In a courtroom filled with anticipation and the weight of decades, an elderly Bill McCabe, aged 85, summoned every last bit of his strength to reach the witness stand. It was January 2013, and after 43 years, the trial he had long awaited was finally beginning. For Bill McCabe, this day was about more than just a trial; it was about his son, John Mccabe.

Prosecutor: Good morning, Mr. McCabe … do you remember September 27th 1969?

Bill McCabe: Yes, sir.

Prosecutor: How old was John at that day?

Bill McCabe: He was 15 years, six months and two weeks.

Evelyn McCabe, John’s mother, had always envisioned a bright future for her son, John Joseph McCabe. “I always visualized him as being a big shot somewhere. John Joseph McCabe. ‘My son, JJ,’ you know?” she shared with “48 Hours” correspondent Richard Schlesinger. “But I never got to see any of those things.” The vibrant dreams she held for John were tragically cut short in the autumn of 1969, a time marked by both monumental achievements, like the moon landing and Woodstock, and unspeakable loss for the McCabe family in Tewksbury, Massachusetts.

“I think we have a right to be proud of him,” Bill McCabe stated, his voice resonating with a father’s enduring love.

McCabe family portrait from 1969

McCabe family portrait from 1969

The summer of 1969 was the last the McCabe family would spend together in complete joy. John’s father, Bill, was an engineer, and his mother, Evelyn, was a school librarian. His sisters, Roberta, then 6, and Debbie, 17, fondly remembered their brother as an energetic and curious teenager, always engaged in typical brotherly antics.

Debbie chuckled as she recalled, “It was pretty interesting. You open the closet door, and your closet’s filled with grasshoppers.” Roberta added, “I just remember his hands were always dirty, like, with oil or grease or a frog in his hand.” Evelyn chimed in, “He brought home a goose once too? Oh yeah, Canadian goose, big sucka!” Her eyes sparkled with the warmth of cherished memories as Schlesinger observed, “It’s fun to watch you talk about this cause your eyes light up. I mean you have fond memories of those days.” “Oh yeah,” Evelyn replied, her voice filled with a mix of joy and sorrow.

Evelyn treasured every memento of her son, John McCabe. “I have John’s money,” Evelyn said, revealing a poignant detail. “I — I can’t spend it.” Schlesinger asked, “And you’ve had it all these years?” “Yeah, 45 years,” Evelyn confirmed. “Do you take it out a lot?” “Every now — every now and then I — the smell’s gone off of it now,” she chuckled, bringing the cash to her nose. “I almost put it in the casket with him. And then I thought, ‘No, I’ll just keep it with me. And when I see him again, I’ll give it to him.'”

The last time Evelyn saw John McCabe was on September 26, 1969. She had given him permission to attend a dance at the Knights of Columbus Hall. “Took a shower, scrubbed his hair, put his father’s aftershave on. He didn’t shave but he put his father’s aftershave on. Oh yeah, he got all spruced up,” Evelyn reminisced. However, that night carries a weight of regret. “I let him go. I let him go out the door. I shouldn’t have,” she lamented.

As the hours passed, Evelyn’s anxiety grew. “Eleven o’clock, I started looking out the window,” Evelyn recounted. “That’s when the dance closes. He should be home by midnight. So I went down to the dance and checked the road, screaming out the window. John! John! …No John. … I started prayin’ at that point.” The following day brought the devastating news no parent ever wants to hear. Police arrived at their home and took Evelyn’s husband to the basement, away from her, to deliver the horrifying truth. “They didn’t want me to know anything,” she said. “But I heard them.”

Driven by a mother’s intuition and dread, Evelyn knelt by a bathroom vent, straining to hear the muffled conversation from the basement below. “This is where I could hear everything that was going on down cellar,” she explained, kneeling on the bathroom floor, recreating that agonizing moment from years ago.

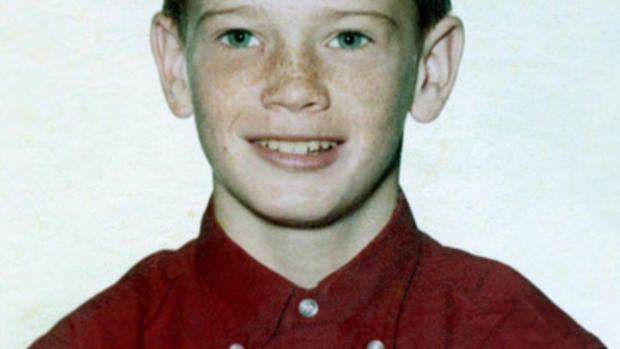

Police officer speaking to boys who found John McCabe

Police officer speaking to boys who found John McCabe

Through the vent, Evelyn overheard the chilling details. The police informed her husband that John McCabe’s body had been found by three young boys in a vacant lot in Lowell, a neighboring city known for its rough edges. “I heard that he was tied up. And there was tape on his eyes, on his mouth. I heard a lot,” Evelyn told Schlesinger, her voice breaking with the memory. “I cried. I lay there and cried.”

The Initial Investigation and False Leads in the John McCabe Case

The discovery of John McCabe sparked a massive investigation involving the Lowell, Tewksbury, and Massachusetts State Police. Gerry Leone, who later became the local District Attorney and took on the cold case, described the initial evidence collected. “The rope that was used to tie John up … Tape that was used to tape his eyes and mouth. All of his clothing and his shoes,” Leone detailed. “There was forensic evidence, but it wasn’t really meaningful because you couldn’t tie it to anyone in particular.”

Rope found at the John McCabe crime scene

Rope found at the John McCabe crime scene

Early in the investigation, a witness reported seeing a car near the crime scene on the night of John McCabe’s disappearance. “And I believe the way he had described it was a 1965 Chevy Impala, colored — plum or maroon,” Leone stated. This car description became a significant clue in the initial phase of the investigation into the death of John McCabe.

Another lead emerged when police were directed to Mike Ferreira, a 16-year-old schoolmate of John McCabe. Ferreira claimed he barely knew John. “I probably seen him like a handful of times in my life. I didn’t really — he wasn’t a friend,” Ferreira stated. Ferreira and his friend, Nancy Williams, were questioned because they admitted to picking up John McCabe hitchhiking on his way to the dance. “I picked him up and gave him a ride to the corner and I never saw him again,” Williams recounted.

Ferreira told police that after dropping off John McCabe, he rejoined Nancy Williams and later met up with his best friend, Walter Shelley. “Me, Walter and Bob Ryan took a ride to Lowell tryin’ to get some beer,” he explained. They were driving Walter Shelley’s car, which was a maroon 1965 Chevy Impala, matching the description from the witness. Police searched Shelley’s car but found no incriminating evidence related to John McCabe.

Despite the lack of physical evidence, Walter Shelley became a person of interest. He was brought in for questioning and underwent polygraph tests five times. According to Leone, the tests indicated Shelley was “lying in all vital areas of the questioning.” “If you read the reports,” Leone explained, “now you start seeing Ferreira and Shelley, Shelley and Ferreira.”

Mike Ferreira’s behavior further complicated the investigation. During a joyride with friends, Ferreira unexpectedly claimed to have killed John McCabe. “Yeah you know, I was 16. We were drinking’ jokin you know … ‘Yeah I did it.’ They knew I was jokin,” Ferreira insisted. “I was a joker.” Leone clarified that while police did not find this amusing, Ferreira’s statement could not be substantiated. “Without physical evidence, without a witness statement putting him at the scene … The Ferreira lead kept drying up,” Leone conceded.

The investigation into the murder of John McCabe expanded to include dozens of individuals, from other teenagers and local drug dealers to known pedophiles. For two years, detectives relentlessly pursued every lead. Throughout this period, Bill McCabe dedicated himself to creating a record of his son’s life. “I wasn’t tryin’ to be an author or anything like that. I —I was just lookin’ at ways to hold on to him … keep his memory,” he told “48 Hours.”

Bill McCabe also became a persistent advocate for his son, ensuring the police did not forget John McCabe. “I was always on the phone talking to the police. I’d be up in the middle of the night. She’d be saying, ‘what the hell are you doing up? Get back to bed,'” he recalled. Despite Bill’s unwavering efforts and the police’s initial intensive investigation, no arrests were made in the John McCabe case.

“Shelley and Ferreira went into the service in 1970. So the following year, the two of them left the area,” Leone noted. The McCabe family was left in a state of agonizing uncertainty, without answers, for decades to come.

Decades of Silence and a Cold Case Reopened

As years turned into decades, the John McCabe case grew colder, but Evelyn McCabe’s tormenting questions about her son’s final moments never ceased. “I tried to strangle myself just to visualize what it felt like,” Evelyn confessed, revealing the depth of her anguish. “I wondered … ‘Did he call for me? What kind of a mother was I?’ I wasn’t there for him.”

For a period, Evelyn maintained a place setting for John at their dinner table, a constant, heartbreaking reminder of his absence. John McCabe, remembered as a budding engineer like his father, had a passion for bikes and rebuilding engines.

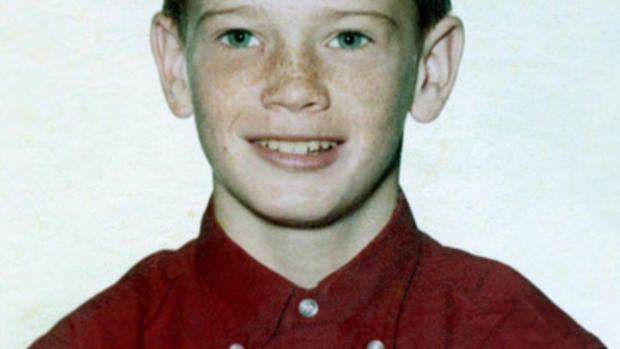

John McCabe on his bicycle

John McCabe on his bicycle

Throughout the years, Bill McCabe continued to meticulously document John’s life story while relentlessly pressing the police for progress in the stalled investigation. “You can’t just do something wrong and not have to pay for it…” he asserted, driven by an unyielding desire for justice for John McCabe.

The case remained stagnant for approximately 30 years until November 2000, when Jack Ward, a childhood friend of John McCabe, honored a long-standing promise to Bill. “He would say, ‘Jackie, have you heard anything about John?'” Ward remembered. “‘You keep your eyes out and let me know.’ And I says, ‘If I ever hear anything, Mr. McCabe, you know, I’m gonna tell you.'”

At a cookout in Tewksbury, Ward encountered Mike Ferreira, a familiar face from their old neighborhood. “We’re all sitting around drinking and that’s when he just blurted out…” Ward recounted. “‘I know who killed John.’ And he said it to me again. … ‘I know who killed John.’ And, you know, finally I said, ‘Who?’ He says, ‘Walter.’ I said, ‘Walter Shelley?’ He says, ‘Yeah.'”

Ward further inquired about Shelley’s motive. “And I said, ‘what would be Walter’s motive to kill John?’ He said, ‘Marla … because of Marla,'” Ward explained. Marla Shiner was Walter Shelley’s girlfriend at the time, and according to Ward, Shelley was intensely jealous, especially because Marla seemed to show interest in John McCabe.

Hesitant and burdened by the gravity of the information, Ward waited before approaching Bill McCabe. “You go knockin’ on somebody’s door and say, ‘Hey — I know who killed your son,’ you better have it right,” he reasoned. Bill McCabe was stunned by Ward’s revelation. “I was shocked when he told me,” said Bill.

“So I scribbled it on a piece of paper and I put it in the Bible … on a page, beginning the book of John so I wouldn’t forget it. … And I immediately called the police,” Bill recounted. Despite Bill’s prompt action, it took three more years and numerous calls from him before police finally visited Ferreira in 2003. By then, Ferreira was working as a forklift operator in Salem, New Hampshire, and Nancy Williams, his friend from 1969, was now his wife.

Nancy Ferreira staunchly defended her husband. “Mike wouldn’t hurt a fly. Never … I know. He wouldn’t,” she insisted. Mike Ferreira offered a different version of the cookout conversation with Jack Ward. “Jackie went and told them I said Walter Shelley killed him. I never said that,” Ferreira claimed. “And at this cookout, you know, I already had a few drinks and he’s runnin’ his mouth, ‘Shelley did it, Shelley did it.’ And this went on all afternoon. …And finally I got sick of hearin’ it. I says, ‘He probably did it.’ Next thing I know, three years, four years later, I got the cops down at my house wantin’ to talk to me about John McCabe.” Ferreira also denied mentioning the jealousy motive to Ward, labeling it “his theory.”

Again, lacking corroborating evidence, the John McCabe case stalled once more. Evelyn McCabe expressed her frustration with the ongoing investigation. “‘It’s going fine.’ It was always going fine,” she said, mimicking the repeated assurances. “And how long did they tell you that?” Schlesinger asked. “And you know what, it was sittin’ on a frickin’ shelf,” Evelyn retorted, highlighting the perceived inaction.

A Breakthrough and Confession in the John McCabe Cold Case

However, the case of John McCabe was not entirely forgotten. In January 2007, Gerry Leone was sworn in as Middlesex County District Attorney. “The Lowell Police Department took it upon themselves to visit me weeks after I’d been elected to say, ‘We’d actually like you to focus on this one and take a hard look at it with us,'” Leone stated.

Reviewing the files, investigators noticed a significant detail in Mike Ferreira’s most recent police interview. While recounting the night of the murder, Ferreira mentioned being with Walter Shelley, but this time, he added another name: Alan Brown. “Edward Alan Brown’s name surfaces as someone who we’re gonna focus on,” Leone explained.

Edward Alan Brown, who was 17 when John McCabe was murdered and lived near the McCabes, had since moved away. When police located him, Brown denied any knowledge of the murder, claiming he had never even heard of it. Leone found this claim suspicious. “So how likely is it that he would never even have heard of the murder of John McCabe in a town the size of Tewksbury,” Schlesinger questioned. “I’d say curious at the time,” Leone replied.

An even more significant development came when police received a call from Brown’s wife. “His wife … told police that she thought he was lying,” Leone revealed. “Carolyn Brown indicates to police that 20 to 25 years earlier her husband had told her about an evening … where he was involved in a young man being killed.”

Yet, the lack of corroborating evidence persisted, hindering progress until 2011 when Detective Linda Coughlin was assigned to the John McCabe case. “You think this case really took off when you met Detective Linda Coughlin,” Schlesinger observed to Evelyn. “Yes, definitely,” she affirmed. Evelyn attributed this to Coughlin’s determined attitude. “Because of her attitude. She … she said, ‘I’m going to get them.’ And she did.”

Detective Coughlin focused her investigation on Edward Alan Brown, who was retired from the Air Force and residing in New Hampshire. During interrogation, Brown initially maintained his innocence but broke down after failing a polygraph test. He confessed to being present when Walter Shelley and Mike Ferreira murdered John McCabe.

Lowell police informed the McCabe family about Brown’s confession and the details of John’s final hours. Roberta McCabe’s immediate question was a heart-wrenching “Why?” The news overwhelmed Bill McCabe, who “started crying, he keeled over on the table…”

On April 15, 2011, nearly 42 years after John McCabe’s body was discovered, Bill McCabe’s relentless pursuit of justice finally yielded results. “Mr. McCabe held our feet to the fire, he never let us forget John McCabe’s murder,” Lowell Police superintendent Ken Lavallee told reporters.

Edward Brown, Mike Ferreira, and Walter Shelley arrested

Edward Brown, Mike Ferreira, and Walter Shelley arrested

The District Attorney’s office announced the indictments of Edward Alan Brown for manslaughter, and Michael Ferreira and Walter Shelley for first-degree murder. These were names known to the police from the beginning, names that had lingered in the shadow of John McCabe’s unsolved murder for decades. Evelyn McCabe revealed the chilling detail, “The murderers came to the wake. And they came to the funeral.”

Trials and Tribulations: Unraveling the Secrets of John McCabe’s Murder

Bringing the accused to trial took almost two years, extending the McCabe family’s agonizing wait. On January 18, 2013, Edward Alan Brown testified against Mike Ferreira, the first defendant to face trial for the murder of John McCabe.

For the first time publicly, Brown detailed the events of the night John McCabe died. He testified that Ferreira and Shelley arrived at his home wanting him to join them.

Edward Alan Brown: They wanted me to go with them to help them.

Prosecutor: Help them do what?

Edward Alan Brown: I didn’t know at the time until I got in the car and we left.

Brown recounted that they were headed towards the Knights of Columbus Hall when he learned their plan: to confront a young man who had been “messing around with Marla” to “teach him a lesson.”

Edward Alan Brown: They said they wanted to go find this kid that had been… uh you know, messing around with Marla to teach him a lesson.

Prosecutor: And how did you know Marla Shiner?

Edward Alan Brown: It was Walter’s girlfriend.

Edward Alan Brown: Michael noticed John McCabe was thumbing. And he said, “There he is.” … And we pulled up next to John, Michael got out and grabbed him and pushed him … in the back seat where I was…

Brown described how Michael Ferreira confronted John McCabe in the backseat of the car as they drove towards a secluded location.

Michael was facing back — at John, tryin’ to — to smack him. And John had his arms up to try to — to stop him from doing that. … We went under the Spaghettiville Bridge …

Brown testified that they drove to a vacant lot, where the situation escalated tragically.

Edward Alan Brown: And we got him outside the car.

Prosecutor: Who pushed John out of the car?

Edward Alan Brown: I did. …I thought they were just gonna slap him around.

Prosecutor: What happened next? Then Michael and Walter wrestled John, tripped him up, and got him on the ground.

Edward Alan Brown testifying at trial

Edward Alan Brown testifying at trial

Brown stated that he and Shelley held John McCabe down while Ferreira tied him up with rope and tape.

Edward Alan Brown: Michael tied his ankles, then went around and tied his — wrists together. Then he took another piece of rope … around his ankles and attached it up to his neck. …they had put tape on his mouth. John’s — squirming, wiggling, trying to get out. … He’s lying on his belly … uh, with his legs up in the air and his — his head turned sideways.

Then they said — that, “This — this’ll teach you to — to mess with Marla anymore.” And we got in the car and left.

After leaving John McCabe, Brown said they drove around, drinking beer. Later, filled with remorse, Brown urged them to return.

Edward Alan Brown: Then — I told ’em we should go back and let him go…

Upon returning to the vacant lot, Brown described Shelley and Ferreira approaching John McCabe.

Edward Alan Brown: Michael and Walter got out of the car and went over to him. They were there for about 30, 45 seconds … and they came quickly back to the car … we started to drive off and one of ’em said that he wasn’t breathing.

John McCabe had died from strangulation. Evelyn McCabe, reflecting on her son’s last moments, expressed her deep sorrow. “I wonder … I wonder what he thought of that night,” she said, her voice heavy with emotion.

Edward Alan Brown: Then they brought me home.

Prosecutor: What did you do?

Edward Alan Brown: I don’t remember. I think I cried.

Brown claimed he kept the murder a secret for 41 years due to fear of Michael Ferreira, stating, “Michael said, ‘If anybody talks to anybody about this, I’ll kill him.'”

Michael Ferreira vehemently denied Brown’s account. “Alan Brown’s a friggin’ liar, and I mean, they know that,” Ferreira asserted. Nancy Ferreira questioned Brown’s credibility, suggesting, “Either he did it with somebody else or by himself, or he is really a messed up human being.”

Eric Wilson, Ferreira’s attorney, argued that police coerced Brown into confessing and offered him a deal to avoid jail time. “My sense of Edward Brown was he was easily led,” Wilson told Schlesinger. “Edward Brown did not walk into Lowell Police Department headquarters and say, ‘Look, I got to get this off my chest.’… After being … interrogated by trained detectives … he was faced with the threat of spending the rest of his life in jail — or he could tell the police what they wanted to hear.” Wilson challenged the jury to consider Brown’s motivations, asking, “The question that I had to answer for the jury is why would he tell them that if he didn’t do it.”

Wilson meticulously cross-examined Brown, highlighting inconsistencies and admissions that the prosecution had provided him with key details about the crime scene.

Eric Wilson: You were fed information it was a dirt lot, right?

Edward Alan Brown: Yes.

Eric Wilson: You were fed information that it was near a railroad tower, right?

Edward Alan Brown: Yes.

Eric Wilson: And you’re being told that Shelley was jealous over Marla Shiner, right?

Edward Alan Brown: Yes.

Leone defended the police procedures, stating, “There are certain pieces of information that an investigator may provide to someone who they’re interviewing to see whether or not they know anything about that, to see whether or not it jogs their memory.” Schlesinger questioned the potential for manipulation, “Well, but — couldn’t that also be a way of telegraphing to the witness what you want him to say?” Leone countered, “Well, in this case that didn’t have to happen, because … Brown was the one who talked about the rope, the tape, the binding of John.”

Wilson argued that Brown’s confession contradicted the original crime scene evidence, pointing out the 1969 police reports which noted “unable to find any evidence of a scuffle.” “There was no suggestion anywhere around John McCabe’s body or the scene that that struggle described by Edward Brown ever took place,” Wilson emphasized. Leone maintained, “Why would Edward Alan Brown lie and implicate himself so directly in what happened unless it was the truth?”

To further undermine the prosecution’s case, Wilson attacked the alleged motive – jealousy over Marla Shiner – by calling her to the witness stand.

Marla Shiner’s Testimony and Lingering Doubts in the John McCabe Case

The prosecution’s case against Michael Ferreira faced significant challenges as their star witness, Edward Alan Brown, faltered under intense cross-examination.

Eric Wilson: Mr. Brown, you’ve lied under oath when you’re scared, right?

Edward Alan Brown: Yes.

Eric Wilson: You’ve lied under oath when you’re nervous, right?

Edward Alan Brown: Yes.

Eric Wilson: You’ve lied under oath when you’re frightened, right?

Edward Alan Brown: Correct.

Eric Wilson: You still can’t get your facts straight, can you?

Edward Alan Brown: No.

In response, prosecutor Tom O’Reilly called Detective Linda Coughlin to refute claims that she had coerced Brown’s confession.

Tom O’Reilly: At any point did you feed him information as to the investigation?

Det. Coughlin: Never.

However, Wilson argued that Detective Coughlin exhibited tunnel vision, overlooking other potential suspects in the John McCabe murder.

Eric Wilson: There were a number of investigative reports and material that you either overlooked or didn’t even know about, true?

Det. Coughlin: I don’t know what you’re referring to.

Eric Wilson: How about Richard Santos?

Richard Santos, identified in a 1974 Tewksbury police report as a suspect, had committed a crime strikingly similar to the murder of John McCabe – abducting, binding, and gagging a young woman. “This young woman was abducted on Route 38,” Wilson detailed. “Her feet were bound, her hands were tied behind her back, her mouth was duct taped, and her eyes were taped shut.”

Leone acknowledged Santos as a suspicious figure. “All of the facts that surround Santos as a possible subject lead you to be suspicious,” he stated. “But there was never anything tying him to motive, opportunity, means.” Despite the lack of direct evidence linking Santos to John McCabe, the judge allowed the jury to consider him and another suspect, Robert Morley.

Robert Morley, a 25-year-old local man known to Ferreira and Shelley and suffering from mental illness, was also considered a potential suspect.

Eric Wilson: He was labeled … long before you were assigned this case, as a strong suspect, right?

Det. Coughlin: There is a report that uses the word for him, “strong suspect”. In the very same report, mentions Mr. Ferreira as a prime suspect.

Morley’s own brothers had informed police of their suspicions shortly after John McCabe’s murder. “Morley’s own brothers went in and said that they thought he might’ve been involved in it,” Schlesinger noted to Leone. “Yeah … they thought he might have,” he confirmed. Leone downplayed the significance of this, stating, “I think what happens in matters like this is people will say, ‘Sure, you should take a look at X or Y because they have a profile of somebody who would do something like this and they were around the area at the time.’ But then you have to look at the evidence and see whether or not the evidence leads you to believe that they had anything to do with it,”

Eric Wilson: Did the brothers have any specific evidence that you’re aware of?

Det. Coughlin: They did not.

Wilson revealed that Morley fled to Florida the day after police questioned him and later committed suicide. “He split to Florida the day after he was questioned by police,” Wilson explained. “Mr. Morley — years later … committed suicide.”

Eric Wilson: you learned of his death, suicide right? He jumped off a bridge, right?

Det. Coughlin: His brother says he fell off a bridge.

The defense then called Marla Shiner to challenge the prosecution’s motive of jealousy.

John McCabe on his bicycle

John McCabe on his bicycle

Shiner testified that John McCabe never flirted with her and directly contradicted Brown’s testimony that she was Walter Shelley’s girlfriend in September 1969 and that Shelley was jealous of John McCabe.

Defense: Did you ever go to a dance with John McCabe?

Marla Shiner: Never.

Defense: Was it ever conveyed to you that he had any type of romantic interest in you in August or September of 1969?

Marla Shiner: None.

Bill McCabe acknowledged the potential for misinterpretation, regardless of Shiner’s actual feelings. “She could have been — just stopped and said hello to John, and Shelley could have walked by and seen it … and he’s gonna explode,” he speculated.

Shiner then delivered a further blow to the prosecution’s timeline.

Prosecutor: September 26th, 1969 were you dating Walter Shelley?

Marla Shiner: No … I was not dating Walter – when John McCabe died.

Prosecutor: When did you start dating him then?

Marla Shiner: I believe it was after that death.

Prosecution: How old were you?

Marla Shiner: 13.

Prosecution: You were 13 in September of 1969.

Marla Shiner: Oh I don’t know I can’t do the math right here.

Police records, however, indicated Shiner had previously stated she was dating Shelley at the time of John McCabe’s murder and had begun seeing him at age 12.

Prosecutor: You didn’t tell the police that you were dating Walter Shelley in 1969 when John McCabe was killed?

Marla Shiner: I — no — I don’t believe I did tell them that.

Roberta McCabe questioned Shiner’s truthfulness, “Why lie about dating someone, unless it was because of her that John was murdered,” she suggested. Shiner declined an interview with “48 Hours.” She eventually married Walter Shelley, but the marriage was short-lived, and she described him as “very violent.” When asked if Walter Shelley was a jealous man, Shiner responded, “Absolutely.”

Edward Alan Brown testifying at trial

Edward Alan Brown testifying at trial

After a hard-fought trial, the jury deliberated for just five hours before reaching a verdict in the case of Michael Ferreira: not guilty of the murder of John McCabe.

A Father’s Heartbreak and a Second Trial for Justice in the John McCabe Case

“I told Michael that we had to hope for the best but be prepared for the worst. And — he was ready for that,” said Wilson, reflecting on the tense anticipation before the verdict. For the McCabe family, the verdict represented the culmination of over four decades of relentless waiting and struggle.

“What did you think the verdict was gonna be?” Schlesinger asked Evelyn McCabe. “Guilty. My God, he was guilty. If for no other reason, he was there,” she responded, expressing her profound disbelief and disappointment. Bill McCabe echoed her sentiment, “It’s hard to understand how the jury could, you know, anticipate otherwise.”

Too ill and emotionally strained to be in court, Bill McCabe waited anxiously in another room as Evelyn and their daughters endured the devastating verdict. Not guilty. The courtroom was stunned, including Michael Ferreira himself.

“When the verdict came in, when you heard that — that Ferreira had been acquitted -” Schlesinger asked Evelyn. “I had to go tell my husband that,” she replied. “Were you afraid to tell him?” “Yes,” Evelyn confessed. “I was afraid he was gonna die.”

Tragically, Evelyn’s fears were realized. Just four days after the verdict, Bill McCabe’s heart failed, and he passed away, seemingly succumbing to the crushing weight of the outcome. “What do you think killed your husband?” Schlesinger asked Evelyn. “Stress. The stress of the trial,” she answered, her voice filled with sorrow.

As Evelyn McCabe laid her husband to rest beside their son, John McCabe, the District Attorney’s office faced a critical decision: whether to proceed with the trial of Walter Shelley.

Justice, Finally, for John McCabe: A Guilty Verdict After 44 Years

“I still don’t believe Bill is gone. I can still hear him snore in the night. And then I feel the bed. He’s not there,” Evelyn McCabe grieved, her voice filled with the fresh pain of loss. Despite her heartbreak, she was resolute in honoring her husband’s dying wish. “He laid in the hospital bed, and I said, ‘I’ll pick up and take over for you,'” Evelyn recounted, determined to see justice served for John McCabe.

Roberta McCabe shared her father’s unwavering desire, “And my father just kept prayin’ and sayin’ to me, ‘Before I die, we have to find out who did this.'”

Even some jurors in the Ferreira trial wrestled with the outcome. Juror Michael Duquette admitted, “It was very difficult” to acquit Ferreira. Duquette explained the jury’s skepticism towards Edward Alan Brown’s testimony. “No. …They just felt that he was not telling the truth,” he stated. “They felt that he had been fed information. And that didn’t make a ton of sense to me. Maybe he wasn’t the best witness. But I just can’t see somebody saying, ‘I did it,’ when they didn’t do it.” Duquette revealed that he and some jurors believed Ferreira was guilty of manslaughter but were constrained by the available charges. “Manslaughter. And it wasn’t an option,” he said.

Despite the setback of Ferreira’s acquittal, prosecutors decided to proceed with the trial of Walter Shelley. “The acquittal in the Ferreira case didn’t do anything to lessen our belief that we had the right people who were responsible for killing John McCabe,” Gerry Leone affirmed.

On September 3, 2013, seven months after Ferreira’s acquittal, Walter Shelley stood trial. Shelley, who was 17 at the time of John McCabe’s murder, was now 61 and had lived quietly in Tewksbury, near the McCabe family, for years. Facing a first-degree murder charge, Shelley potentially faced life in prison.

The prosecution presented essentially the same case as in Ferreira’s trial, relying on the same witnesses: Marla Shiner, Detective Linda Coughlin, and Edward Alan Brown.

“Was it any easier to sit through the second trial?” Schlesinger asked Roberta McCabe. “No, I wanna say it was harder,” she replied. “Dad wasn’t there for backup.” This time, Brown appeared more composed and confident, renewing the McCabe family’s hope. “I can keep my fingers, my toes, everything crossed,” Roberta expressed.

During closing arguments, the defense attorney labeled Brown a liar, while the prosecution emphasized the unlikelihood of Brown falsely confessing to such a serious crime. After a week-long trial, the case went to the jury. This was the McCabe family’s final chance to see someone held accountable for John McCabe’s murder.

“We had faith that the jury was gonna come with the right answer this time,” Debbie McCabe said. Two days later, a verdict was reached. Walter Shelley’s family waited anxiously, while Evelyn McCabe remained outside the courtroom, unable to bear another potential “not guilty” verdict.

Edward Alan Brown testifying at trial

Edward Alan Brown testifying at trial

Guilty. Walter Shelley was found guilty of murder and sentenced to life in prison. His knees buckled as the verdict was read. This jury believed Edward Alan Brown.

“So when you heard ‘guilty,’ do you remember the first thing you thought?” Schlesinger asked Roberta McCabe. “I thought my father would be proud,” she said. “We got one of them.”

In a case marked by twists and turns, justice was finally served for John McCabe, albeit with a stark contrast: one defendant acquitted, the other convicted, based on largely the same evidence.

Edward Alan Brown testifying at trial

Edward Alan Brown testifying at trial

Evelyn McCabe visited the graves of John and Bill McCabe. “John, guess what? We got him. … Billy, it turned out beautifully,” she whispered. “Please John, please take great care of him till I get there, please? And then I will.”

Bill McCabe did not live to witness the final chapter, but his unwavering dedication ensured the story of John McCabe’s life and death, a story four decades in the making, finally reached a form of closure. John McCabe remains forever 15 years, six months, and two weeks old in memory, but no longer without justice.

Michael Ferreira later pleaded guilty to perjury and received probation. Walter Shelley’s conviction was downgraded to second-degree murder due to his juvenile status at the time of the crime, making him eligible for parole after 15 years. Evelyn McCabe passed away in August 2016, but her daughters continue to pursue a wrongful death suit against Ferreira, Shelley, and Brown.