The quotes from renowned directors at the beginning of the original article effectively highlight John Ford’s immense stature in cinema. Let’s keep them to start the new article with impact.

“John Ford is really great…When I’m old, that’s the kind of director I want to be.” – Akira Kurosawa

“Ford – I esteem him, I admire him and I love him.” – Federico Fellini

“He is the essence of classical American cinema. Any serious person making films today, whether they know it or not, is affected by Ford.” – Martin Scorsese

“I like the old masters, by which I mean John Ford, John Ford, and John Ford.” – Orson Welles

For many, the name John Ford conjures images of sweeping Western landscapes and iconic figures like John Wayne. However, to truly understand John Ford‘s monumental contribution to cinema, one must delve far beyond the genre he’s most associated with. The sheer scope of his filmography is staggering. As noted by a commenter on a blog post lamenting the focus on European arthouse directors, exploring John Ford‘s work is no small undertaking. With 146 directing credits listed on IMDb, including shorts and documentaries, and around 80 films remaining after accounting for lost works, a comprehensive retrospective requires considerable dedication.

Instead of merely focusing on the universally acclaimed “classics,” a deeper exploration of John Ford‘s oeuvre reveals hidden gems and unexpected insights. Consider Howard Hawks’ Today We Live, a film often overlooked but personally cherished by the author for its engaging narrative. Limiting oneself to only the celebrated works risks missing out on such discoveries and a fuller appreciation of a director’s range and evolution.

Driven by this spirit of comprehensive exploration, a journey through John Ford‘s entire filmography, from his debut feature Straight Shooting (1917) to 7 Women (1966), was undertaken. The unfortunate loss of numerous films, particularly from his early period at Fox during the 1910s and 1920s (due to a significant vault fire in 1937), leaves unavoidable gaps, including his first sound film, the short Napoleon’s Barber.

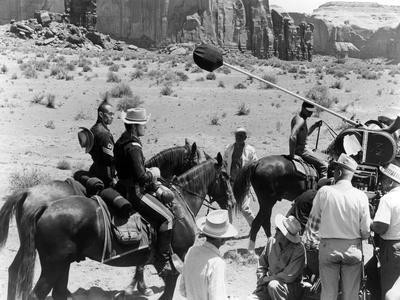

John Ford directing a film

John Ford directing a film

Unpacking the Oeuvre of John Ford: Key Themes and Ideas

Having immersed oneself in such a vast body of work, the question arises: what unifying threads, if any, connect the diverse films of John Ford? While a single, all-encompassing theory might be elusive given the breadth and depth of his filmography, several recurring ideas emerge as central to understanding his cinematic vision.

John Ford was, first and foremost, a studio director. His early career was shaped by Universal, followed by a significant period with Fox. From 1917 to 1966, he maintained an astonishing output of approximately three films per year. The only major interruption was his service with the OSS and Navy during World War II (1941-1945), where he shifted from commercial filmmaking to wartime endeavors.

This studio system context contributed to the remarkable variety within his filmography. Unlike directors known for thematic or stylistic repetition, John Ford embraced diverse genres. While Westerns are his hallmark, he also ventured into comedies, romances, family sagas, war films, historical dramas, and even art house cinema. This eclecticism makes identifying a singular, overarching theme challenging.

However, through careful examination, a constellation of interconnected ideas surfaces throughout John Ford‘s work. These core themes, arguably, are: duty, male camaraderie, and Irish identity.

Duty: Service and Sacrifice in Ford’s Films

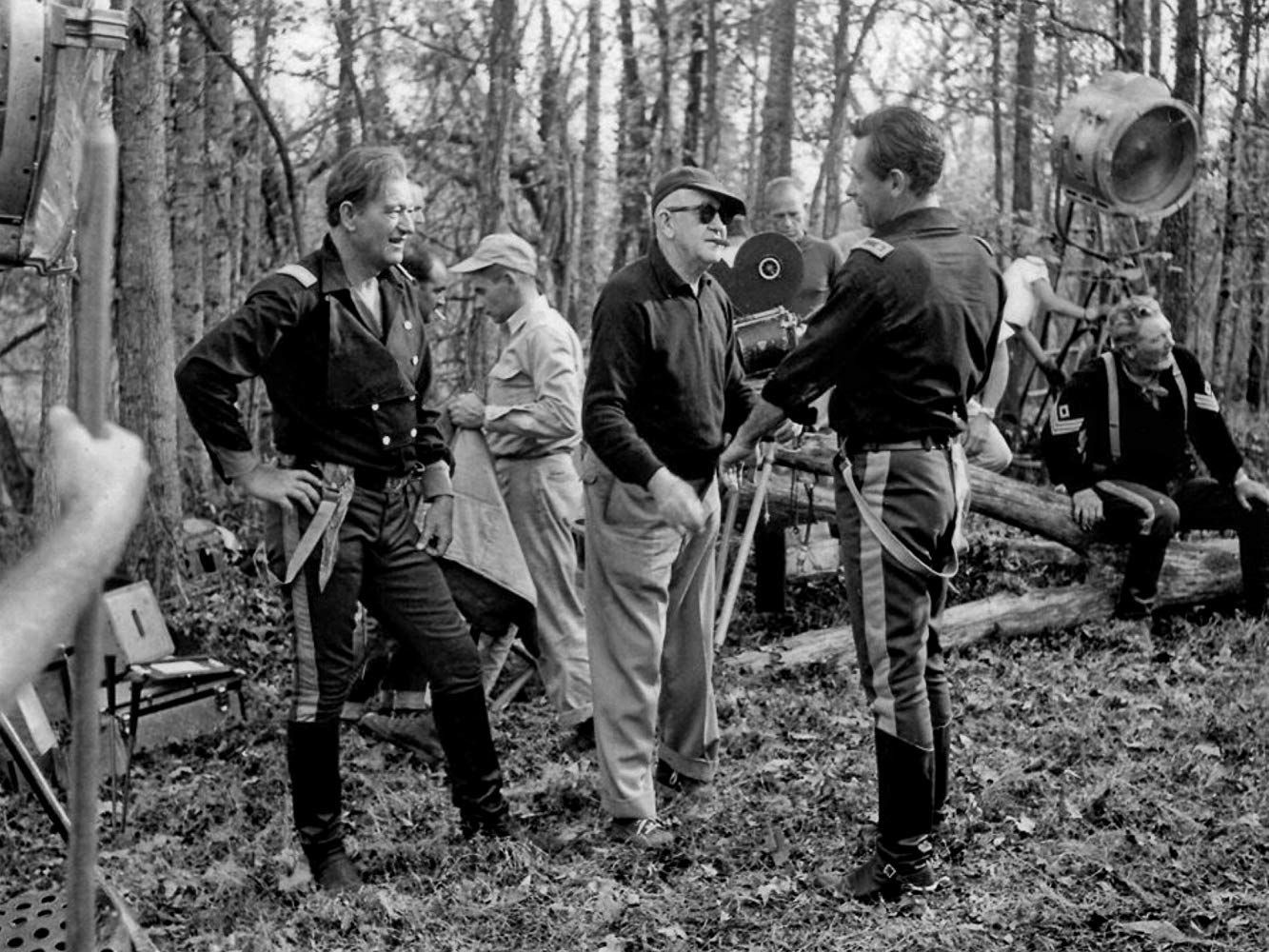

John Ford with Woody Strode and Jeffrey Hunter on set

John Ford with Woody Strode and Jeffrey Hunter on set

The concept of duty resonates powerfully in John Ford‘s military films. From the poignant reflection on wartime mortality in They Were Expendable to the exploration of cavalry life in Rio Grande, his characters grapple with multifaceted obligations. These include duty to country, military branch, unit, and, crucially, to fellow soldiers. The latter aspect often intertwines with male camaraderie, but duty remains a distinct and significant motif.

The Wings of Eagles, a biographical film about Frank “Spig” Wead, epitomizes this theme. Wead’s unwavering commitment to his nation and the Navy, even after a debilitating accident, clashes with his marital duty. His ultimate choice underscores the primacy of his broader sense of obligation.

This exploration of duty extends beyond explicitly military settings, appearing in films like Men Without Women and Seas Beneath. Submarine Patrol, often unjustly overlooked, stands out as a compelling early example of this thematic preoccupation.

Male Camaraderie: Bonds Forged in Adversity

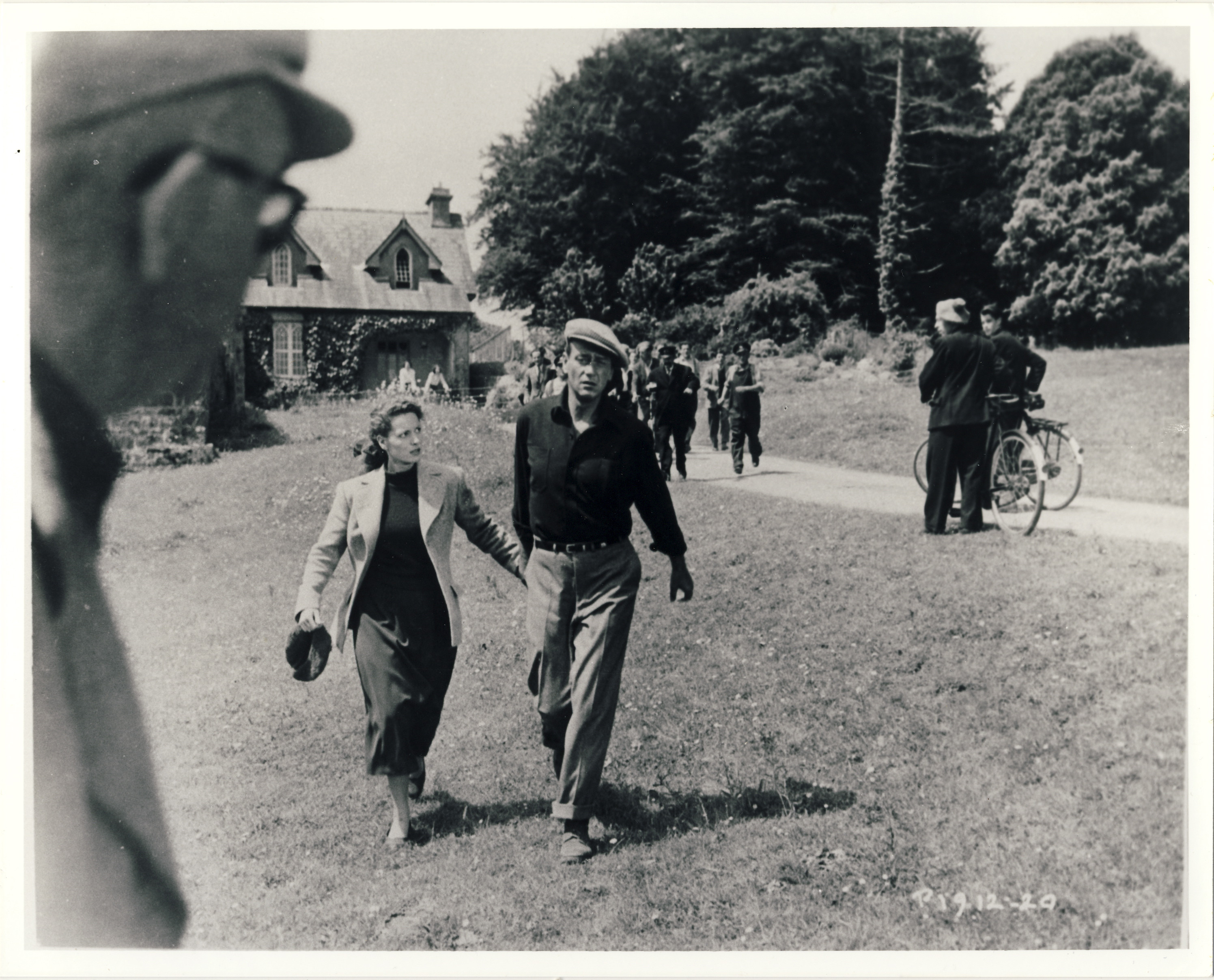

Men together, showcasing male camaraderie in a John Ford film

Men together, showcasing male camaraderie in a John Ford film

Male camaraderie is perhaps the most pervasive theme in John Ford‘s cinema. It permeates genres, from military adventures and Westerns to immigrant narratives. This motif is evident in both his celebrated masterpieces and lesser-known works. From The Searchers to Two Rode Together, and spanning decades from Hell Bent (1918) to Donovan’s Reef (1963), the dynamics between men are fundamental to his storytelling.

While sharing similarities with Howard Hawks’ portrayal of male characters, Ford‘s approach diverges in a crucial aspect. Hawks often employed love triangles, pitting men against each other in romantic competition. In Ford‘s films, women, while present, are frequently secondary to the bonds between men. These male relationships are not contingent on romantic interests; they are independent and inherently valuable. They offer unique support systems rooted in shared masculine experiences, yet are also marked by inherent tensions and rivalries.

The Lost Patrol poignantly depicts the strains and resilience of male bonds within a WWI British unit facing desert hardship, enemy threats, and death. 3 Bad Men illustrates the self-sacrificing nature of brotherhood as three outlaws unite to protect a young woman. The Long Voyage Home explores the fragile yet vital camaraderie of merchant seamen during the early days of WWII, where external fears threaten to fracture their internal solidarity.

Countless other John Ford films echo this theme: The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, the Cavalry Trilogy, Sergeant Rutledge, Up the River, Air Mail, 3 Godfathers, and Four Sons, among many others. Ford‘s films often depict men in traditionally masculine professions and perilous environments, finding solace and strength in their bonds with one another. Beneath the rugged exterior, a deep appreciation for these connections reveals a more sentimental side to John Ford‘s directorial vision.

The Irish Identity: Heritage and Homeland

Scene from The Quiet Man, showcasing Irish setting

Scene from The Quiet Man, showcasing Irish setting

Born John Martin Feeney in Maine to Irish immigrants, John Ford’s Irish identity profoundly influenced his life and work. This heritage is palpable even in his silent films. The Shamrock Handicap celebrates the Irish immigrant experience and the supportive communities that facilitated the American dream. While he broadened this immigrant narrative to include other groups, such as Bavarians in Flesh and Four Sons, his primary focus, particularly as he gained creative control, remained on his Irish roots.

Early Ford films, including the partially lost Mother Machree and The Informer, utilize the allure of America as a central plot device and character motivation. America is portrayed as a sanctuary from the oppression of British rule, an idealized haven offering new beginnings. The Informer, set in Dublin, depicts a protagonist seeking passage to America after becoming ostracized for his actions during the Irish conflict.

Later in his career, even as John Ford became synonymous with Westerns, he continued to revisit Irish themes. The Quiet Man, perhaps his most famous Irish film, tells the story of an Irish-American returning to his ancestral home in Inisfree. The Rising of the Moon, an anthology film, presents three Irish stories set entirely in Ireland, devoid of the immigrant narrative. Ford‘s cinematic exploration of Irish identity evolved from the immigrant experience to a more nostalgic and romanticized portrayal of Ireland itself.

The Quintessential John Ford Film?

John Ford directing John Wayne, a classic image

John Ford directing John Wayne, a classic image

Given the vast and varied landscape of John Ford‘s filmography, pinpointing a single film that encapsulates his entire oeuvre is a complex task. Unlike directors with smaller, more thematically consistent bodies of work, Ford‘s prolific output and studio-driven career make a simple summation difficult.

While a definitive “John Ford movie” might be unattainable, The Quiet Man comes closest to embodying many of his key elements. It features Ireland, his most frequent leading man John Wayne, leading lady Maureen O’Hara, and a host of familiar supporting players. Horses, a recurring motif from his Westerns and silent films like Kentucky Pride and The Shamrock Handicap, also appear. Furthermore, the film explores male camaraderie through the memorable boxing match between Wayne’s character and his brother-in-law.

However, The Quiet Man also deviates from some typical Fordian traits. Its vibrant color palette, while Oscar-winning, contrasts with the stark black and white cinematography often associated with his visual style, exemplified by The Informer, The Fugitive, The Long Voyage Home, and The Grapes of Wrath. The theme of duty, particularly military service, is less prominent, replaced by a focus on marital obligations. The romantic storyline also marks a slight departure from his more typical focus on male relationships.

Thus, The Quiet Man, while not a perfect representation, serves as a valuable lens through which to understand John Ford‘s multifaceted talent and enduring appeal. While The Searchers might be a personal favorite for some, The Quiet Man offers a broader spectrum of Ford‘s thematic and stylistic signatures.

Unearthing Hidden Gems: John Ford Recommendations

Poster for The Fugitive, a recommended John Ford film

Poster for The Fugitive, a recommended John Ford film

Beyond the celebrated classics, John Ford‘s filmography is rich with lesser-known works deserving wider recognition. Here are five recommendations for those seeking to explore the less-charted territories of his cinematic landscape:

- The Fugitive (1947): An artful adaptation of Graham Greene’s The Power and the Glory, starring Henry Fonda as a priest in a socialist-controlled Central American nation. A visually striking and deeply moving film, considered by some as a hidden masterpiece within Ford‘s oeuvre.

- Submarine Patrol (1938): Often overshadowed by Stagecoach, this WWI naval drama, starring Richard Greene, offers a compelling blend of submarine warfare and romance. A forgotten gem showcasing Ford‘s versatility.

- Hangman’s House (1928): A concise and engaging silent film set in Ireland, revolving around an outlawed Irish soldier seeking justice. A tight narrative and a rewarding entry point into Ford‘s silent era.

- The Informer (1935): Despite its accolades, including Oscars for Best Director and Best Actor (Victor McLaglen), The Informer is sometimes overlooked today. McLaglen delivers a career-defining performance as a guilt-ridden man in this visually stunning, German Expressionism-influenced film.

- The Plough and the Stars (1936): A passion project for Ford, this Irish-set film faced production challenges and studio interference. While not flawless, it remains a worthwhile watch, anchored by Barbara Stanwyck’s performance, despite her questionable Irish accent.

These five films offer a glimpse beyond the well-trodden paths of John Ford‘s filmography, revealing the depth and breadth of his cinematic artistry.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of John Ford

John Ford in his later years

John Ford in his later years

The exploration of John Ford‘s extensive filmography could extend into numerous other avenues. The recurring presence of his stock company of actors, the role of religion in his films, and his foundational contribution to cinematic visual language are all worthy of deeper analysis. Alongside D.W. Griffith, John Ford arguably shaped the fundamental vocabulary of popular filmmaking.

This retrospective journey through John Ford‘s work has been a rewarding endeavor. His films continue to resonate, prompting ongoing discussion and appreciation. As we conclude this exploration, perhaps a shift in focus is due – to the work of Mel Brooks, the husband of Anne Bancroft, the star of Ford‘s final film, 7 Women.