During a summer trip, an unexpected upgrade led to a stay in the John Singer Sargent Suite at the Inn on the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina, setting the stage for an immersive encounter with the artistry of John Singer Sargent. The visit was perfectly timed with a planned tour of the Vanderbilt Estate the following day, little did I know about the deep connection between the Vanderbilts and Sargent’s masterpieces.

View from the John Singer Sargent Suite at Biltmore Estate, showcasing the distant Vanderbilt mansion amidst lush greenery.

View from the John Singer Sargent Suite at Biltmore Estate, showcasing the distant Vanderbilt mansion amidst lush greenery.

It turns out, George Vanderbilt, the visionary behind the Biltmore Estate, was one of John Singer Sargent’s most significant American patrons. This revelation was surprising yet logical, considering Sargent’s talent for cultivating relationships with wealthy elites who readily commissioned his sought-after portraits. The allure of witnessing these John Singer Sargent Paintings in their original context, within the opulent Vanderbilt mansion nestled in the scenic North Carolina mountains, was undeniable.

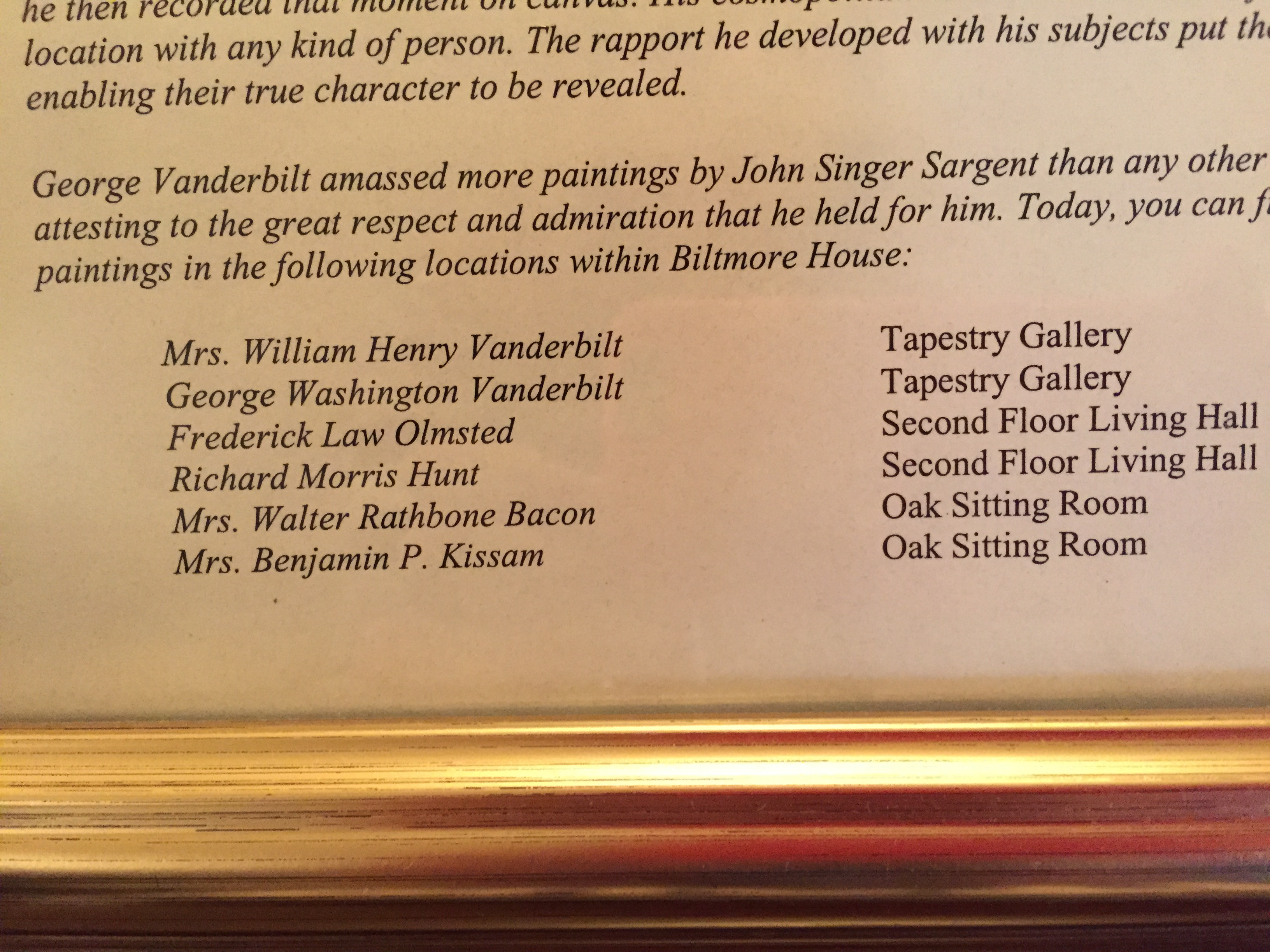

Intrigued by the economics of art patronage in the Gilded Age, I attempted to uncover the commission fees for a Sargent portrait during the peak of his career in the late 1880s and 1890s. While anecdotal sources suggested figures around $100,000 per commission, the reliability of this information remained uncertain, especially in terms of present-day value. Regardless of the exact sum, George Vanderbilt’s patronage, evidenced by multiple portraits of family and associates, clearly indicated his financial capacity and deep appreciation for Sargent’s talent. A thoughtful detail within the Sargent Suite was a framed information sheet, meticulously outlining the John Singer Sargent paintings to be found within the Biltmore Estate and their precise locations within the mansion.

Framed informational sheet in the John Singer Sargent Suite listing Sargent paintings on display at the Biltmore Estate.

Framed informational sheet in the John Singer Sargent Suite listing Sargent paintings on display at the Biltmore Estate.

The sheer grandeur of the Biltmore Estate is breathtaking, almost overwhelming in its lavishness. Its extravagance can feel detached from contemporary life, like stepping into a bygone era of unparalleled opulence. The estate evokes the grandeur of a European castle, an unexpected sight in the American landscape. Yet, amidst this overwhelming luxury, the John Singer Sargent portraits of the Vanderbilt family brought a sense of human presence and intimacy to the monumental estate. These paintings served as a reminder that real people, albeit extraordinarily wealthy ones, once inhabited and shaped this magnificent place. During the Biltmore tour, I found myself drawn back to the rooms housing the Sargent paintings, spending considerably more time admiring them than in any other part of the house.

Ornate interior of the Biltmore Estate, showcasing lavish furnishings and architectural details.

Ornate interior of the Biltmore Estate, showcasing lavish furnishings and architectural details.

Intricate architectural detail of the Biltmore Estate, highlighting the craftsmanship and scale of the mansion.

Intricate architectural detail of the Biltmore Estate, highlighting the craftsmanship and scale of the mansion.

Another view of the Biltmore Estate interior, emphasizing the opulent decor and historical ambiance.

Another view of the Biltmore Estate interior, emphasizing the opulent decor and historical ambiance.

Close-up of the Biltmore Estate's detailed interior, showing rich textures and elaborate design elements.

Close-up of the Biltmore Estate's detailed interior, showing rich textures and elaborate design elements.

Photography is restricted inside the Biltmore Estate to preserve its delicate interiors and the visitor experience, but thankfully, public domain images allow us to appreciate the John Singer Sargent paintings on display.

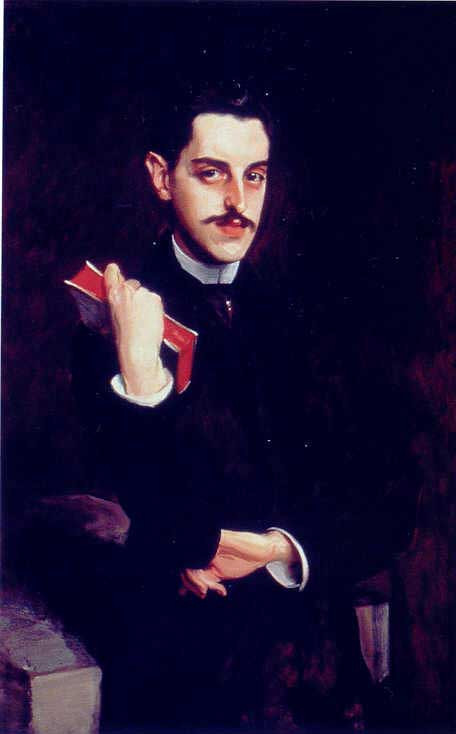

John Singer Sargent's portrait of George W. Vanderbilt, depicting him as a contemplative intellectual with a vividly red book.

John Singer Sargent's portrait of George W. Vanderbilt, depicting him as a contemplative intellectual with a vividly red book.

The Portrait of George W. Vanderbilt (1890) immediately captivates with its unexpected portrayal. The striking crimson pages of the book Vanderbilt holds are a bold focal point, echoed subtly in the subject’s lips and the delicate shading around his eyes. Sargent masterfully captures Vanderbilt not as a robust industrialist, but as a refined, youthful intellectual, his well-manicured hands suggesting a life removed from manual labor. Indeed, George Vanderbilt, grandson of the shipping magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, harbored little interest in the family business. His passions lay in the arts, philanthropy, and the meticulous creation of the Biltmore Estate itself. He remained unmarried until the age of forty, eight years after this portrait was painted, fueling persistent rumors about his sexuality, despite his later marriage and fatherhood.

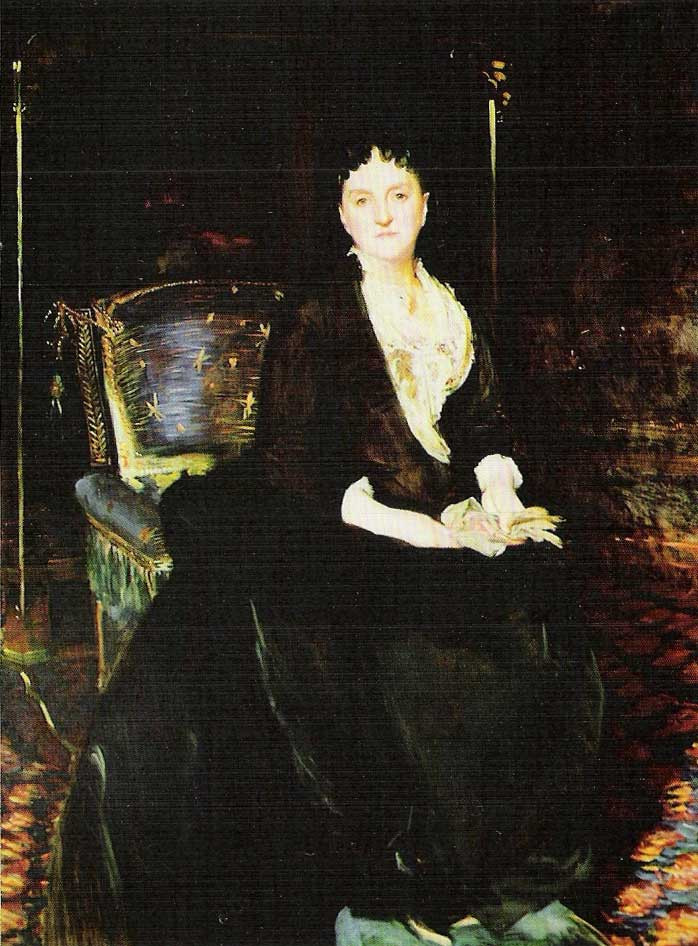

John Singer Sargent's portrait of Mrs. William Henry Vanderbilt, portraying her as an imposing matriarch in rich attire.

John Singer Sargent's portrait of Mrs. William Henry Vanderbilt, portraying her as an imposing matriarch in rich attire.

In contrast, the Portrait of Mrs. William Henry Vanderbilt (1888), George’s mother Maria Louisa Kissam, presents a figure of formidable matriarchal presence. Painted before the construction of Biltmore began, this John Singer Sargent painting captures the essence of the Vanderbilt dynasty’s preceding generation, embodying power and social stature.

John Singer Sargent's portrait of Mrs. Walter Rathbone Bacon, capturing her lively personality and fashionable attire.

John Singer Sargent's portrait of Mrs. Walter Rathbone Bacon, capturing her lively personality and fashionable attire.

The Portrait of Mrs. Walter Rathbone Bacon (1896) depicts Virginia Purdy Bacon, George Vanderbilt’s cousin, radiating a vivacious and engaging personality. Raised in Bordeaux, she married an American railroad magnate and divided her time between Europe and New York. A patron of the arts and an art dealer herself, Virginia Bacon is particularly notable for being painted by both John Singer Sargent and Anders Zorn. Famously, the two artists engaged in a friendly rivalry to see who could best capture her likeness, with Sargent reportedly conceding that Zorn’s portrayal was superior. Zorn’s portrait of Mrs. Bacon can be viewed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, offering an interesting point of comparison to Sargent’s interpretation.

John Singer Sargent's portrait of Mrs. Benjamin Kissam, depicting her with elegance and poise characteristic of the era.

John Singer Sargent's portrait of Mrs. Benjamin Kissam, depicting her with elegance and poise characteristic of the era.

Mrs. Benjamin Kissam (1888), George’s aunt, provides another fascinating glimpse into the Vanderbilt family circle. Comparing the portraits of Mrs. Kissam and Mrs. William Henry Vanderbilt with those of George and Virginia Bacon reveals a subtle yet perceptible shift in the depiction of the Vanderbilt generations, reflecting evolving social norms and individual personalities within the family.

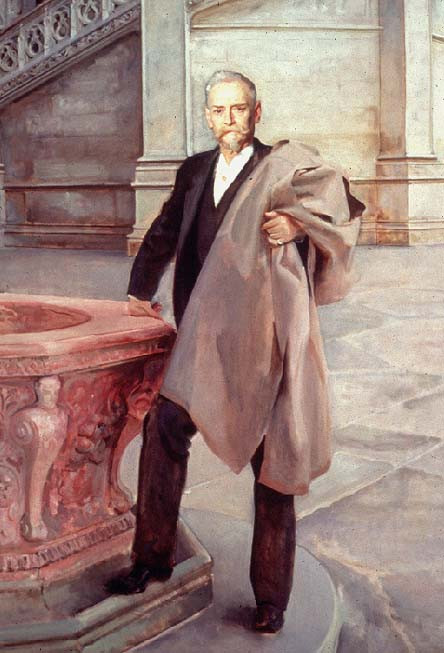

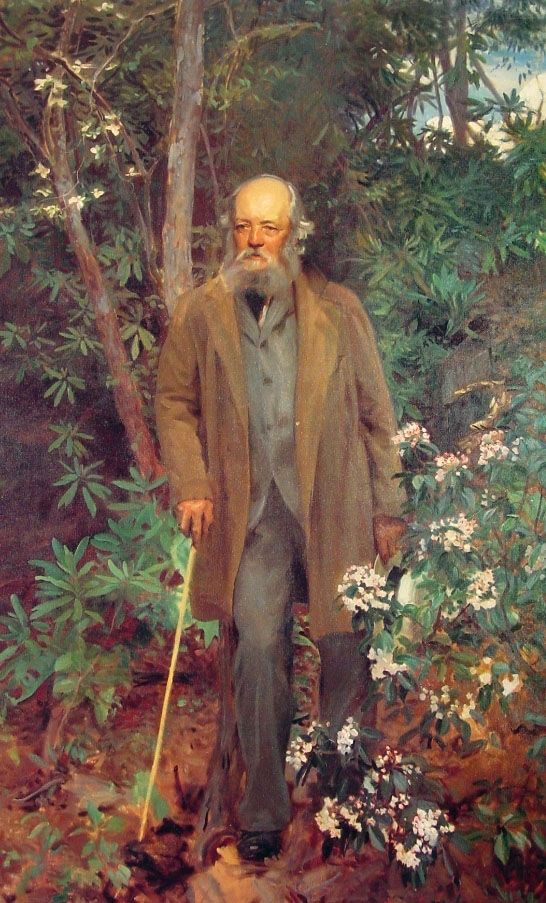

Beyond family portraits, George Vanderbilt also commissioned John Singer Sargent to paint portraits of Richard Morris Hunt and Frederick Law Olmsted, the principal architect and landscape designer of Biltmore, respectively. These portraits are prominently displayed in the Second Floor Hall of Biltmore Estate, acknowledging their crucial roles in creating this American landmark.

John Singer Sargent's portrait of Richard Morris Hunt, capturing the architect's professional demeanor and intellect.

John Singer Sargent's portrait of Richard Morris Hunt, capturing the architect's professional demeanor and intellect.

John Singer Sargent's portrait of Frederick Law Olmsted, portraying the landscape architect in a thoughtful and dignified manner.

John Singer Sargent's portrait of Frederick Law Olmsted, portraying the landscape architect in a thoughtful and dignified manner.

Surprisingly, amidst this collection of Sargent masterpieces, it was a portrait by Giovanni Boldini that resonated most deeply. While Boldini’s style can sometimes be perceived as overly flamboyant, his portrait of George Vanderbilt’s young wife, Edith Stuyvesant Dresser, struck a perfect balance. Edith, who married George in 1898 and shared a relatively brief marriage of sixteen years before George’s untimely death in 1914, must have possessed a remarkable charisma, vividly captured by Boldini’s brush.

Giovanni Boldini’s Mrs. George Vanderbilt (1911) is a dazzling display of virtuoso brushwork and captures Edith Vanderbilt’s evident flair and captivating presence. It’s easy to imagine that Edith herself was delighted with this striking and dynamic portrayal.

Further Exploration:

- John Singer Sargent Gallery, George W. Vanderbilt’s Biltmore: JSSgallery.org – An online resource dedicated to John Singer Sargent’s works, featuring a section on the Biltmore portraits.

- The Biltmore Blog: A Fashionable Lady, Cornelia Vanderbilt’s Wedding – Official Biltmore Estate blog with articles providing historical context and insights into the Vanderbilt family.

- Anders Zorn’s Portrait of Mrs. Walter Bacon: Explore the portrait by Sargent’s rival at the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s online collection by searching “Anders Zorn Mrs. Walter Bacon” on Metmuseum.org.

- John Singer Sargent and Madame X: [Link to a relevant blog post about Sargent and Madame X] – For those interested in further exploring Sargent’s Parisian period and iconic works, offering a broader view of his artistic journey. (Note: Since the original link is to a WordPress.com blog, and the instructions discourage external links generally, it’s best to omit this or replace it with a link to a reputable art history site if deemed crucial).