Colson Whitehead’s “John Henry Days” isn’t just a novel; it’s a vibrant, multifaceted re-singing of the quintessential American folk ballad, the “John Henry Song.” This exploration of the song, woven throughout the narrative, reveals its vastness and its capacity to reflect the very fabric of the United States. By examining how Whitehead incorporates and reimagines the “john henry song” in his work, we uncover layers of meaning about American identity, history, and the enduring power of myth.

The Lone Songwriter and the Genesis of a Song

Whitehead begins by introducing the archetypal “Lone Songwriter,” a figure musing under a tree, embodying the genesis of folk music. This solitary individual, contemplating the vast “country of songs,” highlights the organic, evolving nature of musical tradition. The songwriter’s act of capturing a melody, “almost stealing the song today,” mirrors the way folk songs are passed down, transformed, and personalized through generations. This initial image sets the stage for the book’s central theme: the “john henry song” as a living, breathing entity, constantly being reinterpreted.

Jake Rose: Plugging the Song in Tin Pan Alley

The character of Jake Rose, a song plugger in 1905 Bowery, New York, provides a contrasting perspective on song creation. Rose, recruited from a synagogue choir, represents the commercialization of music. His struggles to write songs in cramped cubicles, muffling his piano with newspapers to prevent theft, illustrate the competitive, industrialized music scene of the early 20th century. Rose’s efforts to write and sell a “john henry song” highlight another layer of the ballad’s journey – its transition from folklore to commodity.

Moses: Blues Rendition and the Weight of Destiny

Moving to 1930s Chicago, we encounter Moses, a Mississippi blues singer. Moses’s story delves into the emotional core of the “john henry song.” He grapples with capturing the essence of John Henry’s fateful choice, focusing on “what the man felt waking up in his bed the day of the race. Knowing what he had to do and knowing that it was his last sunrise…” Whitehead emphasizes the universality of John Henry’s predicament, stating “Moses certainly understood: that little terror on waking, for half a second, am I going to die today. Am I already dead?” Moses’s blues interpretation of the “john henry song” underscores its themes of mortality, determination, and the human condition.

Andrew Goodman: Echoes of Civil Rights and Enduring Struggles

The narrative subtly introduces Andrew Goodman, a record man in Chicago, and later draws a parallel to the Civil Rights worker Andrew Goodman, murdered in Mississippi in 1964. This connection layers the “john henry song” with the weight of American racial history. The phrase “It’s always Mississippi in the fifties,” repeated in the book, emphasizes the cyclical nature of racial injustice. This reference to the Civil Rights era transforms the “john henry song” into a lament for racial inequality and a reminder of ongoing struggles for justice.

FBI 1964 file photo of bodies of murdered civil rights workers uncovered from dam in Mississippi

FBI 1964 file photo of bodies of murdered civil rights workers uncovered from dam in Mississippi

FBI 1964 file photo of the unearthed bodies of civil rights activists James Chaney, Andrew Goodman, and Michael Schwerner, evidence in the Edgar Ray Killen trial.

The Statue Maker and Pamela Street: Tangible and Intangible Legacies

The statue maker, tasked with visualizing John Henry, embodies another form of interpretation. He relies on the “footprint left in his psyche” by the legend, highlighting the subjective and imaginative nature of myth-making. Pamela Street, daughter of a John Henry obsessive, offers a contrasting, personal perspective. Her father’s collection, a “John Henry Museum” in their Harlem apartment, becomes a burden, representing the potentially suffocating weight of legend. Pamela’s story of the statue being vandalized – “One time they chained the statue to a pick-up and dragged it off the pedestal down the road there” – becomes a powerful metaphor for the song’s journey through culture, subject to misinterpretation and even violence.

John Henry statue in Talcott, WV, USA, symbolizing the enduring legend

John Henry statue in Talcott, WV, USA, symbolizing the enduring legend

The John Henry statue in Talcott, West Virginia, a landmark commemorating the legendary steel-driving man.

“Guitar Drag” and the Un-Singing of a Ballad

The act of dragging the John Henry statue is directly linked to the horrific murder of James Byrd, Jr., in Jasper, Texas. This connection is further emphasized through Christian Marclay’s “Guitar Drag,” a video piece where an electric guitar is dragged behind a truck. This unsettling work becomes an “un-singing” of the “john henry song,” a visceral representation of racial violence and the brutal realities that undermine the ballad’s heroic narrative. Marclay’s work reframes the “john henry song” as a counterpoint to the unspeakable acts of racial hatred in America.

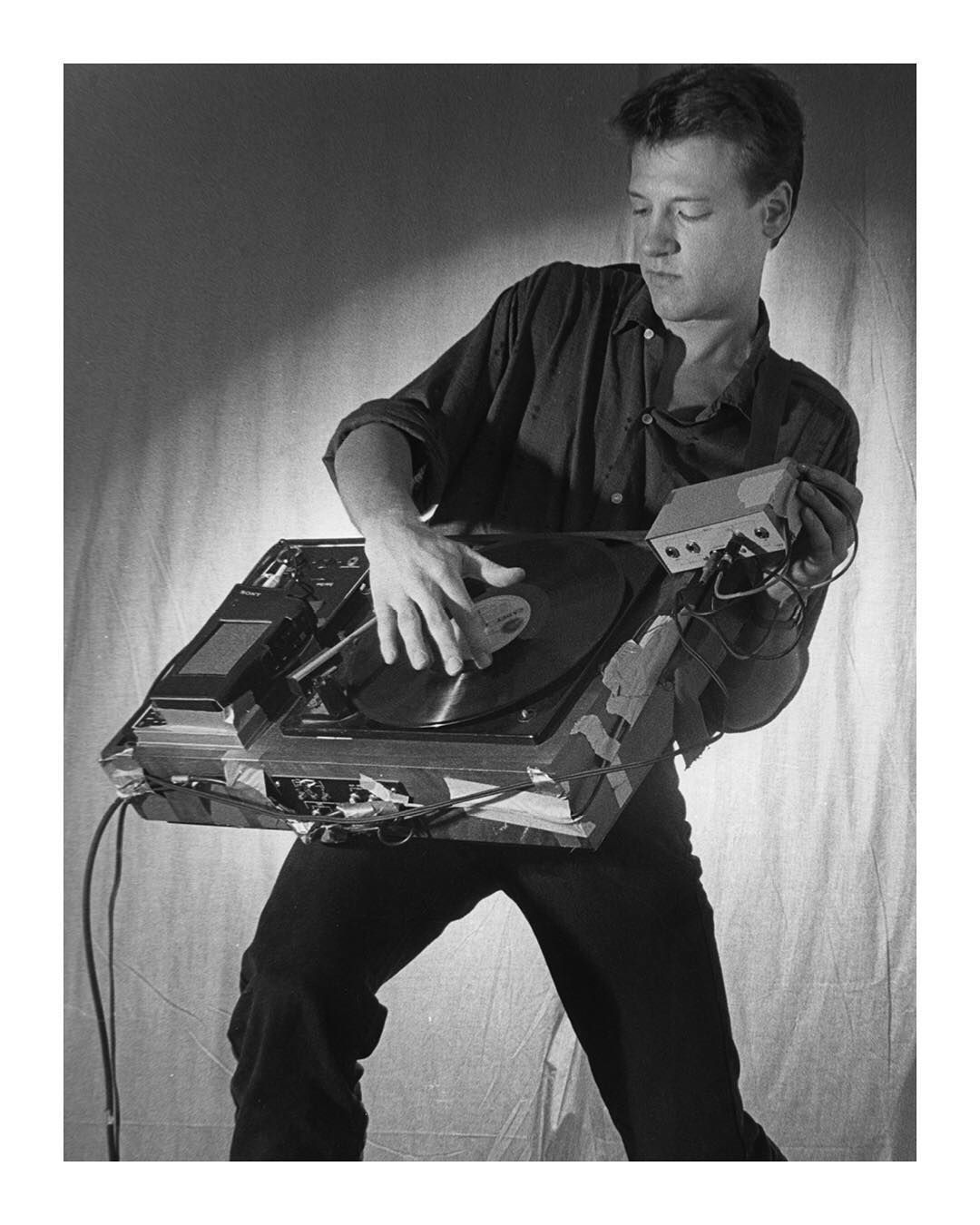

Christian Marclay in performance with phonoguitar in the 1980s new wave art scene

Christian Marclay in performance with phonoguitar in the 1980s new wave art scene

Christian Marclay performing with his phonoguitar in New York City’s vibrant 1980s art and music scene.

Christian Marclay's "Guitar Drag" artwork installation, exploring sound and historical recontextualization

Christian Marclay's "Guitar Drag" artwork installation, exploring sound and historical recontextualization

Installation view of Christian Marclay’s “Guitar Drag” at Mudam Luxembourg, a powerful exploration of sound and cultural memory.

Jennifer Sutter and the Song’s Resonant Power

Jennifer Sutter, a young girl in 1950s Harlem, discovers a piece of water-damaged sheet music for the “john henry song.” Despite her mother’s disapproval, Jennifer is captivated by the song. Drawing on Constance Rourke’s theories of American archetypes, Whitehead suggests that even through the minstrel tradition, “something real, some true speech, the straining voice of the back American speaking out of the mouth of the white American” emerges. For Jennifer, the “john henry song” is not just a melody but a force that “pushes her… it quickens inside her,” demonstrating the song’s enduring emotional resonance across generations and experiences.

Alphonse Miggs: A Twisted Embodiment of the Legend

Alphonse Miggs, a stamp collector obsessed with railroads, embodies a distorted version of John Henry. His violent outburst at the John Henry stamp unveiling, where he “pull out his pistol and start shooting,” suggests a warped identification with the legendary figure. Miggs, as the “leader of the Alphonse Miggs Liberation Front,” becomes a bizarre, almost tragicomic, representation of the song’s themes of struggle and rebellion, taken to an extreme.

The Crackhead Singer: Raw Expression and the Song’s Persistence

In a New York bodega, a crackhead accosts J., offering to “sing for my supper.” His raw, desperate rendition of “This old hammer killed John Henry but it won’t kill me!” is a stark and unexpected iteration of the “john henry song.” This encounter highlights the song’s persistence in unexpected places and its ability to be reinterpreted in the most marginalized voices. J.’s act of giving him money, declaring “You won,” ironically casts the crackhead as John Henry, pitted against the “steam drill” of societal power and economic hardship.

Mr. Street’s Museum: Obsession and the Unbeaten Foe

Mr. Street, Pamela’s father, dedicates his life to his John Henry Museum, a testament to his consuming obsession. He meticulously curates his collection, playing different versions of the “john henry song” across various media, “following the song as technology chases it.” In the end, Mr. Street becomes a tragic figure, waiting for crowds that never come. He embodies John Henry in his unwavering devotion, but in a poignant reversal, the “legend of John Henry itself—or the forgetting of the legend” becomes the “steam drill he can never beat.” For Mr. Street, John Henry transforms into the insurmountable mountain, a poignant commentary on the consuming nature of obsession and the elusiveness of legacy.

John Henry Himself: Myth Made Flesh

Throughout the novel, glimpses of John Henry’s life emerge, revealing his origins as a slave leased to the mines at a young age. Even as a character, John Henry remains “spectral,” more a figment of legend than a fully fleshed-out individual. His nightmare, where the mountain turns to flesh and rivers of blood flow, underscores the brutal reality behind the myth. However, in describing John Henry’s internal experience – “He had traveled through a series of fever dreams all night. They were coupled together like train cars…”—Whitehead captures the essence of storytelling itself, equating the act of writing with the creation of a song, a powerful and resonant image.

Pamela’s Song and the Enduring Versions

In the novel’s closing moments, Pamela, scattering her father’s ashes, sings the “john henry song” under her breath, a personal and intimate rendition. She recognizes the multiplicity of the ballad, acknowledging “there are many versions of the song, as many versions as there are people who sing it.” This final act of singing encapsulates the central theme: the “john henry song” is not static but a constantly evolving narrative, shaped by individual voices and collective memory.

Conclusion: The Unending Ballad of America

“John Henry Days” brilliantly utilizes the “john henry song” as a lens through which to examine American identity, history, and the enduring power of myth. Through a diverse cast of characters and interwoven narratives, Whitehead demonstrates how the song is constantly “re-sung,” each iteration adding new layers of meaning and reflecting the complexities of the American experience. From the lone songwriter to Mr. Street’s museum, the novel reveals the ballad’s remarkable capacity to absorb and reflect the nation’s triumphs and tragedies, ensuring that the “john henry song” remains a vital and evolving part of the American cultural landscape.