John Lee Hancock stands as a fascinating figure in Hollywood, a filmmaker who defies easy categorization. He seamlessly transitions between writing and directing, often helming projects penned by others while also bringing his own scripts to life. This versatility, coupled with a reluctance to dissect his creative choices, makes him an intriguing subject for any film enthusiast. A conversation with Hancock reveals a deep passion for storytelling, driven by the story itself rather than a predetermined artistic agenda.

Hancock’s career trajectory took off when Clint Eastwood recognized the power of his script for A Perfect World (1993). This overlooked gem, which tells the poignant tale of an escaped convict and a young hostage forging an unexpected bond, is a must-watch for any cinephile. Eastwood’s faith in Hancock continued with Midnight in the Garden of Good and Evil (1997), which Hancock penned. By 2002, Hancock stepped into the director’s chair with The Rookie, showcasing his ability to direct narratives not of his own creation. Since then, he has navigated a diverse path, alternating between directing his original scripts and interpreting the visions of other writers. His directorial credits include the sports drama The Blind Side (2009), the crime thriller The Little Things (2021), and the Stephen King adaptation Mr. Harrigan’s Phone (2022). He has also delved into significant chapters of 20th-century American history with films like Saving Mr. Banks (2013), The Founder (2016), and The Highwaymen (2019). While Hancock may not explicitly draw connections between these diverse projects, a closer look reveals a filmmaker deeply engaged with American narratives and character-driven stories.

For aspiring screenwriters and filmmakers, John Lee Hancock’s journey offers valuable lessons. His approach to craft, his project selection process, and his experience revisiting and directing The Little Things decades after writing it provide a rich case study. While Hancock may resist over-analyzing his creative motivations, his work prompts us to consider our own artistic processes. Is it essential for artists to dissect their every decision? Should every creative choice be readily explainable? These are compelling questions to ponder when examining Hancock’s filmography.

Share

COLE HADDON: Let’s begin with a lighter question that might reveal deeper insights. What cinematic comfort food do you find yourself returning to? Are there films you watch repeatedly when you need a creative boost?

JOHN LEE HANCOCK: I’m not sure I would categorize the films I revisit as “comfort food,” but they undoubtedly scratch a creative itch and inspire me to strive for improvement as both a writer and a director.

CH: Could you give us some examples?

JLH: The Conversation is a masterclass in subtlety and precision. The entire film hinges on the nuanced inflection of a single two-letter word, “us.” The line “He’d kill us if he had the chance” can be interpreted in two drastically different ways depending on where the emphasis lies. Is the speaker afraid for their own life, or are they preemptively justifying a violent act? It’s brilliant. The Verdict is another film I consider near-perfect. Each viewing reveals new layers and details. And really, anything by Sidney Lumet. Lonely Are the Brave, directed by David Miller and written by Dalton Trumbo, is a lesser-known gem. Kirk Douglas himself considered it his favorite film. I’m drawn to its theme of an individual “born a hundred years too late.”

Depending on the project I’m working on, I often turn to films within that genre for inspiration. Recently, while working on a spy-related project, I reread The Spy Who Came in from the Cold and rewatched the film adaptation. Both are exceptional.

CH: I revisited The Conversation last year and The Verdict this year, and I wholeheartedly agree with your assessments. It’s been two decades since I last saw Lonely Are the Brave, so I’ll definitely add that to my watchlist. Speaking of spy narratives, if you haven’t seen the British series “A Spy Amongst Friends” yet, I highly recommend it.

So, you find inspiration in films, and I assume television and perhaps other art forms, as you work. Can you describe your script-breaking process? While each project is unique, have you identified any consistent approaches over the years?

JLH: Hmmm, breaking a script. Each story originates from a different place, so the approach is always evolving.

CH: What about adaptations specifically?

JLH: When adapting a book, I typically read it two or three times initially. Then, I do a detailed page-by-page read, highlighting and making notes on essential elements that must be included in the script. Adapting a book largely involves deciding which sixty percent of the source material to omit from the film. After this initial process, I start to create a loose outline to establish the structure and build from there.

“Doing an adaptation is largely about deciding which sixty percent of the book to leave out of the movie.”

JLH (cont’d): For original ideas, I jot down numerous loose notes and try to devise a structural framework fairly quickly to determine if it has the potential for a feature film. Once I have an outline and a strong grasp of the story’s thematic core, I begin what Scott Frank calls a “vomit draft.” For me, this signifies unfettered writing, almost always resulting in overwriting, to truly discover the heart of the characters and the plot. I don’t focus excessively on page count at this stage but pay attention to the overall shape of the script. Then, the process becomes one of rewriting and refining until I believe I’ve exhausted every avenue to make it work. From a subject matter perspective, as I mentioned, I immerse myself in films and music that align with the thematic mood of the project, essentially seeking inspiration wherever I can find it at that moment. Each writing experience is subtly different.

CH: Every. Time. I think many aspiring screenwriters underestimate the fluidity of screenwriting and the diversity of approaches within the craft.

Let’s rewind a bit to 1986. You are four years out of Baylor Law School and on the cusp of making a significant life change, leaving your burgeoning legal career to pursue filmmaking. How long had this transition been brewing, and how much did it frighten you – and your family – at the time?

JLH: I had been writing short stories, plays, and my first screenplay while practicing law. There came a point in my legal career where I needed to commit to the firm – with partnership on the horizon – or take a leap and try to earn a living doing what I would, and did, do for free. My parents, both public school teachers who financed my law school education, were incredibly supportive. I believe they felt I should pursue my passion and that if it didn’t materialize within a couple of years, I could always return to Houston and resume practicing law. I’m sure they had their private reservations, but they kept them to themselves.

John Lee Hancock and Billy Bob Thornton on the set of *The Alamo*. Source: WB

John Lee Hancock and Billy Bob Thornton on the set of *The Alamo*. Source: WB

CH: Having watched nearly every film you’ve been credited on, it’s impossible not to notice the recurring Texas setting. Our upbringing often defines us, and many artists, at least, spend their careers circling back to their origins. Tell me how Texas feels when you think about it. I mean that literally – how does it manifest in your heart, your mind, your soul?

JLH: I believe that if you are born in Texas, it occupies a permanent place within you, regardless of where life takes you. The ingrained notion that Texas was once an independent nation is instilled from a young age, almost to the point where it feels like your passport should be issued by the Republic of Texas.

I have vivid sensory memories of Texas: the distinct feel of the heat, the scent of humidity on a summer night, and the diverse horizons that unfold as you travel across the state. These elements feel intrinsically familiar, almost like characters in any story I write set in Texas. I can’t help but hear the nuances of the language – the West Texas drawl, the clipped East Texas accent, and everything in between. These linguistic melodies permeate stories, as if demanding that any tale you consider must be set in Texas. In a way, the state exerts an unfair advantage over you in this regard.

“I have instant recall of how the heat feels different there, how the humidity on a hot summer night smells, and the various horizons you take in when you travel within the state.”

CH: It sounds like a far more organic and cost-effective way to inspire films about Texas than production subsidies.

JLH: I had the pleasure of working on films in Texas from around 1992 to 2004, and it was a fantastic period. I wish production incentives comparable to Georgia or Louisiana were available, because Texas offers such diverse locations for filming. We considered shooting The Blind Side in Texas, but we realized a $4 million saving by filming in Atlanta. On a lower-budget film, that’s a significant amount.

CH: I wasn’t aware that Texas’s production incentives were that weak. So, Texas imprinted itself on your identity, perhaps even shaped it. Whatever the case, it’s an indelible part of you. I’m curious, did your upbringing and the way you were taught to see the world – perhaps your approach to conflict or deception – influence your adjustment to Hollywood? Did it hinder you, or perhaps become a surprising strength in such a unique industry culture?

JLH: That’s an insightful question. I believe being raised to always be punctual has been immensely helpful in Hollywood, where chronic lateness seems to be the norm. I also try to rely on “common sense” when facing challenges. I think the fact that I practiced law is often perceived as more intriguing than my Texas origins, to be honest.

Share

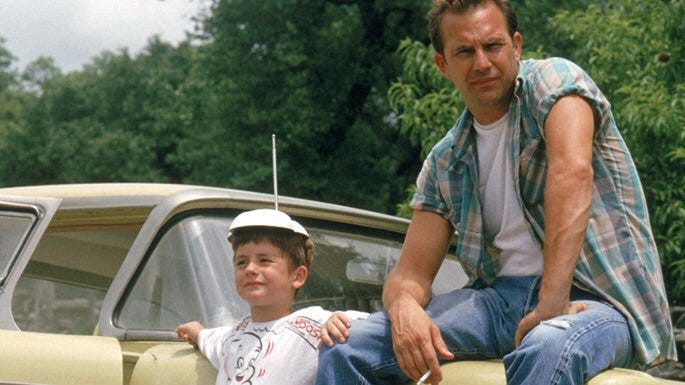

T.J. Lowther and Kevin Costner in *A Perfect World*. Source: WB

T.J. Lowther and Kevin Costner in *A Perfect World*. Source: WB

CH: One of your early produced screenplays is also one of my favorite American films of the 1990s: A Perfect World. Set in Texas in the early 1960s, it tells the story of an escaped convict who takes a young boy hostage. Clint Eastwood directed and co-starred alongside Kevin Costner as the convict. There are certainly worse ways to break into Hollywood, right? Given the impact A Perfect World had on your career – and because of my personal appreciation for it – could you share the origin of the idea?

JLH: A Perfect World emerged from a fusion of three different story ideas I was developing. I always kept a collection of potential ideas that I would revisit and add notes to, hoping that eventually, enough elements would coalesce into a complete screenplay.

The first idea revolved around a Texas Ranger in the twilight of his career, tasked with assisting in the coordination and grappling with the aftermath of President Kennedy’s fateful visit to Dallas.

The second story was loosely inspired by an incident where a boy I knew was kidnapped by escaped inmates and spent a few days with them before they were apprehended without incident, and the boy was safely returned home. I was struck by the apparent normalcy of his time with and reactions to the inmates. If I recall correctly, they spent a lot of time watching television in a farmhouse.

The third element was more of a visual image. Growing up in Longview, we didn’t have much money, so I vividly remember the first time we could afford store-bought Halloween costumes. My brother Joe, maybe four years old at the time, was Casper the Friendly Ghost and wore that costume practically until the following spring. I would often see him playing alone in the field next to our house in that Casper costume, and that image – a boy in a Casper costume in a field – stayed with me.

CH: What you describe sounds like an incredibly organic way for a story to develop, allowing time for its true form to emerge. However, I’ve found that with success, the time I once had to dedicate to this organic process – which I prefer for both creative and aesthetic reasons – often gives way to deadlines and the ever-shifting Hollywood zeitgeist. What about you? Do you still maintain notebooks filled with potential script ideas waiting to coalesce into another A Perfect World?