John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, a name synonymous with fantasy literature, stands as a towering figure in 20th-century literature. More than just the creator of beloved classics like The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien was a distinguished scholar of the English language, a philologist of immense depth, and a storyteller whose invented world of Middle-earth continues to captivate millions across the globe. This exploration delves into the biographical tapestry of John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, uncovering the influences, experiences, and intellectual pursuits that shaped the man and his enduring literary legacy.

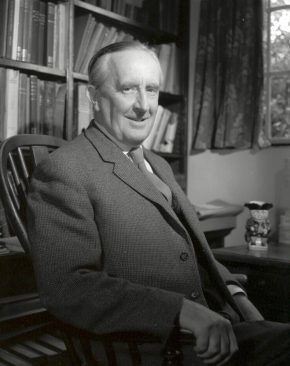

Photo by Pamela Chandler. © Diana Willson. Used with permission.

Photo by Pamela Chandler. © Diana Willson. Used with permission.

J.R.R. Tolkien in a contemplative pose, image captures the essence of the author known for his profound literary creations.

Born in 1892 and passing away in 1973, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s life spanned a period of immense historical and cultural change. He held the prestigious position of Professor of Anglo-Saxon at the University of Oxford not once, but twice, a testament to his scholarly expertise in Old and Middle English. While academia formed a significant part of his life, it is his fictional works that have cemented his place in popular culture. The Hobbit, published in 1937, and the epic saga of The Lord of the Rings, released between 1954 and 1955, transported readers to Middle-earth, a meticulously crafted pre-historic realm. This world, populated by humans, elves, dwarves, and a host of fantastical creatures like orcs and hobbits, resonated deeply with readers, fostering a devoted global readership. Despite some initial skepticism from the traditional literary establishment, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s works found fervent appreciation amongst readers, particularly gaining traction with the counter-culture movement of the 1960s due to their underlying environmental themes. By 1997, public polls in Britain affirmed his enduring popularity, ranking his works among the greatest books of the 20th century. It’s important to note the correct spelling: Tolkien, without the common misspelling “Tolkein.”

Formative Years: Childhood and Youth of J.R.R. Tolkien

The surname “Tolkien,” pronounced with equal emphasis on both syllables as Tol-keen, was believed by the family, including John Ronald Reuel Tolkien himself, to have German roots. They associated it with “Toll-kühn,” meaning foolishly brave or stupidly clever – which is why he sometimes used the pseudonym “Oxymore.” However, linguistic research suggests a possible Baltic origin, perhaps from “Tolkyn” or “Tolkīn.” Regardless of its precise etymology, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s paternal lineage traces back to his great-great-grandfather, John Benjamin Tolkien, who emigrated from Gdańsk (then part of Prussia) to Britain around 1772 with his brother Daniel. They rapidly assimilated into English society. John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s father, Arthur Reuel Tolkien, considered himself thoroughly English. Arthur, a bank clerk, sought better career opportunities in South Africa in the 1890s. His fiancée, Mabel Suffield, from a family deeply rooted in the West Midlands of England, joined him there. John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, known as Ronald to his family and early friends, was born in Bloemfontein, South Africa, on January 3, 1892. His early memories of Africa, though fragmented, were vivid, including a memorable, slightly frightening encounter with a large spider, an image some believe subtly influenced his later writings. However, this period was short-lived. On February 15, 1896, his father passed away, prompting Mabel to return to England with Ronald and his younger brother Hilary, settling in the West Midlands.

The West Midlands of John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s childhood presented a stark contrast between the burgeoning industrial landscape of Birmingham and the quintessential English countryside of Worcestershire and the surrounding Severn Valley. This region, the birthplace of composers like Elgar, Vaughan Williams, and Gurney, and close to the land of poet A.E. Housman, shaped young Tolkien’s sensibilities. His life was divided between these two worlds: the then-rural hamlet of Sarehole, south of Birmingham, with its iconic mill, and the increasingly urban Birmingham, where he attended King Edward’s School. The family later moved to King’s Heath, where their house backed onto a railway line. The young and linguistically inclined Ronald was fascinated by the coal trucks passing to and from South Wales, bearing place names like “Nantyglo,” “Penrhiwceiber,” and “Senghenydd,” sparking his imaginative engagement with language and place. Later, they relocated to the more affluent Birmingham suburb of Edgbaston.

A significant turning point for the family occurred in 1900 when Mabel and her sister May converted to Roman Catholicism. This decision estranged them from parts of their extended family. From that point forward, both Ronald and Hilary were raised in the Catholic faith, remaining devout throughout their lives. Father Francis Morgan, a parish priest of Welsh and Spanish descent, became a regular visitor and a key figure in their lives. The Tolkiens lived a modest, genteel life, but their financial situation worsened considerably in 1904 when Mabel was diagnosed with diabetes, a fatal illness in the pre-insulin era. She died on November 14, 1904, leaving Ronald and Hilary orphaned and in precarious circumstances. Father Francis stepped in, ensuring their material and spiritual well-being. In the short term, the boys were boarded with an unsympathetic aunt, Beatrice Suffield, and subsequently with a Mrs. Faulkner.

Even at a young age, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien displayed remarkable linguistic talents. He excelled in Latin and Greek, the cornerstones of classical education, and demonstrated aptitude for numerous other languages, both modern and ancient, notably Gothic and later, Finnish. He indulged his linguistic curiosity by creating his own languages purely for personal enjoyment. At King Edward’s School, he formed close friendships. In his later school years, these friends, including Robert Gilson, Geoffrey Bache Smith, and Christopher Wiseman, formed a group known as the “T.C.B.S.” – Tea Club, Barrovian Society, named after their meeting place, the Barrow Stores. They maintained close correspondence, sharing and critiquing each other’s literary endeavors until 1916.

Another significant personal development occurred during his time at Mrs. Faulkner’s boarding house. Among the lodgers was Edith Bratt, a young woman three years his senior. A friendship blossomed between Ronald, then 16, and Edith, aged 19, gradually evolving into a deeper affection. Father Francis intervened, forbidding Ronald from seeing or even communicating with Edith until he reached the age of 21. John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, with remarkable discipline, adhered strictly to this directive. In the summer of 1911, he joined a walking tour in Switzerland, an experience that may have inspired his descriptions of the Misty Mountains and Rivendell in his later works. In the autumn of 1911, he matriculated at Exeter College, Oxford. There, he immersed himself in Classics, Old English, Germanic languages (especially Gothic), Welsh, and Finnish. In 1913, upon turning 21, he promptly reconnected with Edith. He achieved a second-class degree in Honour Moderations, the intermediate stage of Oxford’s four-year Classics program, although he earned an “alpha plus” in philology. This result led him to switch from Classics to English Language and Literature, a field more aligned with his passions. During his Old English studies, he encountered Cynewulf’s poem Crist, and was particularly struck by the cryptic couplet:

Eálá Earendel engla beorhtast

Ofer middangeard monnum sended

This translates to:

Hail Earendel, brightest of angels,

over Middle-earth sent to men.

(“Middangeard” was the Old English term for the mortal realm, situated between Heaven and Hell.)

This ancient verse profoundly inspired John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, sparking early attempts to create a world of ancient beauty in his own poetic endeavors. In the summer of 1913, he took a tutoring position in Dinard, France, escorting two Mexican boys. The job ended tragically, through no fault of his, reinforcing his apparent aversion to France and French culture. Meanwhile, his relationship with Edith progressed smoothly. She converted to Catholicism and moved to Warwick, whose castle and surrounding countryside deeply impressed Ronald. As their bond strengthened, international tensions escalated, culminating in the outbreak of World War I in August 1914.

War, Lost Tales, and the Path to Academia for John Ronald Reuel Tolkien

Unlike many of his contemporaries, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien did not immediately rush to enlist at the war’s onset. He returned to Oxford, dedicating himself to his studies, and earned a first-class degree in June 1915. During this period, he continued to develop his poetic works and invented languages, particularly Qenya (later spelled Quenya), heavily influenced by Finnish. However, he still sought a unifying thread to connect his burgeoning imaginative concepts. John Ronald Reuel Tolkien finally enlisted as a second lieutenant in the Lancashire Fusiliers, while simultaneously developing ideas around Earendel the Mariner, who transforms into a star, and his voyages. He spent months in England, primarily in Staffordshire, awaiting deployment, a period filled with “boring suspense.” As deployment to France seemed imminent, he and Edith married in Warwick on March 22, 1916.

He was eventually sent to the Western Front, arriving just in time for the Somme Offensive. After four months of intense combat in and out of the trenches, he contracted “trench fever,” a typhus-like infection prevalent in the unsanitary conditions. In early November 1916, he was sent back to England and spent a month recovering in a Birmingham hospital. By Christmas, he had recuperated enough to join Edith at Great Haywood in Staffordshire. Tragically, during these months, all but one of his close friends from the T.C.B.S. had perished in action. Partly as a tribute to their memory, and profoundly affected by his war experiences, he began to formalize his stories, writing “… in huts full of blasphemy and smut, or by candle light in bell-tents, even some down in dugouts under shell fire” [Letters 66]. This creative outpouring evolved into The Book of Lost Tales (published posthumously), the earliest iteration of the Silmarillion narratives. These tales featured the Elves and the “Gnomes” (Deep Elves, later the Noldor), with their languages Qenya and Goldogrin. The Book of Lost Tales contained early versions of the wars against Morgoth, the siege and fall of Gondolin and Nargothrond, and the stories of Túrin and Beren and Lúthien.

Throughout 1917 and 1918, recurring illness hampered him, but periods of remission allowed him to perform home service at various camps, earning him a promotion to lieutenant. While stationed near Hull, he and Edith walked in the woods at Roos, where, in a grove thick with hemlock, Edith danced for him. This poignant moment became the inspiration for the tale of Beren and Lúthien, a recurring and deeply personal narrative within his Legendarium. He came to see Edith as his Lúthien and himself as Beren. Their first son, John Francis Reuel (later Father John Tolkien), was born on November 16, 1917.

Following the Armistice on November 11, 1918, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien began seeking academic employment. By the time of his demobilization, he had secured a position as Assistant Lexicographer on the New English Dictionary (the Oxford English Dictionary), then under compilation. While engaged in meticulous philological work, he also shared one of his Lost Tales publicly. He read The Fall of Gondolin to the Exeter College Essay Club, receiving positive feedback from an audience that included future “Inklings” Neville Coghill and Hugo Dyson. However, his tenure at the dictionary was brief. In the summer of 1920, he applied for and, to his surprise, was appointed to the senior post of Reader (Associate Professor equivalent) in English Language at the University of Leeds.

At Leeds, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien not only taught but also collaborated with E.V. Gordon on the renowned edition of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. He continued to refine The Book of Lost Tales and his invented Elvish languages. He and Gordon also established a “Viking Club” for undergraduates, focused on reading Old Norse sagas and enjoying beer. For this club, they created Songs for the Philologists, a collection of traditional songs and original verses translated into Old English, Old Norse, and Gothic, set to traditional English melodies. Leeds also witnessed the birth of two more sons: Michael Hilary Reuel in October 1920 and Christopher Reuel in 1924. In 1925, the Rawlinson and Bosworth Professorship of Anglo-Saxon at Oxford became vacant. John Ronald Reuel Tolkien applied and was successful, marking his return to Oxford.

Professor Tolkien, The Inklings, and the Genesis of Hobbits

Returning to Oxford as a Professor was, in many ways, a homecoming for John Ronald Reuel Tolkien. While he harbored no illusions about academia as an idyllic haven, he was temperamentally suited to the scholarly life – teaching, research, intellectual exchange, and occasional publication. His academic publication record was, in fact, relatively sparse, a point of potential criticism in today’s performance-driven academic environment.

However, his scholarly outputs, though infrequent, were highly influential. His lecture “Beowulf: The Monsters and the Critics” significantly reshaped Beowulf scholarship. His insightful, often seemingly offhand, comments frequently transformed the understanding of specific fields. For example, his essay “English and Welsh” illuminated the origins of the term “Welsh” and explored phonaesthetics (both essays are collected in The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays). His academic life was otherwise largely conventional. In 1945, he transitioned to the Merton Professorship of English Language and Literature, a position he held until his retirement in 1959. Beyond his scholarly work, he taught undergraduates and participated in university administration.

His family life remained equally grounded. Edith gave birth to their fourth child and only daughter, Priscilla, in 1929. John Ronald Reuel Tolkien developed the tradition of writing illustrated letters to his children annually, purportedly from Father Christmas, a selection of which was published posthumously as The Father Christmas Letters in 1976. He also regaled them with numerous bedtime stories, which would later contribute to his literary output. In adulthood, John entered the priesthood, while Michael and Christopher both served in the Royal Air Force during the war. Michael became a schoolmaster, Christopher a university lecturer, and Priscilla a social worker. The family lived quietly in North Oxford, later Ronald and Edith moved to Headington, a suburb of Oxford.

However, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s social life was far from ordinary. He became a founding member of the Inklings, an informal literary group of Oxford intellectuals and writers. The name “Inklings” was chosen for its punning association with writing and its vaguely Anglo-Saxon sound; it did not imply any claim to divine insight. Prominent members included Neville Coghill, Hugo Dyson, Owen Barfield, Charles Williams, and most importantly, C.S. Lewis, who became one of John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s closest friends and whose conversion back to Christianity was significantly influenced by Tolkien. The Inklings met regularly for conversation, drinks, and readings of their works in progress.

The Storyteller Emerges: From Bedtime Tales to The Hobbit

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien continued to develop his mythology and languages alongside his academic pursuits and social engagements. He told his children stories, some of which were later published posthumously as Mr. Bliss and Roverandom. According to his own account, the spark for The Hobbit arose unexpectedly. While grading examination papers – a task he found profoundly tedious – he discovered a blank page in an answer book. On this page, seemingly driven by a whimsical impulse, he wrote: “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.”

Intrigued by this spontaneous sentence, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien decided to explore what a hobbit was, its dwelling, and its motivations. This exploration blossomed into a tale he initially told to his younger children and later circulated among friends. In 1936, an incomplete typescript reached Susan Dagnall, an employee at the publishing firm George Allen & Unwin (now part of HarperCollins).

Dagnall urged John Ronald Reuel Tolkien to complete the story and presented the finished manuscript to Stanley Unwin, the firm’s chairman. Unwin, in turn, had his ten-year-old son Rayner read it and provide a report. Rayner’s enthusiastic response led to the publication of The Hobbit in 1937. It was an immediate success, becoming a fixture on children’s recommended reading lists ever since. Its popularity prompted Stanley Unwin to inquire if John Ronald Reuel Tolkien had any similar material.

By this time, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien had been working on his Legendarium, aiming to present it in a more publishable form. He noted that hints of this mythology had already subtly permeated The Hobbit. He was then calling the overarching narrative Quenta Silmarillion, or Silmarillion for short. He submitted some of his “completed” tales to Unwin, who sought reader feedback. The reader’s report was mixed, praising the prose but disliking the poetry (the submitted material was the story of Beren and Lúthien). The overall conclusion at the time was that The Silmarillion was not commercially viable. Unwin tactfully conveyed this to John Ronald Reuel Tolkien but inquired if he would consider writing a sequel to The Hobbit. Disappointed by the initial rejection of The Silmarillion, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien agreed to take on the challenge of “The New Hobbit.”

This “sequel” rapidly evolved into something far grander than a children’s story. The sixteen-year saga of its creation, culminating in The Lord of the Rings, is a complex story in itself. Rayner Unwin, now an adult, played a crucial role in the later stages of this project, skillfully managing a famously meticulous and sometimes dilatory author who, at one point, considered offering the entire work to a rival publisher (who quickly retreated when the scale of the project became clear). It is largely thanks to Rayner Unwin’s advocacy that The Lord of the Rings was published at all. His father’s firm, anticipating a potential loss of £1,000 but hoping for succès d’estime, decided to publish it under the title The Lord of the Rings in three volumes during 1954 and 1955. US rights were sold to Houghton Mifflin. It soon became evident that both author and publishers had vastly underestimated the work’s popular appeal.

The Rise of a “Cult” Following for John Ronald Reuel Tolkien

The Lord of the Rings quickly captured public attention. Reviews were polarized, ranging from ecstatic praise (from W.H. Auden and C.S. Lewis) to harsh criticism (from Edmund Wilson, Edwin Muir, and Philip Toynbee), with a wide spectrum of opinions in between. The BBC produced a heavily condensed 12-episode radio adaptation on the Third Programme, the BBC’s “intellectual” channel in an era when radio still dominated media. Far from incurring losses, sales soared, leading John Ronald Reuel Tolkien to jokingly regret not having retired earlier to enjoy the financial benefits. However, this initial success was based solely on hardback sales.

The true phenomenon began with the unauthorized paperback edition of The Lord of the Rings in 1965. This paperback release made the book accessible to a much wider audience, placing it in the realm of impulse purchases. Furthermore, the ensuing copyright dispute generated significant publicity, alerting millions of American readers to a work that was unlike anything they had previously encountered, yet seemed to resonate deeply with their zeitgeist. By 1968, The Lord of the Rings had become almost a touchstone for the burgeoning “Alternative Society.”

This development evoked mixed feelings in John Ronald Reuel Tolkien. On one hand, he was immensely flattered and, to his surprise, became quite wealthy. On the other hand, he deplored the association of his work with drug culture, particularly the notion of experiencing The Lord of the Rings under the influence of LSD. Arthur C. Clarke and Stanley Kubrick faced similar reactions to 2001: A Space Odyssey. Fan interactions became increasingly intrusive. Some fans would arrive at his house to gawk, while others, especially from California, would call at 7 p.m. their time (3 a.m. in the UK) demanding answers to obscure lore questions, such as Frodo’s success or failure, Quenya verb conjugations, or the presence or absence of Balrog wings. To regain privacy, he changed addresses, had his phone number unlisted, and eventually relocated with Edith to Bournemouth, a genteel South Coast resort (Hardy’s “Sandbourne”), known for its large elderly, affluent population.

Meanwhile, the “cult” of John Ronald Reuel Tolkien and the fantasy genre he had, if not invented, then certainly revitalized (much to his bewilderment), was truly taking off – a phenomenon that warrants its own separate exploration.

Beyond Middle-earth: Scholarly and Other Writings of John Ronald Reuel Tolkien

Despite the overwhelming attention focused on The Lord of the Rings, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien maintained a steady output of other writings between 1925 and his death. These included numerous scholarly essays, many collected in The Monsters and the Critics and Other Essays; Middle-earth related works like The Adventures of Tom Bombadil; editions and translations of Middle English texts such as Ancrene Wisse, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, Sir Orfeo, and The Pearl; and stories independent of the Legendarium, such as Imram, The Homecoming of Beorhtnoth Beorhthelm’s Son, The Lay of Aotrou and Itroun, and notably, Farmer Giles of Ham, Leaf by Niggle, and Smith of Wootton Major.

The flow of publications continued even after John Ronald Reuel Tolkien’s death. The Silmarillion, edited by his son Christopher Tolkien, was finally published in 1977. In 1980, Christopher also released Unfinished Tales of Númenor and Middle-earth, a collection of his father’s incomplete later writings. In the introduction to Unfinished Tales, Christopher alluded to The Book of Lost Tales, describing it as “itself a very substantial work, of the utmost interest to one concerned with the origins of Middle-earth, but requiring to be presented in a lengthy and complex study, if at all” (Unfinished Tales, p. 6, paragraph 1).

The commercial success of The Silmarillion surprised George Allen & Unwin, and Unfinished Tales was even more successful. Recognizing a market for even more specialized Tolkien material, they embarked on the “lengthy and complex study” of The Book of Lost Tales. This project expanded far beyond initial expectations, resulting in the twelve-volume History of Middle-earth, edited by Christopher Tolkien, a surprisingly successful publishing endeavor. (Tolkien’s publishers underwent several mergers and name changes between the project’s inception in 1983 and the paperback publication of Volume 12, The Peoples of Middle-earth, in 1997.) Over time, further posthumous publications emerged, including Roverandom (1998), The Children of Húrin (2007), Beowulf: A Translation and Commentary (2014), Beren and Lúthien (2017), and most recently The Fall of Gondolin (2018), further enriching the vast Tolkien corpus.

Finis: The Enduring Legacy of John Ronald Reuel Tolkien

After retiring in 1959, Edith and Ronald moved to Bournemouth. Edith passed away on November 29, 1971. Shortly after, John Ronald Reuel Tolkien returned to Oxford, residing in rooms provided by Merton College. He died on September 2, 1973. He and Edith are buried together in the Catholic section of Wolvercote Cemetery in Oxford’s northern suburbs. (The grave is clearly marked from the cemetery entrance.) Their headstone bears the inscription:

Edith Mary Tolkien, Lúthien, 1889–1971

John Ronald Reuel Tolkien, Beren, 1892–1973

Last Updated 05/02/2024

Further Reading on John Ronald Reuel Tolkien

J.R.R. Tolkien Timeline. The Tolkien Society. Online, 2014.

Tolkien: A Biography. Humphrey Carpenter. Allen and Unwin, London, 1977.

Letters of J.R.R. Tolkien. Ed. Humphrey Carpenter with Christopher Tolkien. George Allen and Unwin, London, 1981.

The Tolkien Family Album. John Tolkien and Priscilla Tolkien. HarperCollins, London, 1992.

Tolkien and the Great War. John Garth. HarperCollins, London, 2002.

Tolkien at Exeter College. John Garth. Exeter College, Oxford, 2014.

“On J.R.R. Tolkien’s Roots in Gdańsk“. Ryszard Derdzinski. 2017.

“Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel (1892–1973).” T. A. Shippey. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press. Print 2004. Online 2006. (Also available as a podcast.)

The J.R.R. Tolkien Companion and Guide. Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull. 2nd edn. HarperCollins, London, 2017. 3 vols.