John Boorman, a name synonymous with cinematic innovation and daring storytelling, has been crafting feature films for an impressive half of cinema’s existence. As he himself noted, feature films are just over a century old, and his career spans more than fifty years of that history. While he has hinted at retirement, echoing the often-porous retirements of other auteurs, his legacy remains firmly cemented in the landscape of film history. His film Queen and Country, a poignant sequel to his autobiographical masterpiece Hope and Glory, serves not just as a potential swan song, but also a reflective return to his formative years, specifically his time in the British Army, a period that subtly ignited his lifelong passion for filmmaking.

Queen and Country immediately establishes this meta-narrative. The opening scene depicts a “dying soldier” who is revealed to be an actor on a film set. This playful blurring of reality and fiction culminates in the final shot: an 8mm camera, its mechanism winding down, symbolizing perhaps the end of a reel, a career, or an era. In contrast to Hope and Glory, where childhood innocence perceived the Blitz-stricken London as an adventurous playground, Queen and Country confronts a young man with the stark realities of adulthood: the rigid class structures of 1950s Britain and the grim consequences of the Korean War. The film masterfully blends the lightheartedness of service comedy with the weightier themes of emotional and sexual awakening, elements that transcend genre boundaries. Recent retrospectives rightly celebrate John Boorman’s profound impact on cinema, and Queen and Country stands as a compelling testament to his enduring artistry.

In an interview, John Boorman reflected on the long gestation of Queen and Country, stating, “Yeah, for a long time. In fact, after I finished Hope And Glory, I had in mind to do this story of my army career, as it were.” He elaborated on the personal connection, explaining how Hope and Glory‘s narrative arc, which saw his family relocate to Shepperton during the Blitz, stemmed from his mother’s childhood experiences during World War I. This idyllic Thames setting, a stark contrast to wartime London, was rooted in his mother’s fond memories of being sent to the river to escape Zeppelin bombings. Boorman initially considered telling his mother’s story and that of her sisters, alongside his own conscription narrative. While his mother’s story remained untold on film, his army experience eventually found its voice in Queen and Country.

The Thames, though briefly featured in Queen and Country, holds significant symbolic weight, providing a natural counterpoint to the regimented environment of the army barracks. The presence of rivers, a recurring motif throughout John Boorman’s filmography, from The Emerald Forest to Excalibur, is deeply personal. “You always have a river in my films, because I was brought up in that river,” Boorman explained. For him, rivers are potent metaphors for life’s continuous flow. He also highlights the almost magical interplay between film emulsion and moving water, a cinematic enchantment he finds equally present in digital filmmaking.

Perhaps John Boorman’s most iconic riverine film is Deliverance, where nature takes on a powerful, and menacing, role. When asked about exploring the duality of nature in Deliverance, Boorman responded, “Nature is both benevolent and malevolent, and the power of nature, whether it’s a tempest or a raging river, reminds us that we are really rather pathetic little fleas on the back of this planet. It cuts us down to size. I think that’s a very salutary thing to happen.” In Deliverance, however, the river served a more overt metaphorical purpose, representing nature under threat from human encroachment, destined to be dammed for urban conveniences. The mountain men in the film, in this context, become personifications of a vengeful nature, reacting against this violation.

The concept of myth and humanity’s place within a larger, often indifferent, universe is another recurring theme in John Boorman’s work. Myths serve as reminders of human insignificance against the forces of nature or the divine. Even in Hope and Glory, the young protagonist’s fascination with a toy Merlin figure foreshadows the mythical dimensions that permeate Boorman’s filmography, extending beyond overtly fantastical films like Excalibur and Zardoz and influencing his approach to personal narratives.

“There’s a mythic element in my work, and you might say a spiritual one,” Boorman acknowledged. He sees this element existing in tandem, sometimes in conflict, with naturalism. He recounted his BBC film, “I Dreamt I Woke Up,” as an exploration of this dichotomy. In this film, Boorman himself appears in a documentary-style setting, introducing his world, which then seamlessly transitions into a mythic realm represented by his alter ego, played by John Hurt. This interplay between the real and the mythical, the personal and the archetypal, is a hallmark of John Boorman’s distinctive cinematic voice. He acknowledges that this approach is not always successful, but when it coalesces, the result is undeniably powerful.

Reflecting on criticism, a frequent companion of any filmmaker’s journey, John Boorman, who also co-founded and edited the Projections series, demonstrates a nuanced perspective. While many filmmakers harbor adversarial feelings towards critics, Boorman seems to have developed a more detached, almost philosophical stance. “In the course of my career, I think almost everything that can be said about me, good and bad, has been said. You only remember the bad reviews. I can never remember the good ones.” He humorously recalls a one-line Time magazine review of Point Blank, succinctly dismissing it as “a fog of a film,” illustrating the sting of negative criticism, however concise.

Returning to the autobiographical thread in Queen and Country, John Boorman discussed the delicate balance between factual representation and narrative license when drawing from personal memory. “The relationship between memory and imagination is a very mysterious one. If you just tell someone the story of something that happened to you, you are applying imagination to memory.” His guiding principle was “truthfulness,” prioritizing emotional resonance over strict factual accuracy. He illustrates this with Sinéad Cusack’s casting as his mother in Queen and Country, emphasizing the importance of capturing the “spirit” of his mother, rather than merely impersonating Sarah Miles, who played the same character in Hope and Glory. Boorman affirms that while rooted in real events and people, the film is ultimately shaped by his subjective memory and artistic interpretation. Events like the clock theft and his arrest for “seducing a soldier” were drawn from his actual experiences, filtered through the lens of memory and narrative necessity.

Boorman’s research into the Korean War further informed the film’s themes. He expressed his dismay at the war’s origins, viewing it as “a series of blunders,” a sentiment that shaped the film’s underlying critique of military bureaucracy and the often-unquestioning march to war. However, he also wrestled with portraying this critique responsibly, given that young soldiers were being sent to fight. This internal conflict is reflected in the film’s nuanced portrayal of military service, acknowledging both its absurdities and its human cost. The character of the left-wing MP’s son who refuses to go to Korea and the subsequent suspicion directed at Boorman’s character for his perceived communist leanings are rooted in the political anxieties of the era.

The historical context of post-war Britain is central to Queen and Country‘s thematic depth. Boorman highlights the transformative period he depicted: “Five years after the war, there was still rationing, bomb sites were everywhere, and the older generation of soldiers hanging onto the idea of imperial Britain, and the greatest empire the world has ever known. Two-fifths of the Earth’s surface was British, and it was all about to go.” The film captures this pivotal moment of societal shift, the dismantling of the old imperial order and the gradual erosion of rigid class structures, giving the personal story a broader socio-political resonance.

This clash of ideologies is directly addressed in a scene where Boorman’s character is questioned by his superiors, unable to categorize him as either capitalist or communist. “I was a Fabian socialist,” Boorman explains, highlighting the prevalent left-wing sentiment among his generation as a rebellion against a deeply conservative society. The film also touches upon the social barriers of the time, illustrating the near impossibility of a relationship between an aristocratic woman and a working-class man, further underscoring the rigid social hierarchies being challenged and slowly dismantled in post-war Britain.

Contrasting the narrative approaches of Hope and Glory and Queen and Country, Boorman notes a shift in perspective. While Hope and Glory adopted the “innocent eye” of a child amidst war, Queen and Country focuses on the transition from childhood to adulthood. The protagonist in Queen and Country, though older, still retains a childlike quality at the film’s outset, symbolized by his river swimming. The tone is “much mellower,” reflecting a more mature and reflective perspective on personal history.

Boorman recalls a poignant scene in Hope and Glory where a young girl, having lost her mother in a bombing, is met not with sympathy but with a disturbing curiosity from other children, almost accusing her of fabrication. This scene, based on an actual event, reveals a raw, almost pre-psychological approach to trauma. “That was something that actually occurred. This girl was very unpopular. Nobody wanted to be her friend, but her mother being killed gave her status. She was suddenly important, and she enjoyed the importance of people coming up and talking to her like they hadn’t done before. In a way, that compensated her for her loss of her mother.” This anecdote underscores the film’s unflinching portrayal of childhood and the complex, sometimes unsettling, ways children process grief and trauma.

In Queen and Country, a military trial scene highlights the prevailing skepticism towards psychiatry in the 1950s British Army. The dismissal of a psychiatrist as a witness reflects the era’s attitude towards mental health, where psychological distress was often brushed aside with a “get over it” mentality. “They were always called ‘trick cyclists,’ the psychiatrists. That was the case. That was the attitude generally in the army. If anything was traumatic or stressful, they said, ‘Get over it, get a grip.’”

With Queen and Country potentially marking the end of his directorial career, John Boorman has had the opportunity to revisit his past work during recent retrospectives. His perspective on his older films is intriguingly detached. “They mostly seem to be made by someone else, the person I used to be. I sometimes feel a little bit phony to claim credit for the work of another man that I used to be. [Laughs.] At the same time, it allows me to look at them in a very dispassionate way. I don’t need to feel the constant pain of the mistakes that I can watch and see.” This distance allows for a more objective assessment of his oeuvre, free from the immediate pressures and anxieties of creation. He admits to rarely re-watching his films, a common practice among directors who spend so much time immersed in their creation during production.

However, Boorman’s detailed commentary tracks, such as the one with Steven Soderbergh for Point Blank, reveal a remarkable recall for the technical and artistic decisions made decades ago. “The technical things, I can remember absolutely.” He recounts a conversation with David Lean shortly before his death, where Lean expressed feeling like he was “just beginning to get the hang of it,” even after a lifetime of filmmaking. Boorman reflects on the contrasting approaches to filmmaking, from the “innocence” of early work to the calculated mastery of seasoned directors. He describes his own evolution towards meticulous planning, contrasting it with Kurosawa’s famously detailed pre-production and occasional need for “coverage” shots as a safety net. Boorman’s preference for shooting only what he intends to use emphasizes actor focus and performance intensity, creating a different dynamic on set. He shares an anecdote about a humorous exchange between Kurosawa and Lean regarding their respective shooting setups, highlighting the diverse approaches even among master filmmakers.

John Boorman acknowledges the influence of numerous directors on his work, paying tribute to Kurosawa and Hitchcock in Queen and Country and creating a documentary about D.W. Griffith. However, Michael Powell stands out as a particularly formative influence. “Well, Michael Powell had a huge influence on me. When I saw his films at 17, 18, I suddenly thought, ‘I didn’t know films could do this.’ That was tremendous.” He places himself within the continuum of cinema history, having known figures like Hitchcock, Fellini, Bergman, Lean, and Wilder, connecting his career to the very early days of film and Griffith’s foundational contributions to cinematic grammar. He explains Griffith’s invention of shot-reverse-shot editing as a constructed convention that creates the illusion of conversation. He recounts his experience living with the Xingu tribe in the Amazon, where he struggled to explain filmmaking to a shaman unfamiliar with moving images, ultimately finding common ground in the shaman’s understanding of trance and altered states of perception. “Maybe in kind of an atavistic way, film connects us to a past of trance.”

This connection between filmmaking and mysticism is further explored in Boorman’s portrayal of Merlin in Excalibur, a character who embodies both magic and a form of proto-science, a trickster figure whose abilities remain partially enigmatic even from a modern perspective. “Isn’t that the case with magicians? They’re always a mixture of fake and real, aren’t they?” He praises Nicol Williamson’s Merlin performance for its “combination of clumsiness and luminousness,” a complex portrayal that avoids simplistic archetypes. Despite studio reservations due to Williamson’s past film failures, Boorman insisted on casting him, trusting his intuition.

John Boorman’s filmography is populated with memorable, often unconventional, lead performances, from Lee Marvin in Point Blank to Marcello Mastroianni in Leo The Last and Sean Connery in Zardoz. He also includes Brendan Gleeson among these notable collaborations, highlighting Gleeson’s frequent appearances in his films, including a starring role in The General. Boorman asserts that he has rarely found actors “difficult,” emphasizing the importance of clear communication, mutual understanding, and creating a safe environment for performers, especially when they are taking risks. “Acting is very courageous to do, particularly if you’re taking risks. An actor really needs to feel safe, and once that is the case, they usually behave very well. And it’s never the best actors who cause trouble. It’s always the second- or third-rates, and then they’re usually insecure, so that comes out of an insecurity.”

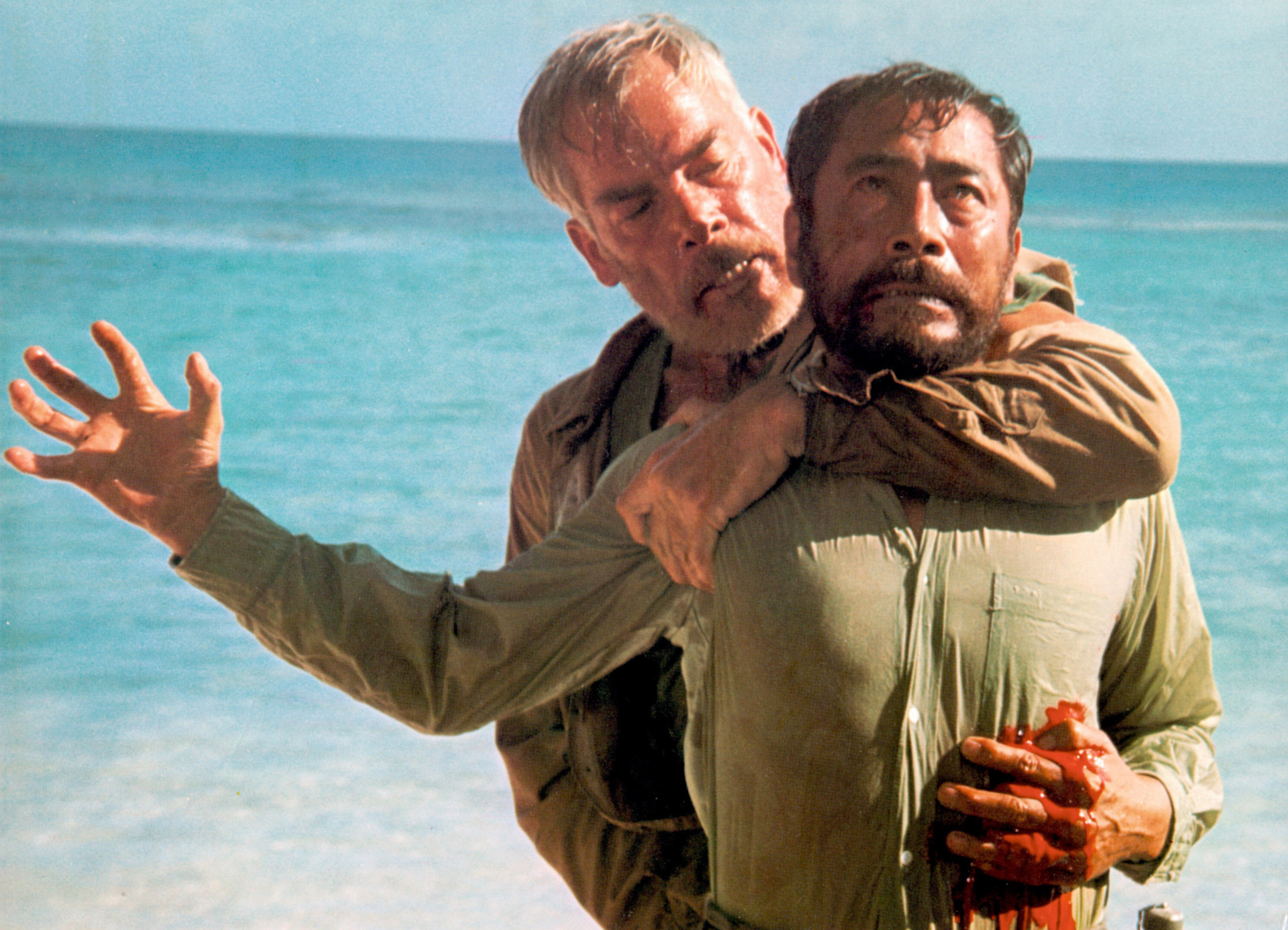

However, he acknowledges Toshiro Mifune as an exception, describing their collaboration on Hell In The Pacific as “a horrible experience.” The difficulties stemmed from a script misunderstanding and cultural clashes. Mifune was given a version of the script that transformed his character into a buffoonish samurai archetype, which clashed with Boorman’s vision. This led to constant corrections and a loss of face for Mifune, exacerbated by a Japanese crew. Despite these challenges and a serious illness that halted production, Mifune ultimately defended Boorman when producers considered replacing him, citing a matter of honor rooted in a sake toast they had shared.

In contrast to the fraught experience with Mifune, Lee Marvin’s support on Point Blank was crucial. “Lee Marvin really stuck his neck out for you on Point Blank, didn’t he?” Boorman confirms, recounting how Marvin, recognizing the film’s radical nature within Hollywood conventions, strategically deferred his script and casting approval to Boorman, effectively shielding him from studio interference. Marvin’s commitment extended throughout the production, despite his acknowledged alcoholism, which never impacted his work. Boorman shares a story of personal exhaustion during the Alcatraz shoot, where Marvin, sensing his director’s struggle, feigned drunkenness to alleviate pressure and allow Boorman time to resolve a scene staging issue. Marvin’s performance in Point Blank, like the film itself, is described as “sleek,” “physical,” and “slightly opaque,” perfectly synchronized with the film’s overall aesthetic. Even the art direction, with its bold color choices, initially raised studio concerns, with one executive fearing the film might be “unreleasable” due to its unconventional visual style.

Point Blank marked John Boorman’s first foray into color filmmaking after Catch Us If You Can in black and white. The film’s vibrant color palette, however, was far from conventional, drawing inspiration from the bold aesthetics of Godard’s Pierrot Le Fou. Boorman also notes the influence of Godard’s “intimate” and “cryptic” dialogue style on Point Blank.

Lee Marvin’s famous act of throwing the Point Blank script out a window reflects a broader filmmaking philosophy shared by John Boorman: a certain disregard for the script as a fixed, immutable text. When asked if this approach differs when he is the scriptwriter, as with Queen and Country, he responds, “No. Some people ask me if they can have my archive. And I say, ‘Well really, I don’t have that much.’ They say, ‘Well, you have scripts and things?’ And I don’t. I throw them away. The purpose of the script is a document to help you make the film. Once you make the film, the script has no value. These days, the Academy keeps sending me the scripts, and I never read them. I never even look at them. When I’m teaching, I always say, ‘Scripts should be written badly, because if they become a literary document, they get in the way. It’s just toilet paper.’” He cites Bergman’s scripts as examples of stark simplicity, prioritizing dialogue and essential action cues over elaborate descriptions, further emphasizing his view of the script as a practical tool rather than a literary end in itself.

Despite this apparent disdain for scripts as literary works, Boorman’s films are far from incoherent or self-indulgent, suggesting a mastery of visual storytelling and thematic coherence that transcends reliance on the written word alone.

Finally, John Boorman addresses the enduring cult following of Zardoz, a film initially deemed a failure but now considered a cult classic. “There’s a pretty fervent cult around Zardoz now.” He notes Fox’s decision to undertake a 4k restoration, driven by the film’s unexpected popularity. “My quote about it is that it went from a failure to a classic without ever passing through success.” While acknowledging the film’s flaws, possibly stemming from budgetary constraints, Boorman recognizes the retrospective appreciation afforded to films with the passage of time. He recounts the unconventional financing of Zardoz, secured through a gamble by his agent, David Begelman, who convinced Fox to greenlight the film based on a script read within a mere two-hour window, highlighting the often-precarious nature of filmmaking and the role of chance and audacious individuals in bringing unconventional projects to fruition.

John Boorman’s career, spanning decades and encompassing a diverse range of genres and themes, stands as a testament to his enduring vision and his profound understanding of the cinematic medium. From personal narratives to mythical explorations, his films consistently challenge conventions, provoke thought, and leave a lasting impression on audiences and filmmakers alike. Whether Queen and Country truly marks his final film or not, John Boorman’s contribution to cinema is undeniable and will continue to be celebrated for generations to come.