseen sinking, the leaving for a previously chosen background.”

Madame X serves as a compelling visual study of these intertwined opposites, qualities that are not exclusive to women but are universally human. Sargent, through his artistic genius, captures this intricate balance on canvas.

Scandal and Shifting Perceptions

When Madame X debuted at the Paris Salon of 1884, it ignited a scandal. The portrait’s perceived boldness and unconventional portrayal of Madame Gautreau shocked Parisian society. Sargent was compelled to withdraw the painting amidst the uproar. However, years later, in 1916, when selling the painting to the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Sargent declared, “I suppose it is the best thing I have done.” He also requested the title be changed to Madame X.

This title change itself is significant. Madame X is both more assertive and enigmatic than Portrait of Madame Pierre Gautreau. It amplifies the dramatic essence of the work while simultaneously shrouding the subject in mystery. By impersonalizing the title, Sargent elevates the portrait beyond a specific individual, allowing it to represent the very concept of “woman,” or perhaps, the universal human condition itself, marked by internal contrasts.

Personal Resonance: Assertion and Retreat Within

The author’s personal experience studying Aesthetic Realism and Eli Siegel’s teachings adds a layer of depth to the analysis of Madame X. Siegel’s insightful questions, such as “Do you believe you have a fight between showing off and retreating?” resonated deeply, revealing a personal struggle with these very opposites. This internal conflict – the desire to be noticed and admired juxtaposed with a simultaneous urge to withdraw and remain aloof – mirrors the dynamic captured in Sargent’s portrait.

This internal tension, described as “contempt” in Aesthetic Realism – wanting a grand impact while simultaneously retreating from genuine engagement with the world – is a source of discomfort and pain. Madame X, in this context, becomes a powerful representation of how assertion and retreat can be harmoniously, even beautifully, integrated. Art, driven by a purpose to honestly perceive and represent the world, can guide individuals towards integrating these opposing forces within themselves.

Sargent’s Broader Exploration of Opposites

Eli Siegel further illuminated Sargent’s artistic focus on these opposing qualities in a lesson where he discussed Sargent’s portrayal of women. He asked, “Do you believe that a self is a oneness of the greatest outwardness and the greatest inwardness?” He pointed to Sargent’s portraits of women from the early 20th century, noting their blend of demureness and self-expression.

Here are examples of Sargent’s portraits that showcase this duality:

Lady Agnew of Lochnaw, John Singer Sargent, 1892-93

Lady Agnew of Lochnaw, John Singer Sargent, 1892-93

Mrs. Louis Raphael, John Singer Sargent, 1905-06

Mrs. Louis Raphael, John Singer Sargent, 1905-06

These portraits, alongside Madame X, illustrate Sargent’s recurring interest in capturing the nuanced interplay between outward presentation and inner life, assertiveness and demureness, in his subjects.

Decoding Madame X: A Symphony of Contrasts

One of the most striking aspects of Madame X is the stark contrast between black and white. The expanse of pale skin – the forehead, neck, shoulders, and arms – exudes a sense of assertion and display. Conversely, the black satin dress, while bold, also possesses a depth, a mystery, a sense of receding. The surrounding brown tones further complicate this interplay, offering a muted backdrop that is not purely recessive but rich with both “glow and shadow.”

Madame Gautreau herself was a figure of contrasts. A celebrated beauty known for her lavender powder and meticulous attention to appearance, she was described as having a “studied, indifferent, statuesque presence” that commanded attention. However, this carefully constructed persona was also fragile. An anecdote recounts how an overheard comment about her appearing “worn” led to her complete withdrawal from public life, retreating into darkened rooms, devoid of mirrors.

This dramatic withdrawal underscores the vulnerability beneath the assertive facade. Just as Sargent captures the visual opposites in his painting, Madame Gautreau embodied the personal struggle between projecting an image of confidence and succumbing to insecurity and retreat. Eli Siegel’s questions, “Do you think there can be an accuracy in going forward and retreating—of being ourselves from within and also showing ourselves?…Do you think everything can be done with a oneness of advance and retreat?” speak directly to this human dilemma. The challenge, and the potential beauty, lies in “showing off gracefully,” in finding a harmonious balance between assertion and retreat.

The Posing Puzzle: Finding the Balance

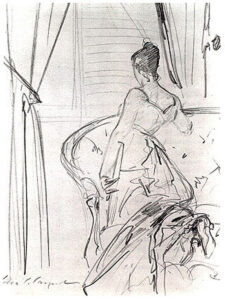

Sargent’s journey to find the perfect pose for Madame X was extensive, reflecting his dedication to capturing this balance of opposites. Numerous sketches reveal his exploration of various positions:

Study for Madame X, sketch 1, John Singer Sargent

Study for Madame X, sketch 1, John Singer Sargent

Studies for Madame X, sketches, John Singer Sargent

Studies for Madame X, sketches, John Singer Sargent

Study for Madame X, front-on couch, John Singer Sargent

Study for Madame X, front-on couch, John Singer Sargent

Oil study for Madame X (Madame Gautreau Drinking a Toast), John Singer Sargent

Oil study for Madame X (Madame Gautreau Drinking a Toast), John Singer Sargent

Study for Madame X, back view, John Singer Sargent

Study for Madame X, back view, John Singer Sargent

Ultimately, Sargent settled on a pose where Madame Gautreau stands beside an Empire table, her body facing forward while her head is turned in profile.

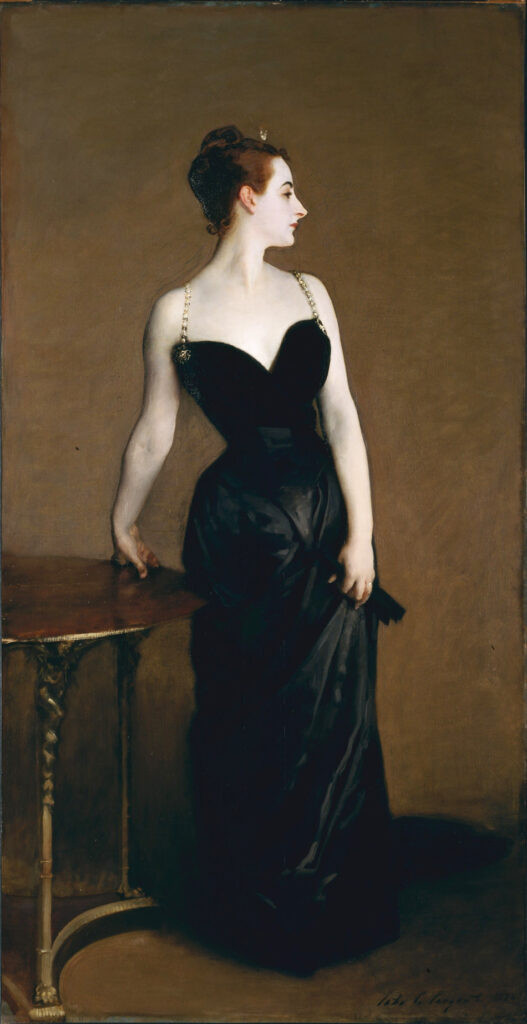

Madame X, John Singer Sargent, 1884. Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Madame X, John Singer Sargent, 1884. Oil on canvas. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

This chosen pose is itself a brilliant embodiment of assertion and retreat. The body’s forward stance is confident and assertive, while the head in profile is partially hidden, more contemplative. As Siegel noted, “The profile of a person is the more intellectual part because the angle seems to stand more for thought.” In Madame X, Sargent masterfully merges physicality and intellect, outward presentation and inner thought.

Detail of Madame X's head, John Singer Sargent

Detail of Madame X's head, John Singer Sargent

A Portrait of Wholeness: Admiration, Criticism, and Comprehension

Madame X‘s enduring power lies in Sargent’s comprehensive approach to his subject. The portrait is not simply celebratory or critical; it is an attempt to present Madame Gautreau in her entirety, encompassing admiration, criticism, and profound comprehension. Details like the subtly pink ear suggest attentiveness, a willingness to listen and yield. The warm tones highlighting her eyes, nose, mouth, and hands emphasize her connection to the world, the very means through which she perceives and engages with reality.

Even the abstract element of space within the painting contributes to this theme of opposing forces. The space between Madame Gautreau’s arm and dress mirrors the form of her nose – projecting outward and receding inward – further reinforcing the visual motif of assertion and retreat. The sharp delineation of her left side contrasts with the softer, receding contours of her right arm, creating a dynamic interplay of forward and backward motion, display and withdrawal. Her dependence on the table, while appearing assertive, also reveals a need for support, for connection to the external world.

The table itself echoes these opposing forces. Its curves and straight lines, its light and shadow, its solid presence and receding planes, mirror the complexities within Madame Gautreau. The visual rhymes between the table and Madame Gautreau – the curve of the table base echoing the hem of her dress, the mahogany tones of her hair mirroring the table’s wood, the table leg’s twist reflecting the gentle curve of her arm – all contribute to a unified composition where woman and object are inextricably linked, both embodying the dance of assertion and retreat.

Finding Graceful Assertion Through Connection

The presence of the table is crucial. It enhances our understanding of Madame Gautreau, adding depth and power to her portrayal. This suggests a profound insight: to truly and gracefully assert oneself, one must acknowledge and embrace one’s need for the world, for connection and engagement with what is outside oneself. Aesthetic Realism, with its emphasis on seeing the world as truly beautiful and valuable, provides a framework for understanding and achieving this graceful assertion, a balance of opposites that is both personally fulfilling and aesthetically compelling, as embodied in Sargent’s unforgettable Madame X.

Related Articles:

Matisse’s The Blue Window; or, The Self Is Both Inside & Outside by Barbara McClung

Is Art Really & Urgently About Life?: The Drawings of Leonardo da Vinci by Marcia Rackow

*Power and Tenderness in Men and in Picasso’s Minotauromachy by Chaim Koppelman