John Milius is a name synonymous with a certain brand of Hollywood filmmaking: bold, audacious, and unapologetically masculine. Stepping into his office at Warner Bros., as described, immediately paints a picture of the man – a blend of surfer cool and military fervor, surrounded by artifacts that speak to his diverse passions and inspirations. More than just a director known for iconic films, John Milius is a writer, a craftsman of stories that have resonated deeply within cinematic culture. This article delves into the world of Director John Milius, exploring his journey from a surfer with military aspirations to a celebrated, albeit controversial, figure in Hollywood.

John Milius on the set of Conan the Barbarian with Arnold Schwarzenegger

John Milius on the set of Conan the Barbarian with Arnold Schwarzenegger

From Surfboards to Screenplays: The Early Life of John Milius

Born in St. Louis, John Milius’s formative years shifted dramatically when his family relocated to Southern California at the age of seven. It was here he discovered surfing, an experience he described as transformative, akin to a “religion.” This intense passion, shared with his surfer friends who nicknamed him “Yeti,” offered a sense of purpose and exhilaration that he found unparalleled. Milius initially aimed for a career in the military, harboring ambitions to become an Army officer. However, an asthmatic condition prevented him from enlisting. This setback led him down an unexpected path – film school. At the University of Southern California (USC), Milius didn’t foresee a future beyond his love for surfing, but fate, and his inherent storytelling talent, had other plans.

The USC Film School Mafia and the Rise of a Screenwriting Star

Emerging from USC’s prestigious film school, Milius became part of the famed “USC Film School Mafia,” a group of filmmakers who would go on to redefine Hollywood. He quickly established himself as a prolific and sought-after screenwriter. His early screenplay credits are a testament to his raw talent and distinctive voice. Milius penned scripts for critically acclaimed films like Jeremiah Johnson and Judge Roy Bean, and contributed, uncredited, to the iconic Dirty Harry. He further solidified his reputation with Magnum Force and the legendary Apocalypse Now. These screenwriting achievements provided him with the leverage to step into the director’s chair, bringing his own scripts to life.

As a director, John Milius translated his unique vision onto the screen. He directed Dillinger, The Wind and the Lion, Big Wednesday, the epic Conan the Barbarian (which he co-wrote with Oliver Stone), the Cold War thriller Red Dawn, Farewell to the King, Flight of the Intruder, and Rough Riders. His screenplay for Apocalypse Now, co-credited to Francis Ford Coppola, earned him an Academy Award nomination, cementing his status as a top-tier Hollywood writer. Remarkably, Milius was hailed as “the hottest screenwriter in Hollywood” on four separate occasions, a testament to his consistent demand and creative output.

The sale of his screenplay The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean for a staggering $300,000 in 1971 (especially considering his initial asking price of $85,000) underscored his growing influence. Milius, in an Esquire interview, revealed his nonchalant attitude towards the sale, stating he wrote it primarily for his own enjoyment, highlighting his artistic integrity over pure commercial motivation. However, beyond the financial success, it was the distinct writer’s voice within his scripts that began to captivate critics and audiences alike.

The “Gifted Barbarian” and a Unique Cinematic Voice

Andrew Sarris famously dubbed Milius “the gifted barbarian,” a moniker that captured the raw, untamed energy of his writing and filmmaking. Pauline Kael, a prominent film critic, recognized Milius’s singular voice early in his career, even across films directed by others like Sydney Pollack (Jeremiah Johnson) and John Huston (Judge Roy Bean). Kael pointed to Milius’s fascination with violence and what she perceived as a glorification of lawlessness, sparking early debates around his work’s themes. The recognition of Milius as a distinct writer challenged the prevailing auteur theory, emphasizing the crucial role of the screenwriter and placing a spotlight on the gun-toting, outspoken writer emerging from Hollywood in the 1970s.

Paul Newman as Judge Roy Bean in The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean

Paul Newman as Judge Roy Bean in The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean

John Milius, the director, and writer, possesses a clear and unwavering worldview that permeates his films. His characters are often defined by a strong moral code, standing firm against societal pressures. Martial combat and purposeful violence are recurring themes, elevating his characters to almost mythical proportions. Milius himself aptly summarized his somewhat anachronistic perspective, “The world I admire was dead before I was born,” revealing a fascination with bygone eras and traditional values. His outspoken nature and rejection of what he saw as “the hypocrisy of the Writers Guild” further cemented his image as a Hollywood outsider, a “God’s lonely man” within the industry, reminding us of the personal cost writers often bear for integrity.

Film School Foundations: Learning the Craft

When asked about his film school experience, Milius emphasized the foundational importance of learning screenplay form. He credited his teacher, Irwin Blacker, who, despite his rigid focus on format, encouraged radical storytelling and experimentation within that structure. Blacker’s philosophy was to master the technicalities of screenwriting, providing a framework for students to then unleash their creativity. Milius highlighted Blacker’s approach: “I can’t teach you how to write the content, but I can certainly demand that you do it in the proper form.” This rigorous training in form, surprisingly, liberated Milius to explore unconventional narrative structures, flashbacks, flash-forwards, and narration – all tools at a screenwriter’s disposal.

Milius uses Moby Dick as a prime example of excellent screenwriting structure, emphasizing character entrances and thematic threading. He also cites Kerouac’s On the Road as an influence, appreciating its sprawling, character-driven narrative, showcasing his appreciation for diverse storytelling styles. Both Moby Dick and On the Road, despite their contrasting styles, exemplify, for Milius, disciplined storytelling.

Apocalypse Now

Apocalypse Now

Apocalypse Now: From Kerouac to the River’s Edge

Milius acknowledges the Kerouac-esque, character-driven flow in his original Apocalypse Now screenplay, drawing parallels to Moby Dick as well. The narrative begins with a disillusioned character thrust into a mission – a “hunt for a white whale at the end of the river.” He emphasizes the thematic core: “somewhere there’s going to be Judgment Day, somewhere, you know, you’re gonna meet Moby Dick,” highlighting the film’s journey towards confrontation and reckoning.

Although Milius started Apocalypse Now in film school, he significantly rewrote his early drafts upon entering the industry. While these early scripts were never produced, they were optioned, providing him with early financial and professional validation.

Early Career and Creative Integrity

Milius’s entry into Hollywood was marked by early success. His initial job working for AIP’s Larry Gordon was a revelation – getting paid for writing felt like a dream. He then worked for Al Ruddy at Paramount, writing The Texans, a script he deemed “not very good.” He recognized that scripts where he compromised his vision, influenced by studio input to be more “current” or commercially viable, consistently fell short. This realization solidified his commitment to creative integrity.

Reflecting on Big Wednesday, Milius recalls resisting pressure to make it more like Animal House. He remained true to his initial vision of a coming-of-age story with “Arthurian overtones about surfers,” focusing on deeper themes rather than purely commercial trends. This commitment, he believes, is why Big Wednesday has endured and gained a dedicated following.

Warren Oates as John Dillinger in Dillinger

Warren Oates as John Dillinger in Dillinger

Myth and the Screenwriter’s Craft

Milius discusses the use of myth in screenwriting, contrasting his approach with George Lucas’s. He believes true myth isn’t consciously applied but rather organically emerges when a story resonates with universal human experiences and archetypes. He critiques Lucas’s Phantom Menace as lacking a genuine understanding of myth. Myth, for Milius, imparts a sense of importance, connecting a narrative to timeless stories. He uses classical mythology as an example, suggesting that allusions to The Iliad, for instance, can create a deeper resonance. He points to The Iliad‘s enduring power stemming from its ambiguous portrayal of war, where motivations are unclear, mirroring the complexities of real-world conflict, thus achieving mythical status.

Milius sees the Mafia and the Old West as the two great American myths, both rooted in the promise of opportunity and reinvention. He believes the enduring fascination with the Mafia stems from this mythical quality, reflecting core American narratives of ambition and the pursuit of the American Dream.

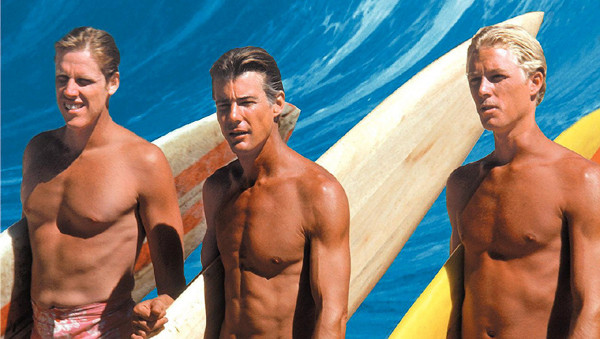

Gary Busey as Leroy Smith, Jan-Michael Vincent as Matt Johnson and William Katt as Jack Barlow in Big Wednesday

Gary Busey as Leroy Smith, Jan-Michael Vincent as Matt Johnson and William Katt as Jack Barlow in Big Wednesday

Writing Rituals and Process

Milius’s writing process is characterized by a daily discipline. He prefers writing at the end of the day, allowing ideas to incubate throughout the day as he engages in “procrastination.” Guilt, as the sun sets, becomes his motivator. He aims for at least six pages a day, written longhand, rejecting the computer’s ease of revision. He views screenwriting as “hand work,” emphasizing the unique, crafted nature of each screenplay.

Early Success and Industry Perceptions

Milius recalls his early financial success, earning a comfortable living from script options and sales. He describes a time when writers were treated with more respect, citing John Calley’s attitude at Warner Bros. during the Apocalypse Now era – valuing writers as “geniuses” and granting them creative autonomy. He contrasts this with the perceived “demeaning of the writer” in contemporary Hollywood, where writers are often treated as disposable.

He attributes the shift to the “demystification of screenwriting” through books, seminars, and tapes that attempt to formulaically break down the creative process. He scorns these “How to write a screenplay” guides, arguing that they stifle originality and create a generation of formulaic writers and executives who lack genuine creative judgment. Milius laments the focus on structure and formula over storytelling, criticizing questions like “Who are you rooting for at the end of the first act?” as symptomatic of this trend. He emphasizes simply telling a story, free from rigid adherence to imposed structures like “character arcs.”

Marlon Brando as Don Vito Corleone in the Godfather

Marlon Brando as Don Vito Corleone in the Godfather

Style and Form in Screenwriting

Milius recalls discarding conventional screenplay descriptions, focusing instead on impactful opening lines and active tense to create specific moods, as exemplified by “A gull screams, horses hooves spattered through the surf” for The Wind and the Lion and the active tense in Apocalypse Now. He notes that while such stylistic choices were once respected, they are now often met with criticism for not adhering to rigid screenplay “form.” He sees this as a decline in creative judgment within the industry.

Creative Integrity and Passion

Milius advocates for uncompromising excellence and writing for oneself, not for a perceived market. He dismisses the notion of understanding “what’s popular today,” except perhaps for Steven Spielberg. He believes true passion fuels good writing, contrasting it with “tricky” and “gimmicky” writing that may sell but lacks substance. He suggests that writers who prioritize commercial appeal over personal vision often lack a lasting body of work and a distinct voice.

Finding His Voice: Jeremiah Johnson

Milius identifies Jeremiah Johnson as the “breaking point” where he realized he had found his unique voice. His personal connection to the mountain man lifestyle and the landscape allowed him to infuse the script with authenticity and humor. He drew inspiration from Carl Sandburg’s poetry, aiming for a similar “abrupt description” and a sense of American braggadocio. He realized that this particular voice was uniquely his.

Despite initial skepticism from Sydney Pollack and Robert Redford, Milius’s authentic dialogue and understanding of the mountain man ethos proved irreplaceable. Intellectual writers brought in to rewrite the script couldn’t replicate his distinctive voice.

Nick Nolte as Learoyd in Farewell to the King

Nick Nolte as Learoyd in Farewell to the King

Career Crossroads: Following His Heart

Milius recounts a pivotal career decision: choosing to pursue his Vietnam War script (Apocalypse Now) for a smaller fee over a more lucrative rewrite assignment. Francis Ford Coppola offered him the opportunity to work on his own project, a “fork in the road” that steered him towards a more artistic, novelist-like path. He contrasts this with writers who consistently opt for higher-paying, less personally meaningful assignments, prioritizing career advancement over creative fulfillment.

He describes writing Apocalypse Now as “one of the nicest times in my life,” emphasizing the importance of following one’s heart in creative endeavors.

Creative Freedom and Collaboration with Coppola

Milius praises Coppola’s hands-off approach, fostering creative independence. Coppola encouraged artistic freedom, expecting writers to be self-sufficient and resourceful. He contrasts this with writers who constantly sought Coppola’s guidance and complained, which he viewed with less regard.

Milius’s writing process for Apocalypse Now was organic and exploratory. He had a general idea of the beginning and end but allowed the story to unfold organically, discovering the narrative path as he wrote. He compares the character Kilgore to the Cyclops from The Iliad and the Playboy bunnies to the Sirens, demonstrating his continued use of mythic and literary allusions. He aimed to immerse his characters in the “insane and most intense” aspects of the Vietnam War, rejecting conventional war movie tropes.

Danny Glover as Cmdr. Frank

Danny Glover as Cmdr. Frank

Ambition and Modern Cinema

Milius emphasizes the importance of ambition in filmmaking, lamenting its absence in much of contemporary cinema, particularly independent films focused on narrow, often trivial, themes. He criticizes the lack of ambition in modern violent films, which he sees as exploitative and devoid of consequence, contrasting them with his own films where violence has moral weight and significant repercussions.

Rewriting Dirty Harry and Leading the Public Consciousness

Milius asserts that he “brought the whole thing” to the Dirty Harry rewrite but didn’t receive full credit due to a Writers Guild technicality. He believes he should have received sole credit, mentioning Terry Malick as another writer who contributed to a later draft. He feels he led, rather than followed, public consciousness with Dirty Harry and Magnum Force, creating an “outrageous story” of a law-breaking protagonist and then exploring its moral complexities in the sequel. He conceived Dirty Harry as a “God’s lonely man,” with minimal personal life, emphasizing his isolation and dedication to his own brand of justice.

Adam Sandler as Donny in That

Adam Sandler as Donny in That

Code of Honor in Hollywood

Milius addresses the perceived ruthlessness of Hollywood, stating that “it’s okay to fuck people over and lie to them once you’ve established the ground rules.” However, he stresses the importance of a personal “code of behavior” and “code of honor” for survival and strength in the industry. This code, he argues, isn’t about external validation but about internal integrity and the ability to “finish what you start.” He emphasizes that facing the “blank page” requires inner strength and that no amount of external manipulation or shortcuts can replace genuine creative substance.

Honesty and Audience Responsibility

Milius believes a screenwriter owes the audience “a certain honesty,” emphasizing putting “it on the line” and creating work based on personal conviction, not external pressures like money, fame, or trendiness. He rejects societal codes, viewing them as conformist and creatively stifling.

Flamboyance and Showmanship

Milius acknowledges the role of “flamboyance” in Hollywood success, citing Francis Ford Coppola and Steven Spielberg as examples. He believes a flair for showmanship is necessary to thrive in the industry but stresses that true flamboyance must be rooted in genuine substance and purpose. He critiques Spielberg’s “roller-coaster ride” movies, finding them lacking in depth, while acknowledging Spielberg’s directorial skill.

Arnold Schwarzenegger as U.S. Marshal John Kruger in Eraser

Arnold Schwarzenegger as U.S. Marshal John Kruger in Eraser

Career Longevity and Anonymity

Milius reflects on career longevity, noting that he may be among the last screenwriters to amass a large body of work due to industry changes. He accepts the anonymity of rewrite work as a means to earn a living, finding satisfaction in crafting individual “riffs” within those assignments.

Mentoring and Community

Milius sees Hollywood as a “lonely place,” lacking in genuine mentorship and community among artists due to intense competition. He criticizes the Writers Guild for its perceived hostility towards him, feeling “blacklisted” and viewed as a “right-wing character.” Despite this, he embraces his outsider status, jokingly suggesting the Writers Guild should form a committee to “save and protect John Milius, the Yeti.”

Still a Dangerous Man?

In conclusion, when asked if he is still a “dangerous man,” Milius, while acknowledging his age, affirms his enduring “Yeti” spirit. Director John Milius remains a maverick, a figure whose outspokenness, unique vision, and dedication to his craft have left an indelible mark on Hollywood, even if he remains something of an outsider within its system. His legacy as both a writer and director is secure, built on a foundation of bold storytelling, uncompromising integrity, and a distinct, unforgettable voice.

Steven Spielberg

Steven Spielberg

This article was originally published in Creative Screenwriting volume 7, #2.