Stepping into the “Sargent and Fashion” exhibition at Tate Britain is like entering a world of undeniable technical brilliance, embodied by the portraits of Artist John Singer Sargent. Born in Italy to North-American parents, Sargent, a name as mellifluous as his brushstrokes, captured the elite of his era with a dazzling flair. His paintings, currently showcased in London, are a study in posing, posturing, and the sheer fabrication inherent in high-society portraiture. But beyond the shimmering surfaces, one is compelled to ask: do these portraits evoke genuine feeling, or are they, at their core, soulless representations of wealth and status?

The exhibition predominantly features portraits of women, crafted to please and flatter. Sargent’s clientele, unsurprisingly, consisted of the affluent – the nouveau riche and, less frequently, the aristocracy. His studio, located in the fashionable Tite Street, Chelsea, placed him squarely in the heart of London’s high society, even across the street from Oscar Wilde. This immersion in elite circles undoubtedly shaped his perspective and artistic focus.

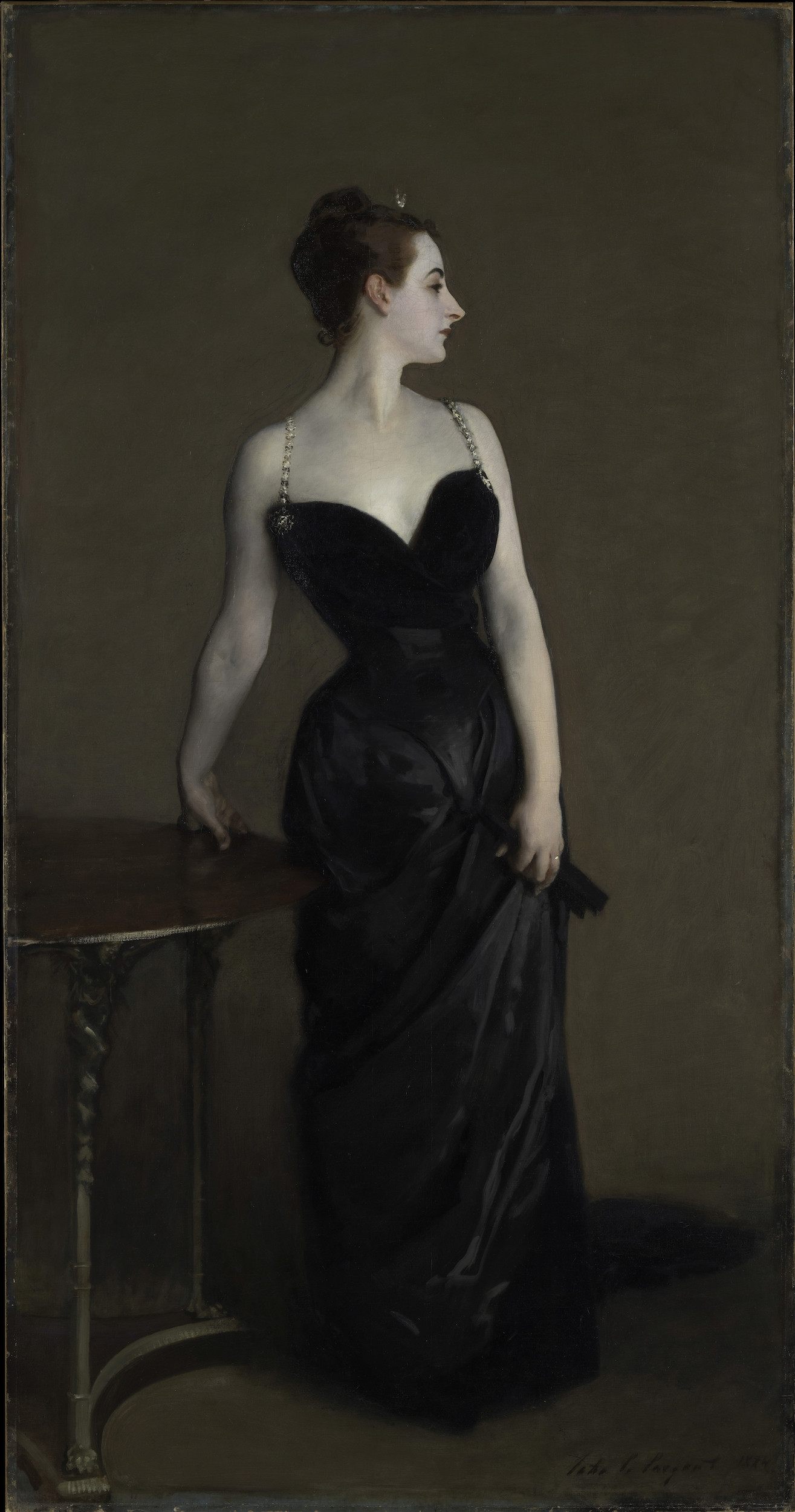

John Singer Sargent, “Madame X” (1883–84), oil paint on canvas; The Metropolitan Museum of Art (© The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence; all images courtesy Tate)

John Singer Sargent, “Madame X” (1883–84), oil paint on canvas; The Metropolitan Museum of Art (© The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence; all images courtesy Tate)

Reflecting on Sargent’s potential snobbery, one recalls an anecdote from his commission to paint the daughters of a Sheffield industrialist. In stark contrast to his usual subjects, Sargent’s disdain for this task is evident in an 1884 letter where he refers to painting “three ugly young women of Sheffield, dingy hole.” This reveals a stark contrast in his attitude towards different social classes, raising questions about whether his artistic approach was influenced by his personal biases. Were these Sheffield daughters truly less aesthetically pleasing than his usual aristocratic sitters, or was this a reflection of Sargent’s own social prejudices?

John Singer Sargent, “Lady Helen Vincent, Viscountess d’Abernon” (1904), oil paint on canvas; Collection of the Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama

John Singer Sargent, “Lady Helen Vincent, Viscountess d’Abernon” (1904), oil paint on canvas; Collection of the Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama

As a sought-after portrait artist, John Singer Sargent was deeply concerned with several key aspects of representation. Firstly, the sitter’s presentation within the canvas frame—their pose and posture. Secondly, the way they were draped or adorned, often reclining or standing in relation to fashionable furniture like a chaise lounge or a walking cane for dandies. Finally, and crucially, the opulent fabrics that clothed them. The exhibition cleverly displays original garments alongside their painted counterparts, inviting comparison between reality and Sargent’s artistic interpretation. These carefully arranged fabrics often served practical purposes, such as subtly concealing pregnancies, a common consideration for his society clientele. However, the face remained paramount – capturing the sitter’s most captivating and enduring image was always the ultimate goal.

Installation view of *Sargent and Fashion* at Tate Britain picturing “La Carmencita” (c. 1890) and her costume (c. 1890) (photo by Jai Monaghan © Tate)

Installation view of *Sargent and Fashion* at Tate Britain picturing “La Carmencita” (c. 1890) and her costume (c. 1890) (photo by Jai Monaghan © Tate)

However, artist John Singer Sargent‘s technical prowess wasn’t flawless. His recurring weakness lay in the depiction of hands. Often, they appear disproportionate – porcine, stubby, overly elongated, or with poorly defined fingers, sometimes even abruptly cut off. Did Sargent lack observation skills regarding hand anatomy, or was it a matter of indifference? Examining the right hand of “Madame X” (Virginie Gautreau), painted in 1883–84, reveals a disconcerting crudeness, almost “butchered” in its execution. This same awkwardness is noticeable in the hands of one of the “ugly young women” from Sheffield. Perhaps, in Sargent’s mind, the perceived social standing of his subjects influenced his attention to detail and care in execution.

John Singer Sargent, “Portrait of Miss Elsie Palmer (A Lady in White)” (1889–90), oil paint on canvas; Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center

John Singer Sargent, “Portrait of Miss Elsie Palmer (A Lady in White)” (1889–90), oil paint on canvas; Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center

John Singer Sargent, “Mrs. Hugh Hammersley” (1892), oil paint on canvas; The Metropolitan Museum of Art (© The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence)

John Singer Sargent, “Mrs. Hugh Hammersley” (1892), oil paint on canvas; The Metropolitan Museum of Art (© The Metropolitan Museum of Art/Art Resource/Scala, Florence)

John Singer Sargent, “Mrs- Carl Meyer and her Children” (1896), oil paint on canvas; Tate (photo © Tate)

John Singer Sargent, “Mrs- Carl Meyer and her Children” (1896), oil paint on canvas; Tate (photo © Tate)

John Singer Sargent, “Portrait of Ena Wertheimer: A Vele Gonfie” (1904), oil paint on canvas; Tate (photo by Oliver Cowling © Tate)

John Singer Sargent, “Portrait of Ena Wertheimer: A Vele Gonfie” (1904), oil paint on canvas; Tate (photo by Oliver Cowling © Tate)

The “Sargent and Fashion” exhibition at Tate Britain, running until July 7, curated by James Finch and Chiedza Mhondoro, offers a compelling exploration into the world of John Singer Sargent. It prompts viewers to consider the complexities of his art – the dazzling surface appeal versus the potential emotional depth, the technical mastery alongside occasional shortcomings, and the reflection of social hierarchies within his portraiture. It’s an exhibition that encourages a critical look beyond the glitter and glamour, inviting us to ponder the true essence of Sargent’s enduring appeal as a chronicler of his fashionable era.

The “Sargent and Fashion” exhibition is on view at Tate Britain (Millbank, London, England) until July 7, 2024.