Stepping into the Tate Britain’s exhibition, Sargent and Fashion, one is immediately immersed in a world of undeniable technical brilliance. The galleries are filled with portraits by John Singer Sargent, the American artist whose very name rolls off the tongue with a melodious elegance. Yet, amidst the dazzling brushstrokes and shimmering fabrics, a question lingers: do these portraits offer genuine depth, or are they merely beautiful surfaces, devoid of soul?

The exhibition, as observed by a fellow critic, prompts a moment of self-reflection. Standing before these towering figures of high society, one can’t help but feel like a “scuttling sewer rat” in comparison. Sargent’s subjects, predominantly women, are presented as paragons of beauty and grace, meticulously crafted to please and flatter. These were the elite of their time, the nouveau riche and aristocracy who could afford Sargent’s sought-after brush. His studio, located in the fashionable Tite Street, Chelsea, placed him at the heart of London’s high society, even across the street from Oscar Wilde, further cementing his place within these exclusive circles.

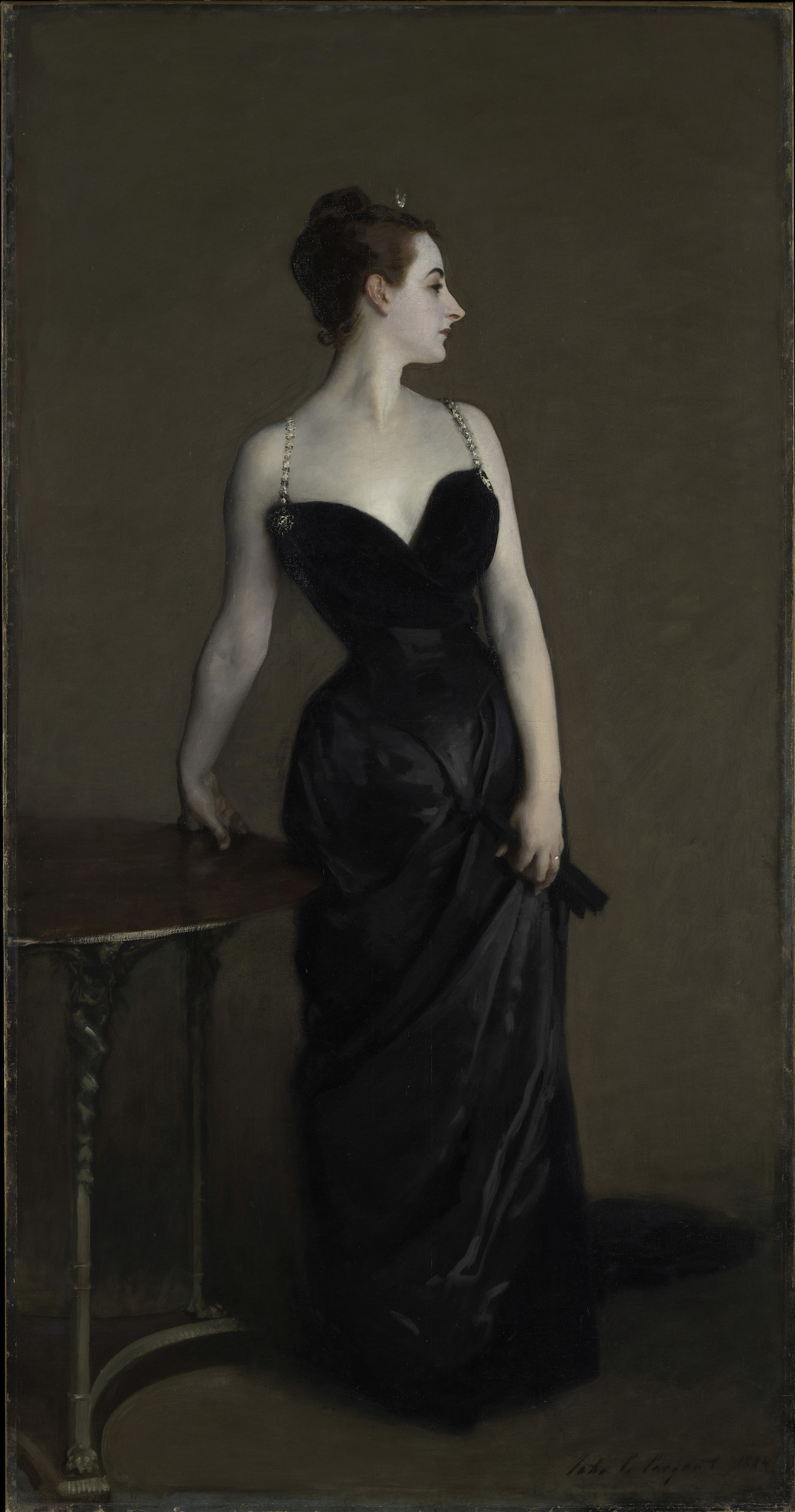

John Singer Sargent, “Madame X” (1883–84), oil paint on canvas; The Metropolitan Museum of Art (© The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence; all images courtesy Tate)

John Singer Sargent, “Madame X” (1883–84), oil paint on canvas; The Metropolitan Museum of Art (© The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence; all images courtesy Tate)

Sargent’s Snobbery and Social Divide

However, beneath the veneer of glamour, a hint of disdain surfaces when considering Sargent’s attitude towards those outside his gilded world. Recalling a visit to Sheffield’s Weston Park Museum, home to a Sargent portrait of the Vickers sisters, daughters of a local industrialist, reveals a less flattering side of the artist.

Sargent’s letters expose a clear contempt for painting subjects from a different social stratum. Anticipating the Sheffield commission in 1884, he wrote of painting “three ugly young women of Sheffield, dingy hole,” revealing a snobbishness jarringly at odds with the polished elegance of his society portraits. Were these women truly “uglier” than his usual clientele, or was his perception colored by their non-aristocratic background? This anecdote raises questions about the artist’s empathy and the sincerity of his portrayals.

John Singer Sargent, “Lady Helen Vincent, Viscountess d’Abernon” (1904), oil paint on canvas; Collection of the Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama

John Singer Sargent, “Lady Helen Vincent, Viscountess d’Abernon” (1904), oil paint on canvas; Collection of the Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama

The Art of Fashionable Posing

As a sought-after John Singer Sargent portraitist, certain elements consistently preoccupied him. Firstly, the presentation of the sitter within the canvas frame – the carefully constructed pose, whether reclining languidly on a chaise lounge or standing rigidly with a cane, dictated by the subject’s persona and the desired impression. Secondly, the drapery – the opulent fabrics that swathed his subjects, often serving practical purposes like concealing pregnancies, but always contributing to the overall spectacle. The exhibition thoughtfully displays some of these original garments alongside their painted representations, allowing for direct comparison and highlighting Sargent’s meticulous attention to detail in rendering textures and folds.

Installation view of *Sargent and Fashion* at Tate Britain picturing “La Carmencita” (c. 1890) and her costume (c. 1890) (photo by Jai Monaghan © Tate)

Installation view of *Sargent and Fashion* at Tate Britain picturing “La Carmencita” (c. 1890) and her costume (c. 1890) (photo by Jai Monaghan © Tate)

Ultimately, the face remained paramount. Sargent aimed to capture the “winning look,” the sitter’s yearning for eternal beauty and admiration. This focus on idealized representation, while technically impressive, sometimes overshadows any deeper emotional or psychological exploration.

The Curious Case of Sargent’s Hands

A recurring weakness in John Singer Sargent‘s otherwise masterful technique is his depiction of hands. Often, they appear disproportionate – porcine, stubby, or excessively long, with poorly defined fingers, sometimes even appearing abruptly truncated. Did Sargent simply overlook the anatomical intricacies of the hand, or was it a deliberate artistic choice, or perhaps a lack of interest?

Examining the right hand of “Madame X” (Virginie Gautreau) reveals a particularly egregious example. The hand is rendered with a disconcerting abruptness, described as “hideous butchery.” This same “butchery” is, according to the original critic, repeated in the hands of one of the “ugly young women” from Sheffield, suggesting a possible correlation between Sargent’s perceived social standing of his subjects and the care he took in portraying them. Whether intentional or not, these flawed hands become a point of unease within the otherwise flawless surfaces of his portraits.

John Singer Sargent, “Portrait of Miss Elsie Palmer (A Lady in White)” (1889–90), oil paint on canvas; Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center

John Singer Sargent, “Portrait of Miss Elsie Palmer (A Lady in White)” (1889–90), oil paint on canvas; Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center

John Singer Sargent, “Mrs. Hugh Hammersley” (1892), oil paint on canvas; The Metropolitan Museum of Art (© The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence)

John Singer Sargent, “Mrs. Hugh Hammersley” (1892), oil paint on canvas; The Metropolitan Museum of Art (© The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence)

John Singer Sargent, “Mrs- Carl Meyer and her Children” (1896), oil paint on canvas; Tate (photo © Tate)

John Singer Sargent, “Mrs- Carl Meyer and her Children” (1896), oil paint on canvas; Tate (photo © Tate)

John Singer Sargent, “Portrait of Ena Wertheimer: A Vele Gonfie” (1904), oil paint on canvas; Tate (photo by Oliver Cowling © Tate)

John Singer Sargent, “Portrait of Ena Wertheimer: A Vele Gonfie” (1904), oil paint on canvas; Tate (photo by Oliver Cowling © Tate)

Conclusion: Sargent’s Enduring Legacy

The Sargent and Fashion exhibition at Tate Britain provides a compelling opportunity to re-evaluate John Singer Sargent‘s oeuvre. While his technical prowess is undeniable, and his portraits offer a fascinating glimpse into the fashion and society of his time, questions about depth and empathy persist. Are these portraits merely dazzling displays of skill and superficial beauty, or do they offer something more profound? The exhibition leaves viewers to grapple with this question, prompting a nuanced appreciation of Sargent’s complex and often contradictory artistic legacy within the realm of fashionable portraiture.

[Sargent and Fashion continues at Tate Britain (Millbank, London, England) through July 7. The exhibition was curated by James Finch, with Assistant Curator Chiedza Mhondoro. A curator’s tour and exhibition talk will take place on March 15.]