John Minchin Lloyd, a name forever entwined with the grim narrative of the Lincoln assassination, often exists in historical accounts as a shadowy figure, defined solely by his pivotal testimony against Mary Surratt. While his words undeniably contributed to her conviction and execution, the life of John Lloyd extends far beyond the confines of that infamous trial. Venturing beyond the well-trodden paths of assassination conspiracy, a deeper exploration reveals a man of varied experiences, whose story, though punctuated by tragedy and misidentification, offers a richer understanding of a witness in a pivotal moment of American history. This article delves into the life of John M. Lloyd, clarifying misconceptions and illuminating the narrative beyond his connection to Mary Surratt, exploring his life as a bricklayer, a family man, and an individual caught in the crosscurrents of history.

Advertisement that mistakenly identified John M. Lloyd as a fertilizer agent, highlighting the confusion with his cousin.

Advertisement that mistakenly identified John M. Lloyd as a fertilizer agent, highlighting the confusion with his cousin.

The Case of Two John Lloyds: Untangling a Historical Mix-Up

Initial research into John M. Lloyd’s life outside the assassination narrative led down an unexpected path, highlighting a common pitfall in historical investigation: mistaken identity. A seemingly promising discovery emerged in the form of newspaper advertisements for fertilizer, bearing the name “John M. Lloyd.” For anyone familiar with the Lincoln assassination, this name immediately triggers recognition – John Minchin Lloyd, the tenant of Mary Surratt’s tavern and a crucial witness in the conspirators’ trial.

Lloyd’s testimony at the trial painted a damning picture of Mary Surratt. He recounted how, on the very day President Lincoln was assassinated, Surratt visited her tavern and instructed him to have “shooting irons ready” and to expect a party to collect them that night. This testimony was instrumental in securing Surratt’s conviction and subsequent execution.

Given this background, the fertilizer advertisements seemed intriguing. Could this be another facet of John M. Lloyd’s life? Perhaps a post-Civil War entrepreneurial venture to supplement his income as a bricklayer, his profession listed in census records and city directories of Washington D.C.? The advertisements themselves provided clues, mentioning Lloyd’s Southern Maryland roots and his regular visits to Charles and St. Mary’s counties to meet clients and discuss their agricultural needs. The advertisements ceased around 1890, aligning neatly with the death of “our” John M. Lloyd in 1892. One advertisement even explicitly stated the name “John Minchin Lloyd,” seemingly confirming the connection.

The tantalizing prospect of uncovering a hidden career as a guano supplier for Southern Maryland emerged. For those who believe Lloyd fabricated his testimony against Mary Surratt, this discovery could be twisted into a cynical narrative about Lloyd being adept at selling “crap” in more ways than one. A blog post was practically writing itself, ready to unveil this “new” dimension of John M. Lloyd’s life.

However, a crucial piece of genealogical research, The Lloyds of Southern Maryland, served as a necessary corrective. This meticulously researched family history, readily available online, dedicates several pages to John M. Lloyd and had previously been consulted for details of his early life. Revisiting this source revealed a critical distinction: there were two John M. Lloyds – cousins with the same name, living in the same region.

The genealogical record clearly distinguishes between John M.¹, “our” John M. Lloyd of Lincoln assassination fame, and John M.², his cousin, a successful businessman specializing in fertilizer. The advertisements, the Southern Maryland connection, the timeline – all belonged to the other John Minchin Lloyd, ten years younger than the tavern keeper. The fertilizer king was not the same man who testified against Mary Surratt.

This humbling realization underscores the importance of thorough research and the potential for historical misidentification, even for the author of the Lloyd genealogy who momentarily confused the two cousins’ endeavors.

John M. Lloyd: Life After Surratt and Beyond the Tavern

Following the tumultuous events of Lincoln’s assassination and the conspirators’ trial, John M. Lloyd sought to rebuild his life away from the Surrattsville tavern, returning to Washington D.C. and his original trade. While he had been a founding member of the Metropolitan Police Force before the Civil War, he did not rejoin the force. Instead, from October 1865 onwards, John M. Lloyd resumed his career as a bricklayer and contractor. This was his primary occupation, dispelling the fertilizer agent misconception and any notions of him being a produce agent or “Southern Maryland bat poop king.” He was, at his core, a bricklayer.

Yet, Lloyd’s connection to the Lincoln assassination wasn’t entirely severed. When John Surratt Jr., Mary’s son, was apprehended and brought back to the United States for trial, John M. Lloyd was once again called to testify. After this second trial, Lloyd largely receded from the public eye, living a seemingly quieter life in Washington D.C. with his wife.

However, life occasionally intruded upon his relative anonymity. In 1883, an incident brought John M. Lloyd back into the news, showcasing a glimpse of his past as a police officer and a man not to be trifled with.

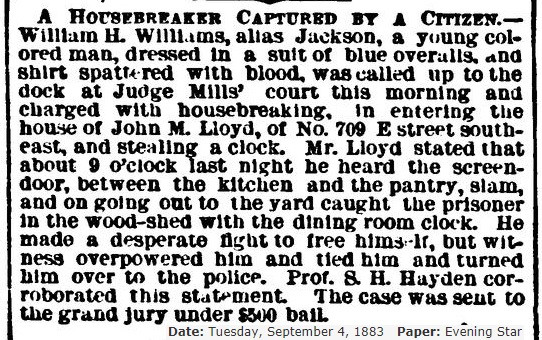

Newspaper clipping about John M. Lloyd apprehending a burglar in his home in 1883.

Newspaper clipping about John M. Lloyd apprehending a burglar in his home in 1883.

One night, Lloyd discovered a burglar in his house. The ensuing confrontation, though not detailed in the newspaper report, clearly favored the former policeman. The article mentions the thief appearing before a judge “spattered with blood,” suggesting Lloyd delivered a decisive beating to the intruder. The severity of the sentence – three years in prison for stealing a clock – further hints at the forceful nature of the capture. This episode reveals that the spirit of the lawman still resided within John M. Lloyd, even years after leaving the police force.

Years later, in 1892, another newspaper snippet offered a lighter glimpse into Lloyd’s life, portraying him as a social man who enjoyed the company of friends and family.

Newspaper item about a leap year party hosted by John M. Lloyd in 1892.

Newspaper item about a leap year party hosted by John M. Lloyd in 1892.

The article mentions a leap year party hosted by Lloyd for his friends and relatives, painting a picture of a man who, despite the shadow of his past, engaged in social life and maintained connections with his community. This dance, however, proved to be one of John M. Lloyd’s last.

Tragedy struck later in 1892. While working on a construction site, a fatal accident cut short John M. Lloyd’s life. A lifelong bricklayer, his death ironically came at the hands of the very material he worked with.

His great-niece, Beatrice Petty, provided a poignant recollection of her “Uncle Lloyd,” describing him as a “kindly man” and a “Santa Claus” figure to the family. She recounted the details of his accident: inspecting construction work, he stepped onto a scaffold that gave way under his weight and a load of bricks, crushing him. He succumbed to his injuries on December 18, 1892, his 68th birthday. His death certificate attributed the cause to “cerebro-spinal concussion.”

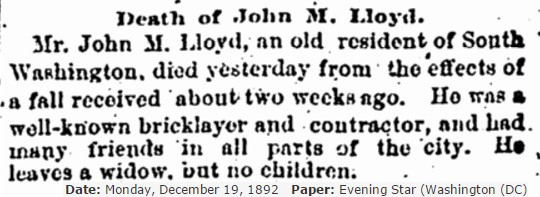

Washington D.C. newspapers carried brief obituaries, notably omitting any mention of his connection to the Lincoln assassination.

Obituary for John M. Lloyd in a Washington D.C. newspaper, focusing on his profession and accident.

Obituary for John M. Lloyd in a Washington D.C. newspaper, focusing on his profession and accident.

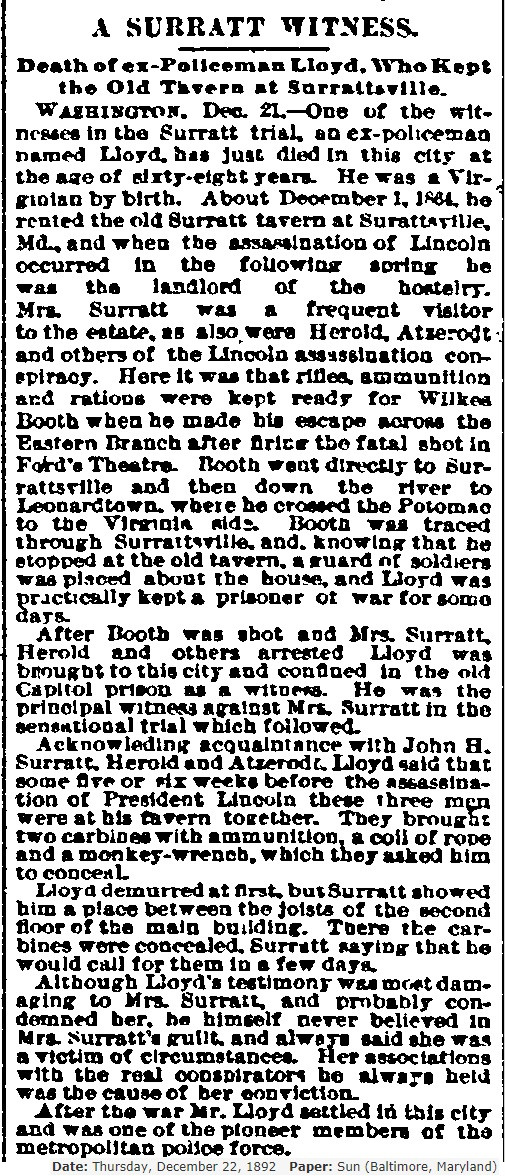

However, newspapers elsewhere resurrected his association with Mary Surratt in their obituaries, highlighting the event that had indelibly marked his place in history.

Obituary for John M. Lloyd that emphasizes his role in the Mary Surratt trial.

Obituary for John M. Lloyd that emphasizes his role in the Mary Surratt trial.

Resting in the Shadow of History

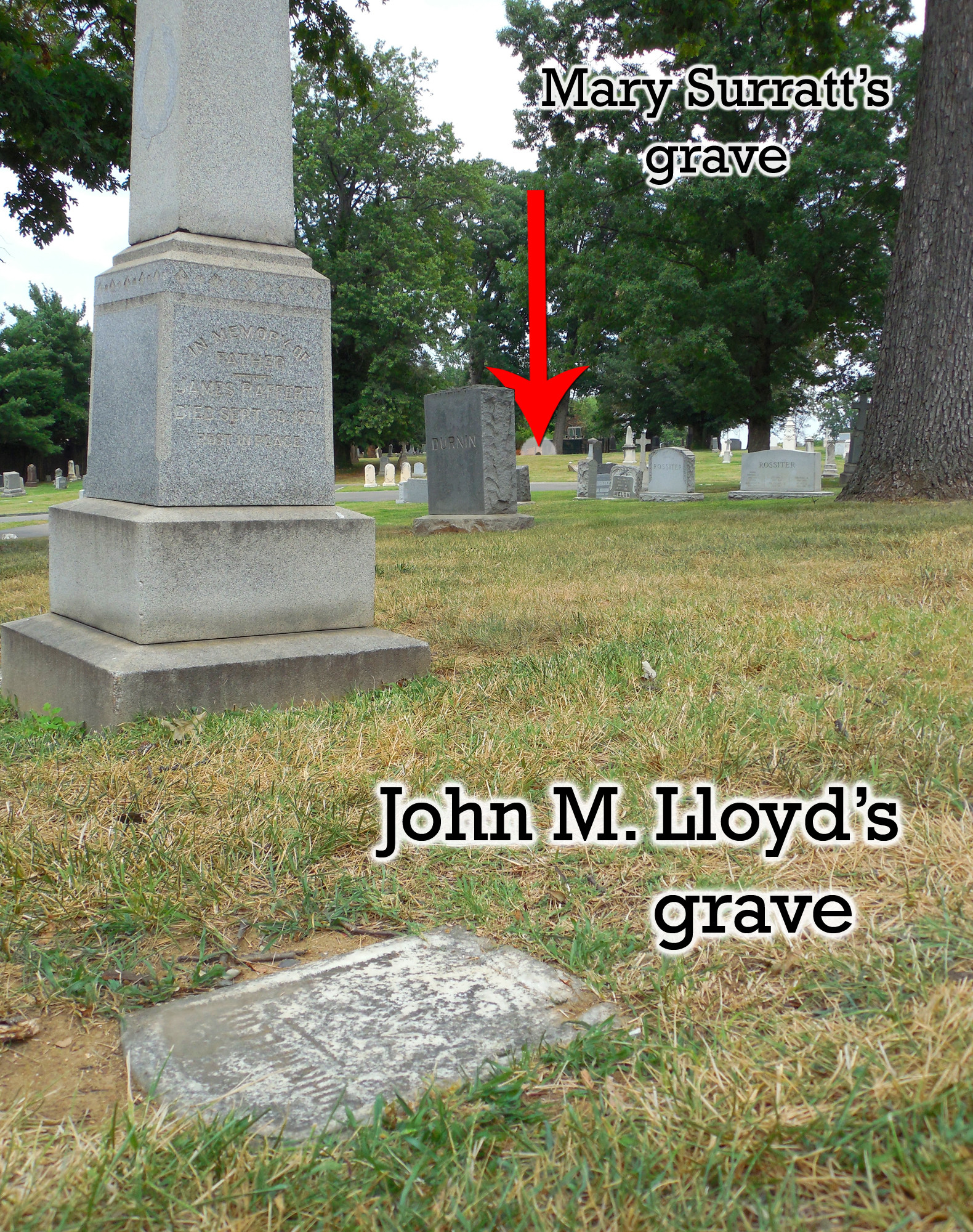

John M. Lloyd was laid to rest in Mount Olivet Cemetery, a Catholic cemetery in Washington D.C. where he had owned a plot since 1865. His grave was marked with a simple marble stone inscribed with only “John M. Lloyd.” Over time, the gravestone fell and became buried until assassination researcher Richard Smyth rediscovered it.

John M. Lloyd's simple gravestone in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

John M. Lloyd's simple gravestone in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Mount Olivet Cemetery holds the remains of several individuals connected to the Lincoln assassination, including Thomas Harbin, Detective James McDevitt, Honora Fitzpatrick, and Father Jacob Walter. Most notably, Mary Surratt is also buried there, her grave similarly marked with a modest stone bearing only her name.

Mary Surratt's grave in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

Mary Surratt's grave in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

In a final, perhaps unintended irony, John M. Lloyd, the bricklayer who never sold fertilizer, now rests in Mount Olivet, approximately 100 yards from Mary Surratt, the woman whose fate was so heavily influenced by his testimony. Their proximity in death serves as a silent testament to the enduring and complex entanglement of their lives within the Lincoln assassination narrative.

A view showing the relative proximity of John M. Lloyd and Mary Surratt's graves in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

A view showing the relative proximity of John M. Lloyd and Mary Surratt's graves in Mount Olivet Cemetery.

References:

Lloyds of Southern Maryland by Daniel B. Lloyd. https://archive.org/details/lloydsofsouthern00lloy

Newspaper clippings from GenealogyBank.com