In the summer of 1809, as John Quincy Adams prepared for his diplomatic mission to St. Petersburg, Russia, a significant chapter began not just for him and his career, but also for his sons, particularly John Adams Ii. Leaving his two eldest sons, George Washington Adams and John Adams II, behind in Quincy with family was a decision that weighed heavily, especially on his wife, Louisa Catherine. This separation marked a new phase in John Quincy’s relationship with his children, especially as it pertained to their education and upbringing from a distance. While previous absences during his time as a U.S. Senator had been shorter, this new appointment would stretch thousands of miles and several years, from 1809 to 1814.

From Russia, John Quincy Adams embarked on a new form of paternal guidance: letter writing. For the first time, he directly corresponded with his sons, eight-year-old George and six-year-old John Adams II. Previously, any communication had been brief notes tucked into letters addressed to their mother or grandparents. However, these new letters from Russia were substantial, mirroring his characteristic style – detailed, informative, and filled with paternal advice. Central to his messages was the emphasis on education, writing proficiency, and elegant penmanship – skills deeply valued within the Adams lineage. He impressed upon his sons, including John Adams II, the importance of purpose and direction in life, urging them to see themselves as having “some single great end or object to accomplish.”

Within these letters, John Quincy Adams consciously passed down a cherished family mandate: the meticulous practice of writing and preserving correspondence. This tradition, a cornerstone of Adams family history, originated with his own father, John Adams. In a letter to Abigail Adams dated June 2, 1776, the elder Adams lamented his past neglect of record-keeping and announced his commitment to documenting his letters in a folio book. This practice was quickly adopted and passed down to John Quincy Adams. As early as September 27, 1778, while in Europe, young John Quincy wrote to his mother Abigail, recounting how his father had instilled this very mandate in him. He acknowledged the “utility, importance, & necessity” of keeping a journal, though admitted his youthful struggle with the discipline required for consistent diary keeping.

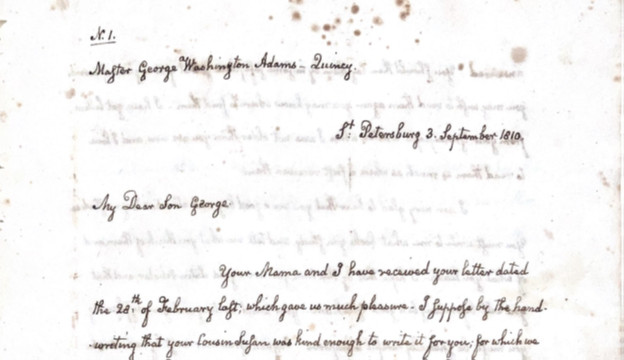

detail of a handwritten letter

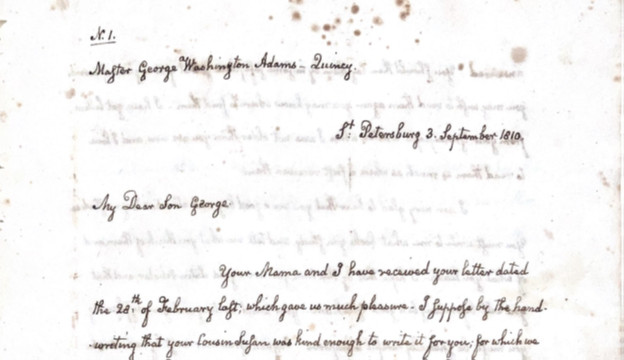

detail of a handwritten letter

John Quincy Adams’s letter to his son George Washington Adams, 3 September 1810, showcasing the detailed penmanship and structured communication he valued.

John Quincy Adams, understanding the importance of this family tradition, didn’t wait until John Adams II reached eleven to begin his instruction. Through his letters from Russia, he initiated his sons into this vital aspect of their heritage. He provided practical guidance, particularly to George Washington Adams, on managing their growing correspondence – a crucial element in preserving and organizing letters. The first step, he advised, was to diligently keep every letter received from their parents. Mirroring his own organizational habits, John Quincy instructed his son to number his outgoing letters. He explained, “I have therefore numbered this letter at the top, and will continue to number those that I shall write you hereafter— Thus you will know whether you receive all the letters that I shall write you, and when you answer them you must always tell me the number or the date of the last letter you have received from me—.” To ensure clarity, he suggested George consult his uncle, Thomas Boylston Adams, for further instruction on numbering, endorsing, and filing these important documents, and to store them safely for future reference.

While the detailed instructions were initially directed towards George, John Adams II was not excluded from this familial education. Upon receiving his first letter from John Adams II, John Quincy noted, “marked it down, number one, and put it upon my file.” Although he didn’t reiterate the step-by-step instructions, likely assuming George would share the knowledge, John Quincy held similar expectations for John Adams II. He anticipated letters that demonstrated improved penmanship and intellectual growth. He expressed his pleasure that John Adams II had “resolved to keep your own file,” and conveyed his hope for “an entertaining and instructive correspondence between us,” marking the beginning of their individual written dialogue.

detail of a handwritten letter

detail of a handwritten letter

John Quincy Adams’s letter to his son John Adams II, dated June 15, 1811, initiating his younger son into the Adams family tradition of correspondence, emphasizing penmanship and thoughtful communication.

Through these transatlantic letters, John Quincy Adams effectively extended his paternal influence, teaching the next generation of Adams men, including John Adams II, the enduring family tradition of writing, recording, and meticulously preserving their correspondence – a practice that would continue to define the Adams family legacy for generations to come.

The Adams Papers editorial project at the Massachusetts Historical Society gratefully acknowledges the generous support of our sponsors. Major funding of the edition is currently provided by the National Endowment for the Humanities, the National Historical Publications and Records Commission, and the Packard Humanities Institute.