John MacColl

John MacColl

John Maccoll (1860-1943) stands as a towering figure in the history of Scottish bagpiping, an era often lovingly referred to as its “Golden Age.” His name is synonymous with exceptional talent, not only as a piper but also as a prolific composer whose works continue to resonate in the piping world today. MacColl’s legacy extends beyond mere performance; he embodied the spirit of dedication and versatility, excelling in various Highland arts and leaving an indelible mark on competitive piping and music composition.

Born the fourth son of Dugald MacColl, a tailor and respected piper from Kentallen, John MacColl was destined for a life intertwined with music. While his brothers also pursued piping, John distinguished himself early on with an unwavering ambition to not just participate, but to dominate. His initial instruction came from his father, laying a solid foundation before he sought guidance from renowned figures like Donald MacPhee (a celebrated pipe music editor and player) and Pipe-Major Ronald MacKenzie of the Black Watch, a distinguished piper himself. MacKenzie’s mentorship, following MacPhee’s passing, proved invaluable, shaping MacColl’s technique and musical understanding.

MacColl’s entry into competitive piping at 17 in 1877 was met with the formidable presence of piping giants such as Robert Meldrum and John MacDougall Gillies. Early victories were elusive, yet his determination remained unyielding. A turning point arrived in 1880 when he became the piper to MacDonald of Dunach. This appointment allowed him to dedicate himself fully to his passion. The subsequent years witnessed MacColl’s ascent to the pinnacle of competitive piping. He clinched the prestigious Gold Medal at Oban in 1881, followed by the Prize Pipe at Inverness in 1883, and the Former Winners’ Gold Medal at Inverness in 1884. His triumphs continued into the new century, securing the Clasp at Inverness in 1900 and first prize at the Paris Exhibition in 1902, solidifying his international reputation.

Beyond piping, John MacColl was a true Highland games athlete. His son John recounted stories of his father seamlessly transitioning between disciplines: completing a Highland dance, shedding his kilt to reveal running shorts underneath, competing in foot races, and then redressing for the next dance event. This versatility was not merely for show; it was a professional approach to maximize earnings on the games circuit, supplementing his income from piping, dancing, and teaching. In an era where prize money was significant, MacColl’s diverse skills allowed him to thrive, reportedly earning £40 in an afternoon in the late 1800s. This financial success afforded him the leisure to explore other passions, including yachting, golf, shinty, fiddling, Gaelic singing, and further honing his compositional talents.

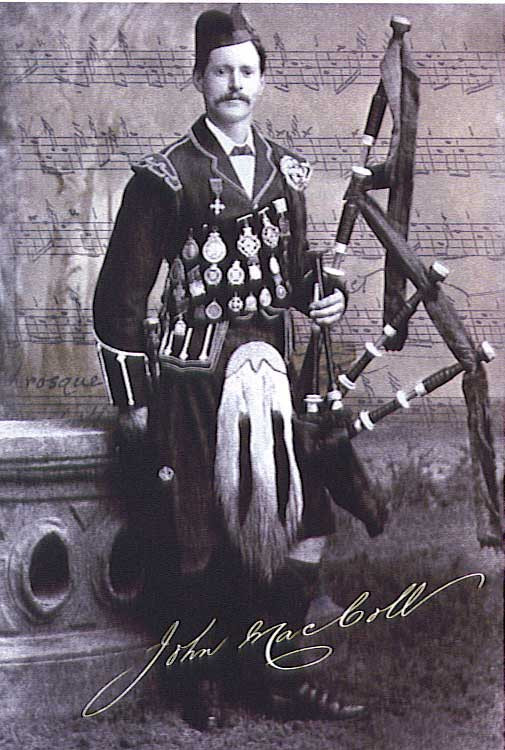

This previously unpublished photo of John MacColl competing, likely in the 1890s, was taken from a Magic Lantern image discovered by Andreas Hartmann-Virnich in 2012.

This previously unpublished photo of John MacColl competing, likely in the 1890s, was taken from a Magic Lantern image discovered by Andreas Hartmann-Virnich in 2012.

His contributions extended to military piping as well, serving as pipe-major for the 3rd Battalion of the Black Watch and later with the Scottish Horse. He also played a crucial role in education, training pipers and teaching piobaireachd for the Piobaireachd Society, ensuring the preservation and progression of traditional piping forms.

John MacColl, alongside contemporaries like Willie Lawrie and G. S. McLennan, revolutionized light music composition, particularly the competition march. They elevated the march form to unprecedented heights, creating pieces of enduring musicality and technical brilliance that remain benchmarks today. Marches like Mrs. John MacColl, Jeannie Carruthers, and The Argyllshire Gathering are testaments to his compositional genius and are staples in piping repertoire. His body of work includes seven of the most celebrated 2/4 competition marches, a remarkable achievement.

While renowned for his light music prowess, MacColl’s piobaireachd performances garnered varied opinions. Despite winning major prizes in piobaireachd, he didn’t achieve the same level of dominance as in marches. Some critics felt his piobaireachd lacked the emotional depth evident in his light music. However, respected judges like John MacDonald of Inverness praised his performances, citing one rendition of “I Got a Kiss of the King’s Hand” as exceptionally harmonious. MacColl’s compositional output also included piobaireachd, with two of his three known pieces, Lament for Donald MacPhee and N.M. MacDonald’s Lament, winning composition contests. Sadly, his third piobaireachd is now lost to time.

In 1908, John MacColl transitioned from the Highland games circuit to a new chapter, joining the Glasgow firm of R. G. Lawrie as manager of their newly established bagpipe making branch. This move coincided with John MacDougall Gillies taking a similar position at Henderson’s pipemaking shop. This era saw these two giants of piping at the helm of renowned instrument makers, contributing to a golden age of bagpipe craftsmanship. The instruments produced by Lawrie’s and Henderson’s during this period are considered among the finest ever made. MacColl retired from Lawrie’s in 1936. Throughout the early decades of the 20th century, he and MacDougall Gillies fostered a thriving piping community in Glasgow, transforming it into a global center of piping excellence that persists to this day.

John MacColl passed away on June 8, 1943, leaving behind a rich musical heritage. As a final tribute, John MacDonald of the Glasgow Police played Lament for the Children at his funeral, a poignant musical farewell to a true master of the pipes. His compositions and his influence continue to inspire and shape the world of bagpiping.

Based on notes from Piping Times, (February 1998, May 1970), ‘A History of Piping’ (Captain John A. MacLellan teaching handout, Army School of Piping) and ‘Pipers’, by Dr. William Donaldson, Birlinn Ltd., 2005.