Navigating through Colonial Williamsburg, the historical echoes faded as I approached a less conventional landmark. My Uber passed by quaint, old-world charm and then turned onto a modern strip, guided by a tweet from an unlikely source: John Hinckley, Jr., the man whose name is forever linked to the 1981 assassination attempt on President Ronald Reagan. The destination was not a relic of the past, but a potential future – the location of Hinckley’s announced record store. This wasn’t the historical district, but a mundane commercial zone, lined with auto shops and familiar fast-food chains, leading to a modest, whitewashed building. Could this be the place where John Hinckley, now decades removed from his infamous act, was attempting a new grand opening?

The scene was starkly ordinary. A strip mall, unremarkable and somewhat downcast, housed a tax service, a Domino’s, and a small Spanish church. A pizza delivery driver, in a car adorned with a Jesus bumper sticker, hurried out. The only activity seemed to be the line at the Hardee’s drive-thru. It felt incongruous, almost jarring. Was this truly where the man who altered presidential history might set up shop? Sandwiched between a vacant party supply store and the silent Jazzercise studio, it seemed a surreal comedown for a figure once so intensely scrutinized. History, in its strange way, had led “Hinkley John” to this very spot.

Strip Mall Location of Hinckley's Record Store

Strip Mall Location of Hinckley's Record Store

Photograph by Sylvie McNamara.

Fear wasn’t my primary emotion as I considered meeting John Hinckley. The once “fearsome lone gunman” of the 20th century had been living a different reality. In 2016, after over thirty years of court-ordered psychiatric care, a federal judge deemed Hinckley rehabilitated and released him to his mother’s care. By 2022, all remaining restrictions were lifted, granting “hinkley john” complete freedom for the first time in over four decades. With this newfound liberty, Hinckley chose an unexpected path: a life in the arts.

Today, John Hinckley’s presence is mostly digital. He shares his songs on YouTube, sells paintings of his cat on eBay, and engages on social media. His online pronouncements are often peaceful, even platitudinous, such as a tweet advocating for peace after a shooting incident involving Donald Trump. He briefly resurfaced in news headlines for his planned “Redemption Tour” in 2022, a series of concerts across the country that were ultimately canceled due to public outcry. Hinckley, labeling himself a “victim of cancel culture,” sparked further online debate.

The discomfort surrounding the Redemption Tour seemed rooted in the perception of attention-seeking. Without his notoriety, a 67-year-old in Virginia strumming a guitar might be overlooked. However, Hinckley’s past act of violence, shooting President Reagan, gave him a macabre platform. His motive in 1981 wasn’t political; it was a desperate bid for fame, hoping to impress actress Jodie Foster. The Redemption Tour echoed this unsettling desire for recognition, raising concerns about the continuity of his impulses. The last time Hinckley sought fame, it ended in tragedy.

The concept of a record store, however, felt different. It suggested a degree of humility. “Hinkley John” as a small business owner, a local proprietor miles from the historical grandeur of Colonial Williamsburg, seemed a less grandiose, even mundane, pursuit. A physical space offered him control, a venue where he could share his music without the fear of cancellations. Ideally, it could become a haven, a place to connect with music lovers and build a life around his passion, a dream he held even before the events of 1981.

Perhaps that’s what drew me to Williamsburg. This version of Hinckley’s redemption seemed more grounded, more genuine. His record store, an unconventional passion project, felt like a modest attempt at a third act, a chance rarely afforded to someone with his history. Yet, it also felt precarious. Small businesses face daunting odds.

The address Hinckley tweeted lacked a specific suite number, so I started my search at one end of the strip mall. I peered into a darkened boxing gym, the expansive Jazzercise studio, and a small church adorned with artificial flowers. Then, a large red “for-rent” sign caught my eye, hanging on a dusty storefront window. This seemed likely – the future record store. I knocked, but no one answered.

Next door, at an unmarked business with a pristine stainless-steel kitchen, a man opened the door. Identifying myself as a reporter, I was immediately met with, “Oh, are you here about Hinckley?”

This was Chris Waller, a food truck owner preparing to launch a smashburger restaurant. “Never met him, never seen him,” Waller said about his potential neighbor, “hinkley john.” However, he knew about the record store from a news article his father had forwarded, an article he assumed many others had also seen. “Traffic has increased crazily lately,” he noted. “I’ve seen a lot more cars through here in the last few days.”

“How do you feel about him moving in?” I inquired.

“Rather not say,” was his guarded reply.

“Would you buy records from him?”

“No, but I also don’t have a record player. I think most music stores are going out of business with streaming and everything.”

Waller offered a helpful tip: the “space available” sign had recently been removed from the old party store a few doors down. He suspected that was Hinckley’s chosen location. To confirm, he suggested contacting the landlords, Extra Space Storage, located at the end of the strip mall, who apparently managed the entire property.

A YouTube search for “John Hinckley” reveals a diverse range of content: news reports, documentaries, and Hinckley’s own videos. One video, titled “John Hinckley Speaks About Peace and Harmony,” recorded after the attempted assassination of former President Trump, stands out. “I know I’m known for an act of violence,” Hinckley states, “but I live a peaceful life now.” His tone is flat, his expression neutral as he urges viewers to “try and reject violence in all its forms.” The video is simple, almost amateurish, the camera angled upwards, the reflection of a computer screen glinting off his dark sunglasses. The top comment aptly captures the strangeness of it all: “This is the strangest fucking timeline the world could’ve possibly ever gotten.”

Primarily, Hinckley’s YouTube channel is dedicated to his music. There he is, somewhat heavy-set and pale, with thinning white hair, singing melancholic songs into his computer, accompanying himself on a caramel-colored acoustic guitar emblazoned with his name in white block letters. His music is reminiscent of classic Americana, the kind you might hear in a coffee shop – earnest, traditional, and generally in tune.

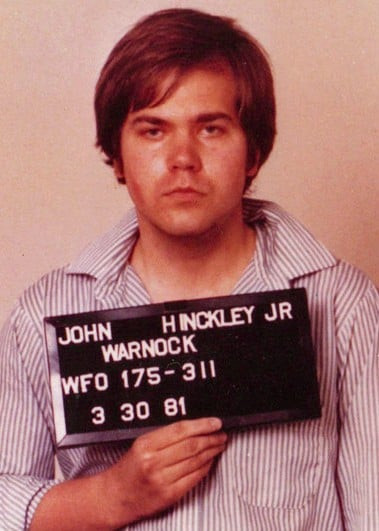

Hinckley’s lyrics are straightforward, often introspective and searching, revealing a yearning for redemption. Lines like, “I got through the darkest night / Now I hope to make things right,” or “You never thought I’d be free / You don’t know a different side of me,” resonate with his life story. Occasionally, in videos where he removes his sunglasses, glimpses of the young man from his infamous mugshot emerge – the light eyes, arched eyebrows, and snub nose of a 25-year-old. In one video, the ghost of that younger “hinkley john” sings, “Tomorrow is another day / The best is yet to come / I have found a different way / It’s baffling to some.”

John Hinckley Jr. Mugshot

John Hinckley Jr. Mugshot

Photograph courtesy of the FBI.

“Redemption” is a central theme in the John Hinckley narrative. It’s the title of his ill-fated tour and his debut album. His website mentions the “National Redemption Party” as the “political wing” of his fan community. Redemption carries multiple meanings: religious cleansing of sin, reclaiming something owed. For Hinckley, it seems to be about atonement. “My definition of redemption is to make amends for all the negativity that I created in 1981,” he told the New York Times Magazine. “I’m trying to redeem myself through positive music, through a thing that people really like—as opposed to the things they really hated about me in 1981.”

Hinckley’s actions since his release have tested public perceptions of justice and forgiveness. He targeted a president, along with a police officer, a Secret Service agent, and a presidential aide, yet he walks free. Is this the legal system working as intended – rehabilitation and reintegration? Or is it a failure? Reagan’s daughter, Patti Davis, has voiced the enduring pain of the victims’ families, describing the shooting as “a shredded nerve that will never heal.” Even for those who support Hinckley’s release, his pursuit of a music career raises questions. Is it acceptable for him to seek fame after such infamy? Is it fair to grant him freedom but deny him the opportunity to use it to pursue his ambitions?

In 2022, when Hinckley announced his Redemption Tour, I explored local reactions, asking DC music venue owners if they would book him. Bill Spieler of DC9 was firmly against it, recalling the fear in DC in 1981. Sandra Basanti of Pie Shop was more open, emphasizing the importance of not “demonizing people who have a history” if they have served their time. Dante Ferrando of the Black Cat focused on the music itself, finding it “like something that would be a legitimate submission,” based on a brief listen.

These varied responses reflect the complex moral puzzle Hinckley presents. He remains an enigma, a persistent reminder of unresolved questions. Is his music a genuine attempt to honor his freedom, or an exploitation of it? Does he owe society obscurity, or is he entitled to a chance at amends? Perhaps the question has shifted. Having served his time, does “hinkley john” deserve to be seen as simply himself, on his own terms?

On my way to Extra Space Storage, I stopped at Domino’s, curious about local employee perspectives. A woman preparing pizza dough hadn’t heard about the record store, but seemed more skeptical of the business idea than of John Hinckley himself.

“People still buy records?” she wondered. “Good for them.”

“I really don’t care if he has a past,” she continued. “If we don’t let them work, how are they truly going to be rehabilitated?” However, she doubted his business acumen, noting the lack of activity at the storefront and questioning the timing of opening after Christmas.

“Wait,” she paused, “so he assassinated JFK?” Misinformation, it seemed, still clouded the Hinckley narrative.

Around the corner, the Extra Space Storage office was bright and airy. The employee at the desk, initially providing his full name but later requesting anonymity, cited his wife’s discomfort with his conversation about John Hinckley. He likened Hinckley opening a record store to “the Green River Killer setting up a daycare” and stated he wouldn’t be a customer.

He didn’t know about rental agreements for the storefronts but provided the contact information for the commercial leasing manager who could confirm if Hinckley had leased the party store space. Before calling, I decided to check the storefront again, hoping to find Hinckley setting up shop.

Parties Galore Storefront

Parties Galore Storefront

Photograph by Sylvie McNamara.

Next to Domino’s, the “Parties Galore, Cakes & More” sign still hung brightly. Peering inside, I saw a small, sage-green front room with blue and pink stripes painted around the walls. Saloon doors hinted at a back room, and glimpses of cabinetry were visible through a wall cutout. Outside, a faded American flag drooped from a pole, about twenty feet from the entrance.

Despite Hinckley’s deleted tweet suggesting an imminent grand opening, the storefront was empty. No records, no decorations, not even basic furniture. Standing in the cold, a sense of unease crept in. Had I been too naive? Was the record store a fantasy, never intended to materialize?

Parties Galore Storefront Detail

Parties Galore Storefront Detail

Photograph by Sylvie McNamara.

For years, court restrictions had prevented Hinckley from speaking to the press, partly to manage his grandiosity and for his own protection. The fear was that unwanted attention could derail his delicate reintegration. While those restrictions were lifted, the ethics of pursuing this story felt complex. Was it justifiable to scrutinize the business plans of a man with mental illness, who had spent decades removed from normal life? I wrestled with this ethical dilemma on the train to Williamsburg. I went anyway, telling myself I was exploring the possibility of a new chapter for him, while acknowledging the undeniable pull of the story itself – extracting content from a man whose past perpetually overshadowed his present.

Since Hinckley wasn’t at the store, I emailed him, not expecting a reply. That evening, on the Amtrak back to DC, an email arrived from him. The record store was “on hold.” His plan was to sell his collection of about 1,000 rock albums and some guitars, but the negative reaction to the announcement had made him “uncomfortable opening a store when there was such a negative reaction.” The landlord didn’t respond to my calls, but a company spokesperson later confirmed: “John Hinckley expressed an interest in renting the property, but that’s where his interaction with us ended. There was no lease agreement finalized.”

Reflecting on the apparent end of Hinckley’s record store dream, I recalled a conversation at a nearby Family Dollar. Shemica Parker, the store manager, wearing a “Merry Christmas” shirt and gold necklaces, had a different perspective. When asked about “hinkley john” moving in, she said, “To be honest, I’m a people’s person, I love everybody.” Would she buy his records? “If his music is good, I would,” she said, and played his YouTube music on her phone.

Hinckley’s song “Lonely Dreamer” filled the store, amidst shelves of everyday goods. As he sang of dreams and overcoming hardship, Parker nodded, smiling. “I like this type of music,” she said. “A couple of months ago, I was going through something—a terrible, terrible situation. I was alone and daydreaming and sitting there just thinking and thinking and thinking. And once you listen to music like this, it relaxes you.”

Parker acknowledged Hinckley’s past, his crime, and his journey through mental health treatment and release. “People go through things,” Parker said. “Some things happen when you go through life. He did the crime, and he did the time, so now just give the man a second chance.”

Perhaps that second chance is still possible. Hinckley’s final emails were subdued but not defeated. He still hopes to open a record store someday, in a “safe” location. For now, he wrote, “I’ll just keep selling records online.”

More: John Hinckley Jr.Record Stores

Join the conversation!

Share Tweet

Sylvie McNamara

Staff Writer