In 1994, a chance encounter with John Ehrlichman, a figure synonymous with the Watergate scandal, offered a chilling revelation that unlocked a dark secret in modern American history. As Richard Nixon’s domestic policy chief, Ehrlichman held a pivotal role in shaping the nation’s trajectory, and his candid confession illuminated the deeply cynical origins of the United States’ policy of drug prohibition. This policy, initiated under Nixon’s “war on drugs,” continues to inflict widespread misery and yield remarkably few positive outcomes, even decades later. Americans had been enacting laws against psychoactive substances since the late 19th century, starting with San Francisco’s 1875 anti-opium ordinance. However, it was under Nixon’s administration that this criminalization escalated into a full-fledged “war,” setting the nation on its current path of punitive measures and counterproductive strategies.

A patient drinks a dose of methadone at the Taipas rehabilitation clinic in Lisbon, Portugal © Rafael Marchante/Reuters

A patient drinks a dose of methadone at the Taipas rehabilitation clinic in Lisbon, Portugal © Rafael Marchante/Reuters

The Confession: Ehrlichman’s Blunt Revelation

My pursuit of John Ehrlichman led me to an engineering firm in Atlanta, where he was engaged in minority recruitment. The man I met was a far cry from the stern, composed figure of the Watergate era. He had gained considerable weight and sported a substantial beard, a stark contrast to his clean-cut image from two decades prior. I was then deeply immersed in researching the political underpinnings of drug prohibition, intending to write a book on the subject. I approached Ehrlichman with earnest, policy-oriented questions, seeking to understand the historical and political context of the “war on drugs.”

However, Ehrlichman dismissed my academic inquiries with a wave of impatience. “You want to know what this was really all about?” he asked, his tone imbued with the stark candor of a man seemingly liberated from the constraints of public image after disgrace and imprisonment. “The Nixon campaign in 1968, and the Nixon White House after that, had two enemies: the antiwar left and black people. You understand what I’m saying?” He paused, letting the weight of his words sink in. “We knew we couldn’t make it illegal to be either against the war or black, but by getting the public to associate the hippies with marijuana and blacks with heroin, and then criminalizing both heavily, we could disrupt those communities. We could arrest their leaders, raid their homes, break up their meetings, and vilify them night after night on the evening news. Did we know we were lying about the drugs? Of course we did.”

Ehrlichman’s blunt admission was delivered with shocking nonchalance. My visible shock was met with a mere shrug from him. He glanced at his watch, presented me with a signed copy of his spy novel, The Company, and then ushered me towards the door, the encounter abruptly concluded.

Nixon’s War on Drugs: A Legacy of Cynicism and Failure

Richard Nixon’s creation of the war on drugs was, as Ehrlichman revealed, a calculated political maneuver rooted in cynicism. However, this strategy, born from political expediency, has been perpetuated and expanded by every subsequent president, irrespective of party affiliation. Democrats and Republicans alike have found the drug war to be a convenient and potent political tool for various reasons over the decades. Meanwhile, the staggering costs of this “war” have become increasingly undeniable and impossible to ignore.

Billions of taxpayer dollars have been squandered in the name of drug control, with little to show for it in terms of reduced drug availability or use. The drug war has fueled immense bloodshed, not only in Latin America, where drug cartels wield immense power and violence, but also on the streets of American cities, ravaged by drug-related crime and gang violence. Millions of lives have been irrevocably damaged by draconian punishments that extend far beyond prison walls. The collateral damage is particularly pronounced within minority communities; alarmingly, one in eight black men in the United States has been disenfranchised due to a felony conviction, often stemming from drug-related offenses.

The High Cost of Prohibition: Societal Damage

The consequences of drug prohibition extend far beyond mere financial expenditure. The societal fabric is frayed by the relentless “war on drugs.” As H. L. Mencken astutely observed in 1949, Americans harbor “the haunting fear that someone, somewhere, may be happy,” a sentiment that perhaps underlies the nation’s seemingly inherent drive to criminalize behaviors and substances that alter mood or consciousness. This puritanical impulse to control personal experience clashes sharply with the reality of human desire for altered states.

The desire for altered states of consciousness is a fundamental aspect of human experience and inevitably creates a market. By attempting to suppress this market through prohibition, we have inadvertently fostered a dangerous underworld populated by “genuine bad guys” – the pushers, gang members, smugglers, and killers who thrive in the shadows of illegality. While addiction is undeniably a severe and distressing condition, it is statistically relatively rare. The vast majority of the harms associated with drugs – the violence, the overdoses, the pervasive criminality – are not inherent to the substances themselves, but rather are direct consequences of prohibition. Despite decades of relentless enforcement, even the Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) concedes that the drugs they are fighting against are becoming cheaper and more readily available, highlighting the abject failure of the current approach. Victory in this “war” remains an unattainable illusion.

Glimmers of Hope: Emerging Alternatives and Reform

Despite the entrenched nature of drug prohibition, a significant shift in perspective is beginning to emerge. For the first time in decades, there is a tangible opportunity to change course and explore alternatives to the harsh and ineffective policies of the past. Experiments in drug policy reform are gaining momentum both within the United States and internationally.

Within the U.S., twenty-three states, alongside the District of Columbia, have legalized medical marijuana, recognizing its therapeutic benefits. Furthermore, four states – Colorado, Washington, Oregon, and Alaska – and D.C., have taken the bolder step of legalizing recreational marijuana altogether. Several more states, including Arizona, California, Maine, Massachusetts, and Nevada, were poised to vote on similar legalization measures, indicating a growing public appetite for reform.

Internationally, Portugal has adopted a groundbreaking approach by decriminalizing not only marijuana but also cocaine, heroin, and all other drugs. This radical policy shift, implemented in 2001, provides a compelling case study in harm reduction and alternative drug management. Vermont has implemented programs allowing heroin addicts to access state-funded treatment instead of facing automatic incarceration. Canada initiated a pilot program in Vancouver in 2014 to provide pharmaceutical-grade heroin to addicts under medical supervision, mirroring similar programs in Switzerland. The Home Affairs Committee of Britain’s House of Commons has also recommended that the United Kingdom consider adopting similar strategies. Chile embarked on legislative efforts to legalize both medicinal and recreational marijuana use, including allowing home cultivation. Even Colombia, a nation long ravaged by the drug war, has begun to shift its stance. President Juan Manuel Santos, in December, acknowledged the failure of the forty-year “war on drugs” and subsequently legalized medical marijuana by decree. In a landmark ruling, the Mexican Supreme Court declared that the prohibition of marijuana consumption violated the Mexican Constitution, citing infringements on “personal sphere,” “right to dignity,” and “personal autonomy.” The Supreme Court of Brazil is considering a similar legal challenge, indicating a broader trend towards re-evaluating drug prohibition on constitutional and human rights grounds.

The Path Forward: From Prohibition to Regulation

The growing global conversation around drug policy reform points towards a fundamental shift in understanding. Depending on how the issue is framed, drug legalization can appeal to a surprisingly broad political spectrum. Conservatives, often wary of excessive government spending, overreaching state power, and infringements on individual liberty, may find common ground with legalization arguments. Liberals, equally concerned about police brutality, the devastating impact on Latin America, and the disproportionate criminalization of minority communities, also find compelling reasons to support reform.

Moving beyond the limited scope of marijuana legalization to consider ending all drug prohibitions will require political courage. However, this step may be less daunting than politicians currently perceive. Criticism of mandatory minimum sentences, mass arrests for marijuana possession, and police militarization has already become increasingly mainstream and politically acceptable. Even figures within the establishment, such as former Attorney General Eric Holder and Michael Botticelli, the former “drug czar,” have publicly questioned the excesses of the drug war. Few prominent voices in public life now actively defend the status quo with its demonstrable failures and devastating consequences.

This evolving global landscape sets the stage for critical discussions at the United Nations. The UN General Assembly convened for its first drug conference since 1998. The optimistic motto of the 1998 meeting, “A Drug-Free World — We Can Do It!” now rings hollow, starkly contrasted by the reality of the global drug situation. The UN now faces a world where those who have suffered most from the “war on drugs” have lost faith in the old, enforcement-heavy ideology. This shift was evident at the 2012 Summit of the Americas in Cartagena, Colombia, where Latin American leaders openly debated – much to the discomfort of then-President Obama – the potential benefits of legalizing and regulating drugs as a hemisphere-wide strategy.

The UN General Assembly must also confront the undeniable fact that four U.S. states and the nation’s capital have fully legalized marijuana. This domestic development directly undermines the U.S.’s role as the world’s most zealous drug enforcer. As a member of the UN’s International Narcotics Control Board noted, “We’re confronted now with the fact that the U.S. cannot enforce domestically what it promotes elsewhere.” Even William Brownfield, the State Department’s chief drug-control official, abruptly reversed his previous stance, acknowledging in 2014 that the “drug control conventions cannot be changed” was no longer tenable. He admitted, “How could I, a representative of the government of the United States of America, be intolerant of a government that permits any experimentation with legalization of marijuana if two of the fifty states of the United States of America have chosen to walk down that road?” This admission sent shockwaves through the drug-reform community, signaling a potential paradigm shift.

Learning from Experience: Portugal and Colorado

As the once-unthinkable prospect of ending the war on drugs comes into clearer view, the crucial conversation must shift from why to how. Realizing the potential benefits of ending drug prohibition will require more than simply declaring drugs legal. The transition poses significant risks. For example, deaths from heroin overdose in the United States surged by an alarming 500 percent between 2001 and 2014, while deaths from prescription opioids – already legal and regulated – increased by nearly 300 percent. These statistics underscore the complexity of opioid regulation, demonstrating failures in both prohibition and current regulatory frameworks. A significant increase in drug dependence or overdoses following legalization would be a public health catastrophe, potentially triggering a backlash and a return to counterproductive prohibitionist policies.

To mitigate harm and establish order, we must design significantly improved systems for licensing, standardizing, inspecting, distributing, and taxing currently illicit drugs. The path forward will involve navigating a myriad of complex choices, and initial attempts may not be perfect. Some aspects of public health and safety may improve, while others might initially worsen. However, we are not without precedent. We can draw valuable lessons from the end of alcohol Prohibition in the 1930s and from more recent experiences with drug policy reform both domestically and internationally. Ending drug prohibition is fundamentally a matter of imagination and effective management, two areas where American ingenuity and pragmatism can be effectively applied. We have the capacity to achieve this.

Let us begin by addressing a question that is too often overlooked: What precisely is our drug problem? It is not simply drug use itself. Alcohol consumption is widespread in the United States, yet only a relatively small percentage of drinkers develop alcoholism. Similarly, while the idea of casual heroin or methamphetamine use might seem inherently dangerous, the reality is that many individuals engage in occasional use without succumbing to addiction. Government data from the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) challenges the myth of “instantly addictive” drugs. Although approximately half of all Americans over the age of twelve have tried an illegal drug, only 20 percent of those have used one in the past month. Within this monthly-use group, cannabis is the most prevalent drug. Only a small fraction of individuals who have experimented with “hard” drugs like heroin, cocaine, crack, and methamphetamine have used them in the past month. (The figures are 8 percent for heroin, 4 percent for cocaine, 3 percent for crack, and 4 percent for meth.) It is even debatable whether monthly drug use necessarily constitutes a “drug problem.” The proportion of lifetime alcohol drinkers who develop alcoholism is around 8 percent, and monthly alcohol consumption is not typically equated with alcoholism.

In essence, the core drug problem – debilitating addiction – affects a relatively small segment of the population. Peter Reuter, a veteran drug-policy researcher at the University of Maryland, estimates that the number of people addicted to hard drugs in the U.S. is fewer than 4 million out of a population of 319 million. Addiction is a chronic illness characterized by relapses, similar to conditions like diabetes, gout, and hypertension. Drug dependence can inflict immense hardship on both the individual struggling with addiction and their loved ones. However, addressing addiction does not necessitate the current exorbitant expenditure of $40 billion annually on law enforcement, the mass incarceration of half a million people, and the erosion of civil liberties for all citizens, regardless of drug use.

It is conceivable that the relatively low number of hard drug addicts is, paradoxically, a consequence of drug prohibition. Mark Kleiman, a public policy professor at New York University and long-time critic of the war on drugs, posits that if cocaine were legalized, there is no guarantee that the rate of cocaine abuse would be lower than that of alcoholism, which affects approximately 17.6 million Americans. Furthermore, Kleiman suggests that legalizing cocaine might exacerbate both cocaine addiction and alcoholism, citing a potentially synergistic effect: “A limit to alcoholism is you fall asleep. Cocaine fixes that. And a limit to cocaine addiction is you can’t sleep. Alcohol fixes that.”

Kleiman’s prediction of a significant surge in addiction rates following legalization is intuitively plausible. Prudence and ethical considerations dictate that any drug legalization plan must proactively address the potential for increased dependence. Millions of individuals already struggling with addiction in the United States lack access to treatment. While drug treatment is demonstrably cost-effective – the government estimates a $7 return for every dollar invested – treatment and prevention initiatives receive only 45 percent of the federal drug budget, while enforcement and interdiction consume 55 percent, excluding the immense costs of incarceration. The Affordable Care Act, mandating insurance coverage for mental health services, including addiction treatment, at parity with physical illnesses, may improve treatment accessibility. However, training qualified treatment providers is a time-consuming and resource-intensive process. The substantial funds freed up by ending enforcement and mass incarceration could be redirected to address this critical need.

However, it is not a certainty that drug legalization would trigger the massive spike in addiction predicted by Kleiman. In fact, evidence suggests otherwise. The Netherlands effectively decriminalized marijuana use and possession in 1976, followed by Australia, the Czech Republic, Italy, Germany, and New York State. In none of these jurisdictions did marijuana become a significant public health or public order problem. While marijuana’s non-physical addictiveness makes it a less concerning case study, Portugal provides a more relevant example. In 2001, Portugal took the radical step of decriminalizing not only marijuana but also cocaine, heroin, and all other drugs. Decriminalization in Portugal means that while drug sales remain a serious crime, the purchase, use, and possession of up to a ten-day supply are treated as administrative offenses, not criminal acts. No other nation has adopted such a comprehensive decriminalization approach, and the results have been remarkable. The anticipated influx of “drug tourists” never materialized. Teenage drug use initially increased slightly but then stabilized, possibly as the novelty effect waned. (Teenage drug use patterns, particularly among eighth graders, are often considered leading indicators of future societal drug use trends.)

While the lifetime prevalence of adult drug use in Portugal rose marginally, problematic drug use – habitual use of hard drugs – actually declined after decriminalization, from 7.6 to 6.8 per 1,000 people. This contrasts sharply with neighboring Italy, which did not decriminalize, where rates rose from 6.0 to 8.6 per 1,000 people during the same period. Decriminalization in Portugal also facilitated harm reduction strategies. The legal availability of sterile syringes for addicts significantly reduced HIV infection rates, from 907 cases in 2000 to 267 in 2008. Cases of full-blown AIDS among addicts also fell dramatically, from 506 to 108 during the same timeframe.

Portugal’s decriminalization policy has also had a striking impact on its prison population. The number of inmates incarcerated for drug offenses decreased by more than half, and drug offenders now constitute only 21 percent of the total prison population. A comparable reduction in the United States would free approximately 260,000 individuals – equivalent to releasing the entire population of Buffalo, New York, from incarceration.

When considering applying Portugal’s experience to the United States, it is crucial to recognize that Portugal’s decriminalization was not simply a reckless opening of access to dangerous drugs. Portugal simultaneously invested heavily in drug treatment, expanding treatment capacity by over 50 percent. They established Commissions for the Dissuasion of Drug Addiction, composed of a doctor, a social worker, and an attorney, empowered to refer drug users to treatment and, in some cases, impose minor fines. Portugal’s decriminalization experiment occurred within a broader context of expanding social services since the 1970s, including the implementation of a guaranteed minimum income in the late 1990s. While the expansion of the welfare state may have contributed to Portugal’s well-documented economic challenges, it likely also played a role in the observed decline in problem drug use.

Decriminalization has been widely considered a success in Portugal. There is no serious political movement to reverse the policy, and association with the decriminalization law is considered politically advantageous. Former Prime Minister José Sócrates, during his successful 2009 reelection campaign, proudly highlighted his role in establishing the policy.

Models for Legalization: State Monopoly vs. Regulated Market

Despite the apparent success of Portugal’s decriminalization approach, simply decriminalizing drugs in the United States may not be sufficient. Decriminalization does not grant the government control over drug purity or dosage, nor does it generate tax revenue from drug sales. Organized crime continues to control the supply and distribution networks, and drug-related violence, corruption, and aggressive law enforcement persist. Consequently, the impact of drug decriminalization on crime rates in Portugal remains unclear. Some crimes closely associated with drug use, such as street robberies and auto theft, increased after decriminalization, while others, like thefts from homes and businesses, decreased. A Portuguese police study indicated a rise in opportunistic crimes and a decline in premeditated and violent crimes, but it could not definitively attribute these changes to drug decriminalization. Furthermore, heavy-handed enforcement, even in a decriminalized context, often prioritizes scare tactics over honest inquiry, experimentation, and data collection, which is counterproductive when dealing with substances as dangerous as heroin, cocaine, and methamphetamine.

Portuguese-style decriminalization may also be impractical in the United States due to the significant differences in governance structures. Portugal is a relatively small, centralized nation with national laws and a unified national police force. The United States, in contrast, is a complex patchwork of jurisdictions, with thousands of overlapping law enforcement agencies and prosecutors at the local, county, state, and federal levels. The conflict between Philadelphia’s city council decriminalizing marijuana possession and state police continuing to make arrests for the same offense illustrates this jurisdictional complexity. Even with marijuana legal in several states and D.C., federal law still classifies it as illegal as heroin or LSD, and more tightly controlled than cocaine or pharmaceutical opioids. While the Obama Administration adopted a policy of non-interference with state-level marijuana legalization, federal policy remains unchanged and future administrations may adopt different approaches. To fully realize the benefits of managing drugs as a matter of public health and safety, rather than primarily as a law enforcement issue, drug legalization must occur at every level of American jurisprudence, mirroring the repeal of alcohol Prohibition in 1933.

One of the contributing factors to alcohol Prohibition was the “tied house” system, where saloons owned by alcohol producers aggressively promoted their products. As Prohibition was nearing its end, John D. Rockefeller commissioned a report, Toward Liquor Control, advocating for complete government control of alcohol distribution. Rockefeller argued, “Only as the profit motive is eliminated is there any hope of controlling the liquor traffic in the interests of a decent society.” However, this recommendation was never fully implemented. While tied houses were outlawed, private companies like Seagram and Anheuser-Busch grew into industry giants in alcohol manufacturing and sales. Only eighteen states adopted any degree of direct government control over alcohol distribution.

Americans have become accustomed to living with the consequences of legal alcohol, despite its undeniable societal costs in terms of lives lost and economic burden. Yet, few advocate for a return to Prohibition, in part because the alcohol industry is immensely lucrative and politically powerful. Binge drinkers, comprising 20 percent of the drinking population, consume over half of all alcohol sold, revealing the industry’s reliance on excessive consumption despite public pronouncements about “responsible drinking.” The alcohol industry’s political influence also keeps taxation rates low. Kleiman estimates that alcohol taxes amount to approximately a dime per drink, while the societal cost in disease, accidents, and violence is roughly fifteen times higher. Neither the binge-drinking-dependent economics of the alcohol industry nor its regulatory capture are desirable models to emulate when considering legalizing substances like heroin and crack cocaine. To minimize addiction, protect children, ensure drug purity and consistent dosage, and limit drugged driving, a more effective legalization framework than the one adopted for alcohol is necessary. The rejection of marijuana legalization by Ohio voters in November, largely due to the proposed initiative granting exclusive cultivation and distribution rights to ten companies that sponsored the initiative, highlights public concern about potential industry capture and inequitable market structures.

The present moment offers a unique opportunity to establish a state monopoly on drug distribution, as Rockefeller advocated for alcohol in 1933, before private industry interests become too entrenched. Switzerland, Germany, and the Netherlands have successfully implemented programs providing legal heroin to addicts through government-run dispensaries, removing the profit motive from distribution. A state monopoly offers significant advantages over even a tightly regulated for-profit market.

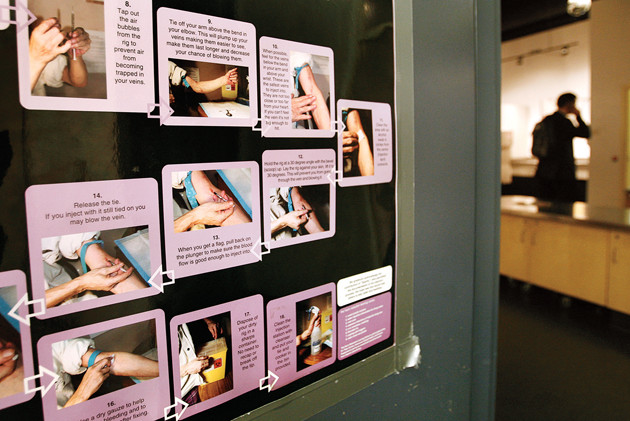

A poster showing how to use a syringe at Insite, a safe-injection site for drug addicts in Vancouver, British Columbia © Andy Clark/Reuters

A poster showing how to use a syringe at Insite, a safe-injection site for drug addicts in Vancouver, British Columbia © Andy Clark/Reuters

While some of the eighteen U.S. states that initially adopted government control over alcohol distribution after Prohibition later weakened these systems by privatizing wholesale and/or retail operations, research indicates the benefits of state control. A 2013 University of Michigan study found that even in “weak monopoly” states, spirits consumption was 12 to 15 percent lower than in states with private liquor stores or grocery stores. States retaining retail control also experienced approximately 7 to 9 percent lower rates of alcohol-related traffic fatalities and lower crime rates.

A general consensus among those seriously considering the end of drug prohibition is the need to discourage consumption. A regulated, for-profit market can incorporate disincentives through measures like advertising and promotion restrictions (or outright bans), preventing marketing to children, establishing minimum distances between retail outlets and schools, setting stringent rules on dosage and purity, and limiting the number of stores and their operating hours. However, in a for-profit system, taxation is the primary mechanism for government price control, which is a crucial factor in influencing consumption. Setting appropriate tax levels and adjusting them effectively is a complex challenge. Current federal alcohol taxes are based on potency, but applying this to cannabis, with its varying THC content across strains, would be impractical. Taxing by weight might incentivize the consumption of more potent drugs. Taxing by price requires constant monitoring of post-legalization price fluctuations, which are likely to plummet as the “prohibition premium” disappears and competition intensifies. Legislators would need to regularly raise taxes, a politically unpopular move, to maintain prices at a level that discourages excessive use without fueling a black market for untaxed drugs.

Pat Oglesby, a tax lawyer and former chief tax counsel for the Senate Finance Committee, highlights the difficulty of adjusting taxes quickly enough: “Legislatures love lowering taxes. Getting them to raise taxes is like pulling teeth.” Excessively high taxes, however, risk reviving the illicit drug market.

A government monopoly on distribution circumvents this problem by making price adjustments an administrative, rather than legislative, matter. Government officials could flexibly adjust prices – even daily if necessary – to minimize use without creating a black market incentive. Private companies could still handle drug production, supplying government stores similar to how alcohol producers supply state liquor stores. If production costs decrease due to innovation or competition, the government agency would directly benefit from increased revenues. Government control also simplifies the regulation of dosage and purity and allows for direct control over advertising, packaging, and promotions.

Furthermore, a state monopoly ensures that profits accrue to the public, not private shareholders. States with government-controlled alcohol distribution collect significantly more revenue than states relying on private sales and taxation, with revenue differences ranging from 82 to 90 percent depending on the level of state control. While profiting from a product the government aims to discourage might seem morally ambiguous, this is the established model for tobacco, alcohol, and gambling. Governments often mitigate this moral concern by earmarking revenues for public benefit, such as education or, in the case of drugs, addiction treatment programs. Adopting a state monopoly model initially offers the advantage of easier transition to a regulated free market if the state monopoly proves ineffective, whereas moving in the opposite direction would be more politically challenging.

The Challenges of Transition and Regulation

Despite the potential advantages of a state monopoly, the current federal prohibition of marijuana, cocaine, and heroin, and stringent restrictions on methamphetamine, make state-level drug monopolies modeled after state liquor stores unlikely in the near term. Even if international bans on Schedule I drugs were lifted, garnering sufficient political will in the U.S. Congress to legalize these substances, let alone expand government control to distribute them, remains a significant hurdle. While executive branch tolerance of state-level marijuana legalization experiments is one thing, fundamentally shifting deeply entrenched conservative congressional views is a much more complex and arduous process.

This federal legal landscape necessitates exploring “second best” options: state-level experiments that navigate around the federal marijuana ban and license private industries. Colorado’s experience with marijuana legalization offers valuable insights into this approach.

Colorado has permitted medical marijuana since 2000 through a system of licensed private dispensaries. Initially, Colorado mandated vertical integration, requiring dispensaries to sell only products they cultivated themselves, mirroring the pre-Prohibition “tied house” system. The rationale was simplified regulation from “seed to sale.” In November 2012, 55 percent of Colorado voters approved Amendment 64, legalizing recreational marijuana. Strategic timing, placing marijuana legalization on the ballot, helped boost voter turnout among young and progressive demographics, contributing to President Obama’s victory in the state. Following legalization, Colorado opted for a system of licensed private businesses rather than a state monopoly. In 2014, the vertical integration requirement for recreational dispensaries was removed, allowing businesses to specialize in cultivation or retail. Five weeks after the vote, Governor John Hickenlooper formalized the results, and adults aged 21 and over could legally possess and use marijuana. However, retail stores and commercial cultivators were not permitted to open until January 2014, fourteen months after the vote. This delay was intended to provide time for the state to expand the Marijuana Enforcement Division within the Department of Revenue to regulate retail marijuana and to develop rules regarding signage, advertising, waste disposal, video surveillance, labeling, taxes, and proximity to schools.

A man prepares a heroin injection at Insite © Ed Ou/Getty Images Reportage

A man prepares a heroin injection at Insite © Ed Ou/Getty Images Reportage

Colorado’s legal marijuana market is already exhibiting economic patterns similar to the alcohol industry. Daily marijuana smokers, constituting only 23 percent of the state’s marijuana-using population, consume 67 percent of all marijuana sold. This pattern may have existed even under prohibition, but the illegal nature of the market made tracking such data impossible. The legal, for-profit marijuana industry in Colorado, like the alcohol industry, is heavily reliant on heavy users. From a public health perspective, this dependence is concerning.

The impact of legalization on crime in Colorado has been complex and difficult to definitively assess. Overall crime in Denver decreased by nearly 2 percent in 2014, the first full year of marijuana legalization. Surprisingly, surveys of 40,000 teenagers conducted before and after legalization indicated that while fewer teenagers perceived marijuana as harmful – as opponents of legalization predicted – fewer were smoking pot. Possible explanations include inaccurate self-reporting, statistical anomalies, reduced availability of illegal dealers due to competition from legal stores, or a potential decline in marijuana’s perceived “cachet” once legalized.

Colorado’s legalization rollout has encountered challenges. The fourteen-month period between the vote and store openings proved insufficient to develop comprehensive regulations for issues like pesticide use in cultivation and dosage control in edibles. Developing new training curricula for law enforcement, who faced uncertainty about handling marijuana-related situations, also lagged behind. Home grow operations have led to issues like electrical fires and mold infestations. Marijuana greenhouses and stores have become targets for burglaries and robberies. Local jurisdictions were granted the authority to decide whether to allow retail marijuana stores, and initial participation was limited, with only thirty-five counties opting in. This limited initial rollout partially explains lower-than-anticipated tax revenues in the first six months of legal sales. The 10 percent retail marijuana tax, in addition to standard sales tax, may also be too high, potentially incentivizing continued black market purchases. The widespread availability of medical marijuana cards (held by over 2 percent of Colorado’s population) further complicates the recreational market, as medical marijuana is subject only to standard sales tax. However, marijuana tax revenues in Colorado have increased significantly over time, reaching approximately $135 million in 2015, nearly double the previous year’s revenue.

A bud tender holds a jar of marijuana buds under a magnifying glass at a dispensary in Denver © Benjamin Rasmussen/Offset

A bud tender holds a jar of marijuana buds under a magnifying glass at a dispensary in Denver © Benjamin Rasmussen/Offset

Addressing unlicensed grow operations and training law enforcement have been relatively manageable. A more significant long-term challenge is preventing large corporations from dominating the legal marijuana industry and manipulating the market to their advantage. Even with recreational marijuana legal in only four states and D.C., and medical marijuana legal in twenty-three states, the legitimate cannabis industry is already valued at $5.4 billion. Forbes magazine has published lists of “Hottest Publicly Traded Marijuana Companies.” Cannabis stocks encompass biotech firms, specialized vending machine manufacturers, and vaporizer producers. The combined value of marijuana stocks surged by 50 percent in 2013 and by 150 percent in the first three weeks of 2014, before settling to a still-impressive 38 percent gain for the year. MJardin, a company specializing in turnkey growing operations, announced consideration of an initial public offering in September 2014. Even the Wall Street Journal now analyzes marijuana as a serious investment opportunity. These substantial investments are being made despite recreational marijuana remaining illegal in the vast majority of U.S. states and under federal law.

The citizens of U.S. jurisdictions that legalized marijuana may have initiated a more transformative process than initially anticipated. Ira Glasser, former head of the American Civil Liberties Union, argues, “Without marijuana prohibition, the government can’t sustain the drug war. Without marijuana, the use of drugs is negligible, and you can’t justify the law-enforcement and prison spending on the other drugs. Their use is vanishingly small. I always thought that if you could cut the marijuana head off the beast, the drug war couldn’t be sustained.”

Even in Boulder, Colorado, a city known for its progressive stance on marijuana, city manager Jane Brautigam reported that “it’s not marijuana gone wild.” During a 2014 conference call, she noted that most residents were “feeling okay about it.” Marijuana-related arrests in Colorado decreased by 80 percent, with approximately 2,000 arrests in 2014 compared to nearly 10,000 in 2011. While Brautigam’s office has had to shut down a few marijuana businesses for regulatory violations, the number is comparable to other industries. The anticipated widespread public consumption of marijuana has not materialized. Boulder’s city communications director, Patrick von Keyserling, confirmed in January that things were continuing smoothly, largely due to the industry being “very well-regulated.”

In Colorado, now that the initial novelty has subsided, there is a growing sense of smug satisfaction at having taken a progressive and sensible step. Despite ongoing divisions on issues like immigration, gun control, and climate change, Colorado police no longer dedicate resources to pursuing marijuana smokers. Adults no longer need to worry about neighbors complaining about marijuana odors. Even if marijuana tax revenues have not yet met initial projections, the state is generating revenue from a product that previously incurred significant costs. Marijuana has become “no big deal.” Coloradans now view states that continue to treat marijuana as a major public threat with a sense of bewilderment.

While marijuana legalization is gaining traction, no one interviewed for this article envisions a future where heroin, cocaine, or methamphetamine are sold as freely as marijuana in Colorado or vodka in state liquor stores. Most researchers envision a supervised distribution model for harder drugs. This model might involve a network of counselors, not necessarily physicians, who would monitor an individual’s drug use and its integration into their life. Kleiman envisions a system where cocaine users could set their own dosage quotas and navigate a bureaucratic process to increase their quota or access counseling if needed. This system aims to empower individuals to make informed decisions and provide a “long-term self a fighting chance against your short-term self.”

Eric Sterling of the Criminal Justice Policy Foundation proposes a similar model. Individuals seeking cocaine for creative enhancement or sexual pleasure might engage in a counseling process to explore underlying issues and alternative solutions. For psychedelic drugs like LSD, Sterling suggests licensed “trip leaders,” analogous to wilderness guides, trained and insured to guide individuals through potentially challenging psychedelic experiences.

While regulated systems are envisioned, the possibility of individuals bypassing regulated channels and continuing to purchase drugs on the black market remains. However, Sterling points out the inherent risks of the black market, citing the tragic overdose death of Philip Seymour Hoffman as an example that “nobody is safe.” He also emphasizes the “hassle to be an addict” in the illicit market, involving finding dealers, scoring drugs, and finding safe places to use them. If a legal, regulated system is well-designed – ensuring affordable, trustworthy drugs, streamlined access, and reasonable taxation – users are likely to prefer it to the black market. Competition, not violence, would then become the primary mechanism for dismantling criminal drug distribution networks. Sterling concludes that the ultimate goal is “building the proper cultural context for using drugs,” a context where “the exaggerations and the falsehoods get extinguished.”

In 2009, Britain’s Transform Drug Policy Foundation published a comprehensive report, “After the War on Drugs: Blueprint for Regulation,” suggesting a licensing system for buying and using drugs, with sanctions for violations, similar to gun licenses or driver’s licenses. User purchases would be tracked electronically to monitor usage patterns and enable early intervention. Legal vendors would bear partial responsibility for “socially destructive incidents,” akin to bartender liability for serving intoxicated patrons. The report advocates for pricing drugs high enough to “discourage misuse, and sufficiently low to ensure that under-cutting… is not profitable for illicit drug suppliers.” While favoring a more laissez-faire market approach than European and Canadian government-run heroin distribution systems, the report strongly recommends a complete ban on advertising and marketing, and advocates for plain, pharmaceutical-style packaging.

Reflecting on my own experience with marijuana legalization, I voted in favor of it as a sensible political and economic measure. One evening, considering the local “Cruiser Ride” bicycle parade, I decided to try marijuana again after years of abstinence. The experience was illuminating. Previously, obtaining marijuana would have been a clandestine and uncertain endeavor. Now, I simply cycled to a nearby retail store, the Green Room. Despite my age, I was carded in a reception area adorned with portraits of Jerry Garcia and Jimi Hendrix. A bud tender escorted me to a counter, where I purchased a pre-rolled joint for $10. The packaging included educational materials on edibles, emphasizing responsible consumption and dosage. The selection of marijuana strains was extensive and sophisticated. The pre-rolled joint, packaged in a green plastic tube with a “department of revenue, marijuana” sticker, was professionally made and potent. For someone who started buying marijuana in back alleys, this legal and regulated experience felt like a different world.

Consumption was restricted to private residences. Following instructions, I started with a single inhalation. Within twenty minutes, I experienced a pleasant and familiar “stoned” sensation, without the sluggishness or paranoia associated with past experiences. The single joint proved to be surprisingly potent and long-lasting.

Legalization has reintroduced me to marijuana consumption, but it has not negatively impacted my life. I consume responsibly, and it has not interfered with my professional or personal responsibilities.

As we contemplate drug legalization, it is crucial to acknowledge that detailed plans are unlikely to perfectly anticipate the complexities of real-world implementation. Eric Sterling cautions, “People are thinking about the utopian endgame, but the transition will be unpredictable. Whatever system of regulation gets set up, there will be people who exploit the edges. But that’s true for speeding, for alcohol, for guns.” Without a state-run monopoly, diverse legal and regulated drug markets are likely to emerge, and these markets will not solve every problem. However, the imperfections of a regulated system are likely to be less damaging than the ongoing devastation caused by prohibition. Legalizing and regulating drug markets will likely be a messy process, particularly in the short term. However, in a technocratic, capitalist, and fundamentally free society like the United States, education, counseling, treatment, distribution, regulation, pricing, and taxation represent a more effective and humane approach than the violent and corrupt suppression of immense black markets.