John Belushi, a name synonymous with explosive comedy and raw talent, checked into Chateau Marmont on the night of February 28, 1982, a man teetering on the brink. Just 33 years old, he was a shadow of his former vibrant self – sweaty, disheveled, and visibly worn down. He requested his preferred bungalow, No. 3, a familiar haven from his Saturday Night Live days, unaware that this stay would mark the tragic final chapter of his life. The question of How Did John Belushi Die is one that continues to resonate, casting a long shadow over Hollywood and serving as a cautionary tale of fame, addiction, and self-destruction.

A Troubled Stay at Chateau Marmont

Belushi’s extended stay at Chateau Marmont that winter had already been turbulent. Initially residing in suite No. 69, he was forced to relocate after noise complaints from both sides – his music and late-night revelry clashing with neighbors bothered by the sound and Belushi himself irritated by a crying baby. A brief stint in penthouse No. 54 followed, cut short after a visit from his wife, Judy. Finding a quaalude on the floor, Judy’s concerned question, “Are you sure you want to stay here?” hinted at the deepening despair surrounding Belushi. He eventually settled into bungalow No. 3, bringing with him script drafts for Noble Rot, his planned romantic comedy set in California’s early wine industry, research materials, and a new stereo system – a facade of productivity masking a deeper turmoil.

Despite his outward intentions to write and create, Belushi was spiraling. Meetings with writers and development executives were unproductive, his manager Bernie Brillstein and Paramount Pictures executives grew increasingly concerned. Paramount, losing patience, even sent Michael Eisner to Chateau Marmont to pitch Belushi a new, less demanding project – a comedic adaptation of The Joy of Sex. However, it was evident to everyone around him that Belushi was profoundly unwell.

Signs of a Downward Spiral

Belushi’s behavior became increasingly erratic and alarming. His attention span vanished, replaced by constant, mysterious phone calls at all hours. Meetings were missed, or he arrived hours late, if at all. His bungalow descended into squalor, mirroring his personal neglect. Speech became scattered and incoherent, his clothes were perpetually dirty and rumpled, and basic hygiene seemed to be abandoned. Filmmaker Al Reinert, encountering Belushi in the hotel garage, described a disoriented figure pacing and muttering, his pupils “as black and dilated as wide-open camera lenses.”

John Belushi in The Blues Brothers, a film that achieved cult classic status but did not initially meet box office expectations.

John Belushi in The Blues Brothers, a film that achieved cult classic status but did not initially meet box office expectations.

Drug use was the unspoken, yet obvious explanation for Belushi’s decline. Known for his all-consuming nature, he indulged in food, alcohol, and drugs with the same unrestrained gusto he brought to his comedy. His legendary capacity for excess was often admired, even boasted about. However, this wasn’t performance anymore. Belushi had been consuming cocaine and marijuana daily for a long time and had begun experimenting with heroin, claiming it was “research” for a punk rock movie.

In the permissive atmosphere of early 1980s Hollywood, such behavior was often overlooked, as long as the income kept flowing. But Belushi’s career was faltering. Films like Continental Divide, Neighbors, and even Spielberg’s 1941 had bombed. The Blues Brothers, while later a cult hit, hadn’t initially justified its massive budget. Animal House, his last major success, was almost four years in the past – an eternity in Hollywood terms. He was jeopardizing his career, his choices painting a grim picture for even casual observers. One studio executive’s wife, after a disjointed meeting with Belushi at a nightclub, poignantly likened the situation to Sunset Boulevard, a film about a forgotten star, a comparison that resonated deeply despite the denial of her husband.

The Night Before: March 4, 1982

Concerned friends and colleagues, including his wife Judy and best friend Dan Aykroyd, desperately sought to intervene. They believed a return to New York, under their support, could help Belushi get clean and resume work. Aykroyd was even writing Ghostbusters as a project for them and Bill Murray. However, reaching Belushi became increasingly difficult. He moved erratically through nightclubs, homes, restaurants, and drug dens, often ditching hired limousines and disappearing with new acquaintances. In his bungalow, he was either too incapacitated to communicate or surrounded by enablers, making any serious conversation impossible. He was, as described, a wreck, drifting further from help.

Robert De Niro, also staying at Chateau Marmont while exploring film projects, occasionally crossed paths with Belushi. The two had known each other from New York’s downtown scene, sharing a history of late-night parties. De Niro, having experienced issues with rental homes in Hollywood, preferred the anonymity and convenience of Chateau Marmont, maintaining a penthouse suite.

John Belushi at Danny DeVito and Rhea Perlman’s wedding reception, showcasing his public persona even amidst personal struggles.

John Belushi at Danny DeVito and Rhea Perlman’s wedding reception, showcasing his public persona even amidst personal struggles.

Another image of John Belushi at the wedding reception, captured shortly before his tragic decline.

Another image of John Belushi at the wedding reception, captured shortly before his tragic decline.

One afternoon, De Niro brought his children to a party where they witnessed Belushi consuming alarming amounts of cocaine and heroin, leading to a disturbing scene of him excusing himself to vomit. Despite this, and his own cocaine use, De Niro continued to seek Belushi’s company after his children returned east. They would party together at the bungalow or in VIP sections of Sunset Strip venues, embarking on reckless sprees.

On Thursday, March 4th, De Niro and Harry Dean Stanton tried to reach Belushi, calling him from Dan Tana’s and On the Rox, urging him to join them. Unsuccessful in reaching him by phone, they went to Chateau Marmont. They found Belushi’s bungalow in disarray, not just messy, but trashed, suggesting a violent outburst. Adding to the unsettling scene was Cathy Smith, a woman De Niro described as “trashy,” lounging amidst the debris, seemingly at home in the chaos and with Belushi. De Niro, uneasy, left after Belushi suggested they return after the club closed.

De Niro returned to his suite with Stanton and two women, later receiving a call from Robin Williams. Williams, having encountered De Niro and Stanton at On the Rox, agreed to meet at Belushi’s after his comedy set at The Comedy Store. De Niro, already in his suite, suggested Williams visit Belushi alone. Williams did, and like De Niro, was disturbed by the atmosphere, leaving quickly after a brief conversation and a small amount of cocaine. De Niro also stopped by Belushi’s bungalow again, entering through the patio door, taking more cocaine from the table, and returning to his suite around 3 a.m.

Robert De Niro in 1982, around the time of John Belushi’s death, a friend and witness to Belushi’s final days.

Robert De Niro in 1982, around the time of John Belushi’s death, a friend and witness to Belushi’s final days.

The Morning of March 5, 1982: Discovery and Aftermath

At 8 a.m. on March 5th, a room service waiter delivered breakfast to Belushi’s bungalow. Cathy Smith signed for it, ate, cleaned up drug paraphernalia, checked on Belushi who was snoring loudly, and left. Later, music producer Derek Power, searching for Miles Copeland, knocked on Belushi’s door by mistake, receiving no response.

Around noon, Bill Wallace, Belushi’s personal trainer and bodyguard, walked to the bungalow with a typewriter in hand. Shortly after, Brillstein’s assistant, Joel Briskin, arrived in a suit, rushing. Then, paramedics and police arrived, followed by a media frenzy outside the hotel grounds.

A sunbather, noticing the unusual activity, inquired in the lobby and was told of a “slight disturbance.” The reality was far more tragic. Bill Wallace had found Belushi unconscious and unresponsive. CPR attempts failed. In Hollywood fashion, Wallace first called Brillstein, Belushi’s agent, not the police.

“I’m having trouble waking John up,” Wallace said, agitated. Brillstein initially thought Belushi was feigning sleep to avoid a meeting with Paramount executives. He instructed Wallace to wait, but Wallace called again, more urgently, “There’s something really wrong with John!” Brillstein’s secretary called a doctor who advised calling paramedics. Briskin was then dispatched to the hotel.

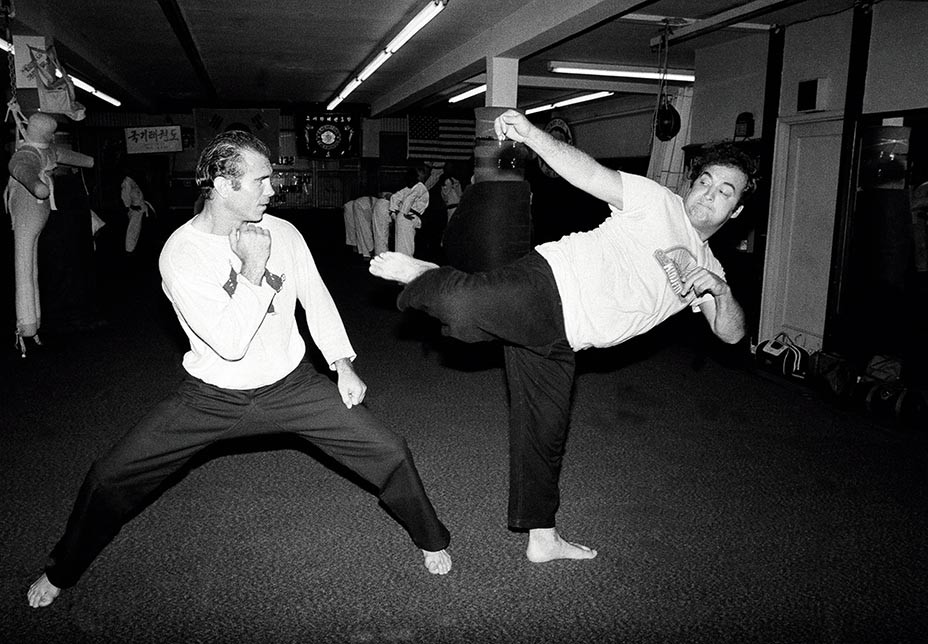

John Belushi with Bill Wallace, his trainer and bodyguard, who discovered him on the morning of his death.

John Belushi with Bill Wallace, his trainer and bodyguard, who discovered him on the morning of his death.

Briskin found Wallace weeping and performing mouth-to-mouth resuscitation. “Get out of here,” Wallace yelled, “John’s dead!” Paramedics confirmed it. They didn’t attempt defibrillation; Belushi was gone. Needle marks on his arms confirmed the cause: a drug overdose.

Brillstein, meanwhile, had driven to Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, expecting Belushi to be taken there. He alerted the staff to prepare for a major star requiring immediate care and privacy. He waited anxiously for news, only to receive the devastating call confirming Belushi’s death.

He then called Aykroyd, delivering the news directly, and instructed him to inform Judy before the media broke the story. Brillstein returned to his office to manage the fallout of a tragedy many had foreseen but failed to prevent.

The Immediate Aftermath and Media Frenzy

Chateau Marmont staff were unprepared for the unfolding crisis. General Manager Suzanne Jierjian was at a doctor’s appointment when the news broke. Returning to a scene of emergency vehicles and media, she was met by her assistant Tom Rafter with the sketchy news of Belushi’s death, the cause still unknown. Co-owner Ray Sarlot arrived, finding “bedlam,” with media swarming and the switchboard lit up.

De Niro, unable to reach Belushi by phone and noticing the commotion, called the front desk, his inquiries initially rebuffed. Demanding to speak to Jierjian, he was finally connected. Her vague but ominous responses, “There is a problem,” “It’s bad,” “It’s really bad,” led De Niro to the devastating realization. He dropped the phone and wept.

Sarlot focused on damage control, protecting other guests and the hotel’s reputation. Guards were stationed, directing media to the garage. Police barricades were set up, restricting access to Marmont Lane. Despite this, some media breached security. One camera crew even attempted to film De Niro at his suite, until he yelled “Go away!”

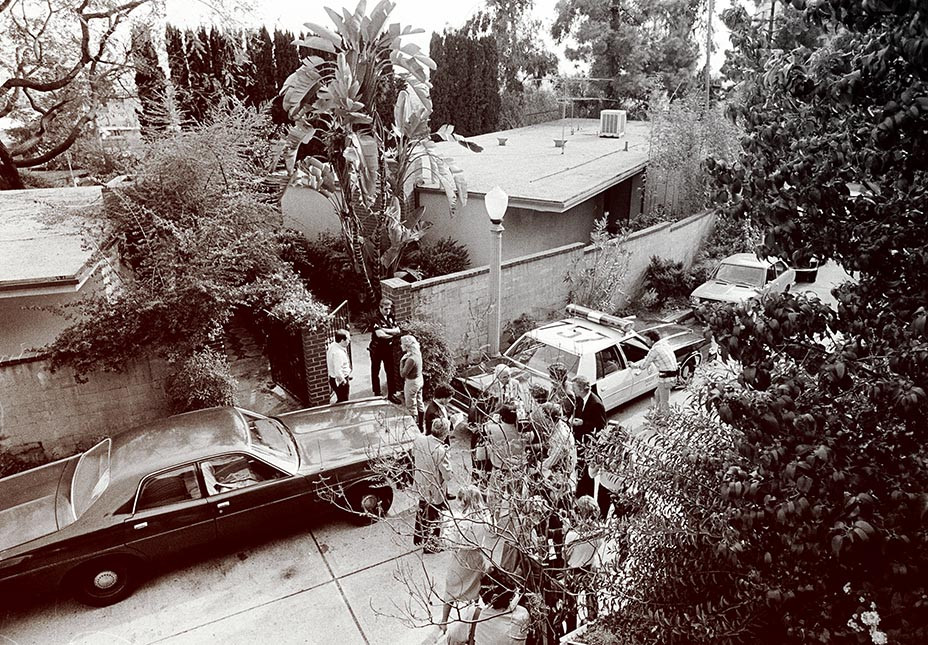

Police presence outside Bungalow 3 at Chateau Marmont, securing the scene after John Belushi’s death.

Police presence outside Bungalow 3 at Chateau Marmont, securing the scene after John Belushi’s death.

Remarkably, Sarlot and his staff managed to contain the situation, with many hotel guests remaining unaware of the tragedy unfolding nearby. Tony Randall, living next door to Belushi, reportedly remained oblivious until he saw the coroner’s wagon.

Belushi’s body was removed from the bungalow and taken to a coroner’s vehicle on Monteel Road, amidst a throng of media. Jierjian’s firm handling of the press even impressed a police lieutenant, who suggested she consider a career with the LAPD.

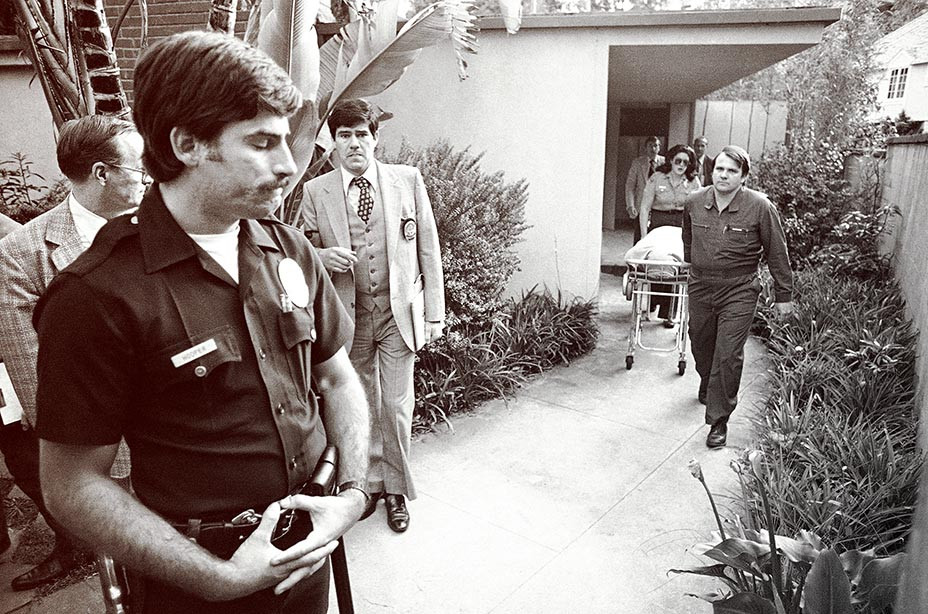

Officials removing John Belushi’s body from Chateau Marmont, marking the somber end to his life.

Officials removing John Belushi’s body from Chateau Marmont, marking the somber end to his life.

John Belushi’s body being transported from Bungalow 3, the final act in the tragic drama at Chateau Marmont.

John Belushi’s body being transported from Bungalow 3, the final act in the tragic drama at Chateau Marmont.

The Investigation and the Book “Wired”

The day after Belushi’s death, Brillstein retrieved Belushi’s belongings from the bungalow. Police had already searched the room, finding marijuana and cocaine residue. Brillstein was shocked by the squalor, describing it as “depraved.” He took a few personal items and a jacket to dress Belushi for his funeral. Chateau Marmont staff thoroughly cleaned and remodeled the bungalow, wanting to erase its association with the tragedy.

Bob Woodward’s 1984 book, Wired: The Short Life and Fast Times of John Belushi, further cemented the narrative of Belushi’s self-destruction. Based on extensive interviews, including with Cathy Smith, who later pleaded no contest to involuntary manslaughter for providing Belushi with the fatal drugs, the book was a bestseller but deeply controversial. Friends and family criticized its focus on drugs and excess, feeling it misrepresented Belushi’s talent and personality. Jim Belushi called Woodward a “cocksucker” and “motherfucker,” expressing disgust for what he felt was a cold and uncompassionate portrayal.

Chateau Marmont owners were offended by the book jacket’s description of the bungalow as a “seedy hotel bungalow.” They filed an $18 million defamation lawsuit, objecting to the characterization of their $250-a-night bungalow as “seedy.” They settled with the publisher, who changed the wording in later editions, clarifying that “seedy” referred to Belushi’s mess, not the hotel itself.

Legacy and Lasting Impact

Despite attempts to move on, John Belushi’s death became inextricably linked to Chateau Marmont. “Ghoul tours” of Hollywood landmarks began including the hotel as the site of his overdose. The tragedy became a defining feature of the hotel’s narrative, overshadowing its glamorous history for many. Even decades later, articles about Chateau Marmont routinely mention Belushi’s death. Jay McInerney’s anecdote of being told “Is it good? John Belushi died there!” when informed he would be staying at Chateau Marmont, highlights the enduring, albeit morbid, association.

The question of how did John Belushi die has a definitive answer: a drug overdose, a speedball of cocaine and heroin, administered by Cathy Smith. However, the deeper question of why John Belushi died is more complex, intertwined with the pressures of fame, the demons of addiction, and the tragic vulnerability of a brilliant comedic talent consumed by his own excesses. His death at Chateau Marmont remains a stark reminder of the destructive nature of addiction and the fragility of life, even in the glittering world of Hollywood.

Source:

Levy, Shawn. The Castle on Sunset: The History of the Chateau Marmont. Doubleday, 2019.