In November 2009, the Nutty Putty Cave in Utah became the site of a tragic accident that captured international attention: the entrapment and subsequent death of John Edward Jones. As someone who was personally involved in the rescue efforts, arriving on the scene as efforts to free him reached a critical stage, I aim to provide a comprehensive account of what transpired. This detailed report, written from my perspective as a caver and rescuer, seeks to offer insight into the events surrounding this heartbreaking incident, particularly for those who have become interested due to recent viral videos and renewed media attention.

This account is based on my firsthand experience during the rescue attempt. For a broader understanding, I highly recommend reading Lindsay Whitehurst’s in-depth two-part article in the Salt Lake Tribune, which provides a well-rounded perspective. Lindsay Whitehurst’s two-part Salt Lake Tribune

Please be advised: The following report contains descriptions of John Jones’ condition, his passing, and related details which some readers may find disturbing. In respect for John and his family, I have strived to maintain sensitivity while accurately depicting the challenges faced during the rescue operation.

Nutty Putty Cave Rescue: A First-Hand Report

Originally Written for SAR on November 25, 2009

My involvement began with a call around 9:00 or 10:00 AM on Thanksgiving eve, 2009. Spencer Christian and Rodney Mulder contacted me, informing me of a rescue operation underway at Nutty Putty Cave. They inquired about my availability to assist. Initially, based on the information I gathered, it seemed there was already a sufficient number of personnel on site. I informed Spencer and Rodney that I would be available if the situation prolonged, exhaustion set in, and my assistance became absolutely necessary.

Approximately five hours later, Spencer called again, requesting my presence. He indicated that the team was tiring and that smaller cavers were urgently needed. I departed from work around 4:00 PM, quickly stopped home to collect my caving equipment, and proceeded to Nutty Putty Cave. I arrived at approximately 6:00 PM and was assigned to the next group entering the cave around 6:30 PM.

Upon reaching the main passage at the entrance of the Birth Canal, I observed teams working on a 4-to-1 haul system that had been established. I assisted with this system for about five minutes. However, it became apparent that the system was not effectively moving John Jones (1), and the team working directly with him required relief. Consequently, the cavers who had been attending to John exited the passage to rest.

During their exit, I spoke with Andy Armstrong. I inquired about John’s condition. Andy conveyed a concerning update: John was rapidly deteriorating, drifting in and out of consciousness, and had begun experiencing hallucinations, speaking of angels and demons.

Following this update, it was decided that I would proceed into the passage first to assess the situation and explore potential extraction strategies. Debbie would follow to interact with John, as she had already established a rapport with him and it was believed he might find comfort in her presence.

I entered the narrow passage. Immediately beyond the main passage, leading to John’s location, lies an extremely constricted crawl. This section is approximately 18 inches wide and 8 to 10 inches high, requiring a sharp 90 to 120-degree turn, which must be navigated feet first. Careful maneuvering is essential, as visibility of foot placement is limited until past the tightest point. As I carefully wormed my way into this restriction, my feet made contact with something soft—John’s feet. I felt movement, immediately lifted my feet, and shifted horizontally into the fissure.

John’s feet were situated about six feet beyond the constriction. I managed to position myself beside him, descending into the four-foot-wide fissure. After securing myself by wedging my body into a narrower part of the crack, I began speaking to John, introducing myself and asking about his well-being. There was no response. I adjusted my position slightly and tapped his leg. I could hear his breathing, characterized by deep, gurgling gasps, suggestive of fluid in his lungs. His feet then shifted in what appeared to be a frantic attempt to dislodge his legs from the entrapment. After a brief struggle, he ceased movement and seemed to lose consciousness (2). I continued to tap his legs and hip, attempting to elicit a response, but received none.

From this vantage point, I spent several minutes carefully examining the passage, John’s positioning, and the existing rigging setup to determine possible extraction methods. The situation appeared dire. I questioned the feasibility of moving him further. We could persist with the current rigging, but it seemed that his upward movement was limited to perhaps a foot or two in his current position, due to the webbing anchored around his knees. Beyond that, his feet would encounter the ceiling of the passage. Once his feet reached the ceiling, there was no mechanism to rotate him into a horizontal position. He would have to do that himself, but he was now unconscious. Even if horizontal positioning were achieved, he would still face the most challenging sections of the passage where he initially became trapped. Had he been conscious and at full strength, a slight chance of self-extraction might have existed. However, even under those ideal circumstances, the prospect seemed bleak. Even for me, weighing only 125 pounds, egress was exceedingly difficult. At the sharp bend within the constriction, I had to employ considerable contortion to navigate through. Extracting a 210-pound unconscious individual appeared virtually impossible.

The alternative strategy I considered was utilizing a jackhammer to widen the crack around him. This would involve removing several rock protrusions and enlarging the tightest constrictions, enabling a straight upward pull. This method would likely result in severe lacerations and potential fractures, but if all else failed, it seemed like the most viable option.

Between my exit from the passage and Debbie’s entry, a request was made to bring a radio to John so his family could speak to him. I believe his father, mother, and wife each spoke to him, expressing their love, prayers, and his father conveying a blessing. His wife spoke of a sense of peace, reassurance that everything would be alright. This communication lasted approximately 5 to 10 minutes, after which I indicated that we needed to resume efforts to free him.

At this juncture, I exited the passage to allow Debbie to attempt to squeeze past and assess the situation. However, upon reaching the tight constriction, she experienced severe leg cramps and was unable to proceed further. It was then that I decided to proceed with the jackhammer approach. We waited for the equipment to be brought to our location, and I then carried it down to John’s position. The tool was significantly heavier than anticipated, and supporting its weight while wedged in the narrow crack required maximal exertion. Furthermore, achieving an effective angle against the rock was challenging due to the confined space and my limited mobility. I attempted three strikes at a small lip of rock just below John’s foot. However, due to the angle, the hammer bit repeatedly slipped into the sandy sediment beside the rock lip. I tried repositioning myself, but in every other position, the length of the jackhammer, approximately 3 to 4 feet, became unmanageable within the confined space. I only had about 2.5 feet of clearance between myself and the target rock. Holding the jackhammer in such an awkward position rapidly depleted my strength.

I then requested a smaller tool, but none seemed available. Even if a smaller hammer drill were accessible, I doubted its effectiveness against the solid limestone walls. We then retreated to the Birth Canal to convene and reassess our strategy.

By this point, it was reported that the drills were malfunctioning or experiencing other issues. The only remaining drilling option was to use a compressed air hammer. It took about an hour to get the air hose routed down to our location. While waiting, we decided to shift tactics, attempting to widen the passage from above, working downwards towards John, rather than trying to widen the area directly around him. Once the compressed air drill arrived, Debbie, Max, and I spent about 90 minutes chipping away at the passage ceiling and floor, roughly 7 to 9 feet away from John’s position, above the primary constriction. Softer rock sections were relatively easy to remove. However, the harder limestone formations required immense effort. The main impediment was the extremely limited space, making it difficult to strike the rock at an optimal angle. Instead of effectively chipping off the rock knob, the drill often bored straight into the floor.

After 90 minutes of work, we had managed to remove only an 18” x 4” section of rock from the ceiling and floor. This was in a slightly wider section of the passage. Beyond this point, the cave narrowed further. In the most constricted segments, even lying flat and weighing only 125 pounds, the vertical clearance was a mere 3 to 6 inches. This was hardly conducive to maneuvering a jackhammer or even achieving an efficient working angle. To continue this excavation process, or even if we were to switch to micro-blasters, my estimation was that it would take anywhere from three to seven days to reach John’s location. Consequently, we regrouped once more to determine the subsequent course of action.

By now, it was nearing midnight. We were instructed to check John’s vital signs. A smaller paramedic was dispatched to assess whether he could reach John. In case the paramedic could not fit, he instructed me on using a stethoscope and thermometer, and how to locate a pulse. At 11:30 PM, we departed from the group at the Birth Canal and proceeded back down the passage. It took approximately 15 minutes to reach John. I went first, in case the paramedic could not fit through the tight sections. I initially attempted to use the stethoscope, but could only insert it about 3 inches upwards and to the right of his navel. I did not detect a distinct heartbeat, only rustling, fluttering sounds, likely caused by my own tremors as I struggled to maintain stability in an awkward position. I then wedged my hand between the rock and pressed as far up his torso as possible to feel for respiration. I did not believe I detected any breathing, but again, it was difficult to ascertain definitively due to my own shaking. His chest, where it pressed against the rock, felt warmer and sweaty, while the rest of his body temperature was close to the ambient rock temperature. I then removed his shoe and attempted to take his temperature. The thermometer displayed no reading, which the paramedic indicated was due to the temperature being below the instrument’s measurement range. As I removed his shoes and manipulated his feet, I noted that his feet and legs were significantly stiffer than earlier, and it was difficult to move his leg more than a few inches.

I relayed my findings to the paramedic above, and then crawled out to allow him to attempt to squeeze through. He managed to reach a position where he could feel John’s feet and confirmed that he had passed away. John Edward Jones was pronounced dead at 11:52 PM, as I recall.

At this point, we decided to return to the surface for a debriefing to discuss the plan moving forward. As everyone else began to exit the cave, the paramedic and I returned to John’s location to document the passage and his position with photographs.

With John’s passing, the complexity of body removal escalated exponentially. His body, now undergoing rigor mortis, would be unable to navigate the tight constriction above his feet without substantial passage modification, potentially requiring days or weeks of work with a hammer drill, or possibly faster with micro-blasters. Any bodily swelling would further impede extraction from the crack he was wedged in until the swelling subsided. There was no way to securely attach a rope to his body except at his feet. After several days, handling the body would necessitate hazmat suits and respirators for rescuers, significantly increasing the risk of heat exhaustion. In standard caving gear—pants and a short-sleeved shirt—a rescuer typically becomes drenched in sweat within 10 to 15 minutes and can work for 30 to 60 minutes before requiring a break. In a hazmat suit and respirator, effective work duration would likely diminish to 5 to 10 minutes before needing rest, in addition to severely restricted mobility. The prospect of body recovery appeared exceedingly grim (3).

Post-Incident Analysis

- The 4-to-1 haul system failed due to the convoluted passage between the hauling team’s location and John’s position. The numerous twists and turns induced so much friction, even with pulleys, that the system became ineffective.

- This moment likely marks the time of John’s death.

- The decision was ultimately made that attempting body removal posed excessive risk to rescuers. Nutty Putty Cave remains John Jones’ final resting place to this day.

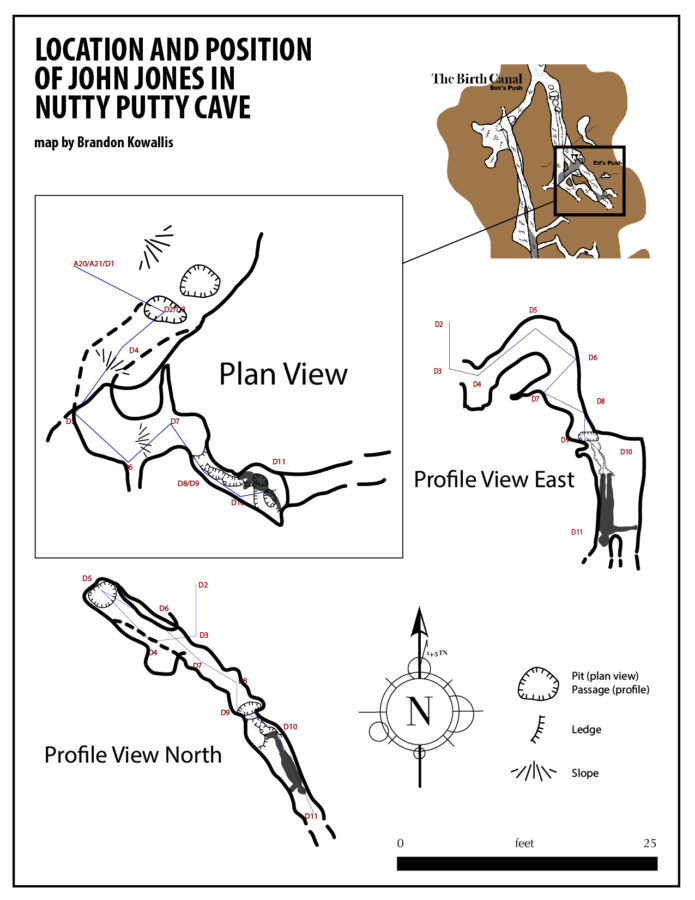

Below is a rescue map I created after the incident. Jon Jasper, Spencer Christian, Chuck Acklin, and I surveyed the cave in 2003, including the passage where John Jones became trapped. I utilized this survey data to generate profile views illustrating his entrapment location and position. I have also included rescue photos to provide a visual context of the area.

Nutty Putty Rescue Map

Nutty Putty Rescue Map

Rescue Site Photos

Rescuers at Nutty Putty Entrance

Rescuers at Nutty Putty Entrance

Paramedic Legs in Nutty Putty Passage

Paramedic Legs in Nutty Putty Passage

Caver Demonstrating Passage Tightness

Caver Demonstrating Passage Tightness

Paramedic Feet View in Nutty Putty Cave

Paramedic Feet View in Nutty Putty Cave

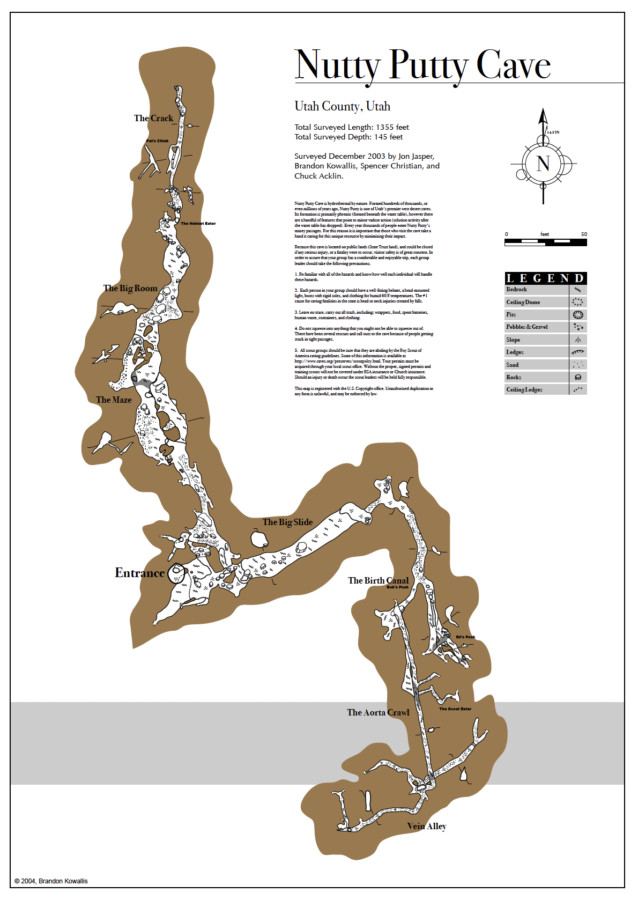

Nutty Putty Cave Map

Here is the complete cave map I drafted in 2003. John Jones was trapped not in the Birth Canal itself, but in the Ed’s Push area, which is accessed via the Birth Canal. A high-resolution PDF of this map is available for personal use at Cave Maps.

Nutty Putty Cave Full Map

Nutty Putty Cave Full Map

3D Animation of John Jones Entrapment Area

This animation, created using our survey data, offers a scale model of the section of Nutty Putty Cave where John Jones was trapped. While not as precise as a lidar scan, it is the most accurate visual representation available and helps to understand the spatial challenges faced during the rescue.

Nutty Putty Cave Entrance Today

A brief video captured recently showing the current entrance of Nutty Putty Cave:

Salt Lake Tribune Recent Coverage

The Salt Lake Tribune recently published an interview with me concerning the Nutty Putty Cave incident. The accompanying article can be found here: 15 years after a man died in the Nutty Putty Cave, his family and rescuers still struggle to escape the darkness.

Navigating Tight Cave Passages

To illustrate the challenges of navigating tight cave passages, here are two videos from a survey of a desert cave in Utah. The first video shows Mitch attempting a difficult downward squeeze, and the second shows me exiting a narrow passage that turned out to be a dead end. These videos demonstrate the reality of tight spaces in caving, which can be both challenging and, for experienced cavers, engaging.

A Note on Comments:

Thank you for your kind words and questions in the comments section. Due to time constraints related to family, work, and other commitments, I am unable to respond to all inquiries at this time (as of 9/27/24). Please review existing comments for previously answered questions and focus on asking new, non-speculative questions related to my direct involvement. All family-friendly comments will be approved, though there may be a delay of up to a week.

Future updates, such as videos, will be announced via my mailing list. You can subscribe on this page. You can also follow my YouTube channel for notifications of new content.

Thank you again for your understanding and kind words.