In the annals of American history, the name John Peter Zenger resonates as a pivotal figure in the fight for freedom of the press. While not a lawyer or politician, Zenger, a German immigrant printer in colonial New York, became the unlikely catalyst for a landmark legal battle that laid crucial groundwork for the First Amendment and the principles of free speech we cherish today. His trial in 1735, though not establishing immediate legal precedent, became a powerful symbol of defiance against governmental overreach and a beacon for journalistic independence in America.

To understand the significance of the John Peter Zenger case, we must delve into the political landscape of 18th-century New York. At the time, the Province’s only newspaper, The New York Gazette, was published by William Bradford, the public printer, and faithfully echoed the views of the Governor and his administration. This changed when Governor William Cosby, a figure known for his authoritarian style, removed Chief Judge Lewis Morris for issuing a dissenting opinion in a case. In response, Morris and his allies, prominent attorneys James Alexander and William Smith, established the New-York Weekly Journal in 1733. This marked the birth of independent journalism in the province. Alexander served as editor, and the Journal quickly became a platform for criticizing Governor Cosby, accusing his administration of tyranny and infringing upon the rights of the people through articles, satire, and lampoons.

Governor Cosby, determined to silence the dissenting voice of the New-York Weekly Journal, sought to shut it down. His administration targeted John Peter Zenger, the newspaper’s printer. The logic was simple: without a printer, the newspaper could not be published. Zenger, a skilled craftsman in a time when printers were few, became the focal point of Cosby’s crackdown. Daniel Horsmanden, a recently arrived English barrister, was tasked by the Governor to examine the Journal for seditious libel. Seditious libel, a charge rooted in English law, was defined as intentionally publishing criticism of public officials or institutions without legal justification.

Two grand juries were convened in 1734 to consider indicting John Peter Zenger for seditious libel. Despite the Cosby administration presenting evidence, both grand juries refused to indict Zenger. Undeterred, Governor Cosby then attempted to use governmental censorship to suppress the New-York Weekly Journal. He requested the Assembly to order the public burning of the newspaper’s issues by the hangman, a symbolic act of repression reminiscent of Tudor and Stuart England. However, the elected Assembly, reflecting popular sentiment, refused to comply. Cosby’s Council then ordered the sheriff to burn the papers publicly. Yet, when the sheriff sought authorization from the Court of Quarter Sessions, the court adjourned without issuing the order, effectively thwarting the public burning. In a workaround, the sheriff, with loyal officials present, had his servant burn the papers privately.

Frustrated by these setbacks, the Cosby administration resorted to a highly unpopular legal maneuver: prosecution by information. This allowed Attorney General Richard Bradley to proceed against Zenger without a grand jury indictment. Bradley filed an information before the Supreme Court of Judicature, where Cosby’s allies, Chief Justice James De Lancey and Justice Frederick Philipse, presided. They issued a bench warrant, and on November 17, 1734, John Peter Zenger was arrested and imprisoned in New York’s Old City Jail.

Zenger’s attorneys, Alexander and Smith, immediately sought a writ of habeas corpus. Zenger was brought before Chief Justice De Lancey, who set an exorbitant bail of £400, far beyond Zenger’s financial means. Unable to secure bail, Zenger remained jailed, awaiting trial. Despite his imprisonment, Zenger’s wife, Anna, and his apprentices bravely continued to publish the New-York Weekly Journal, further galvanizing public support for Zenger’s cause.

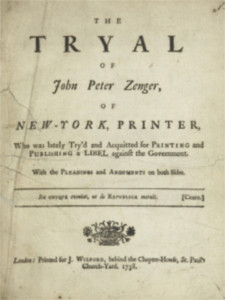

Cover page of The Tryal of John Peter Zenger

Cover page of The Tryal of John Peter Zenger

Defending John Peter Zenger against seditious libel presented significant legal hurdles. Under the prevailing law, the truth of the published statements was irrelevant. The jury’s role was limited to determining if Zenger was responsible for publishing the allegedly libelous material. If they found him responsible, Justices De Lancey and Philipse, Cosby’s staunch allies, would then decide if the content constituted seditious libel.

At Zenger’s arraignment in April 1735, his attorneys challenged the very legitimacy of the court. They argued that Governor Cosby’s removal of Chief Justice Lewis Morris was unlawful, rendering De Lancey’s appointment invalid. They further questioned the commissions of all judges, as they served “at the Governor’s pleasure,” suggesting a lack of judicial independence. The court, predictably, rejected these arguments. Chief Justice De Lancey famously declared, “You have brought it to that point that either we must go from the bench or you from the bar.” When Alexander and Smith refused to retract their challenges, the court disbarred them on April 16, 1735, leaving Zenger without legal representation.

In a surprising turn, the court appointed John Chambers, a young lawyer and Cosby loyalist, to defend Zenger. However, Chambers proved to be a more effective advocate than expected. He successfully challenged the jury selection process twice, ensuring a jury that was not overtly biased against Zenger. The jury included Thomas Hunt (Foreman), Harmanus Rutgers, Stanley Holmes, and other notable men of the time.

Chief Justice De Lancey adjourned the court until August 4, 1735, granting Chambers time to prepare. This delay allowed Zenger’s supporters to enlist the services of Andrew Hamilton, a preeminent attorney from Philadelphia. When the trial commenced on August 4 in City Hall, Attorney General Bradley presented the “information.” John Chambers entered a “not guilty” plea for Zenger and outlined the prosecution’s burden of proof. Then, in a dramatic move, Andrew Hamilton rose and preempted Bradley’s case by admitting that Zenger had indeed published the Journals.

Hamilton shifted the focus from publication to truth and liberty. He argued that the jury had the right to determine not only if Zenger printed the words but also if those words were libelous – and crucially, if they were true. In his powerful closing argument, Hamilton implored the jury to consider the broader implications of the case:

The question before the Court and you, Gentlemen of the jury, is not of small or private concern. It is not the cause of one poor printer, nor of New York alone, which you are now trying. No! It may in its consequence affect every free man that lives under a British government on the main of America. It is the best cause. It is the cause of liberty.

Despite Chief Justice De Lancey’s instructions that the jury should only decide if Zenger had published the Journals, the jury, after brief deliberation, delivered a stunning verdict: “not guilty” of seditious libel. Cheers erupted in the courtroom. Andrew Hamilton was celebrated as a hero, honored with a dinner and a cannon salute upon his departure. John Peter Zenger was freed the next day, returning to his printing business and publishing his own account of the trial, which further amplified the case’s impact.

While the John Peter Zenger trial did not immediately change the legal definition of seditious libel, its impact on public opinion and the burgeoning concept of freedom of the press was profound. It demonstrated the power of juries to act as a check on executive power and highlighted the growing independence of the legal profession in the colonies. The Zenger case became a symbol of the fight against censorship and a vital step toward the protections enshrined in the United States Constitution and the Bill of Rights. As Gouverneur Morris aptly stated, the Zenger case was “the germ of American freedom, the morning star of that liberty which subsequently revolutionized America!” The courage of John Peter Zenger and the brilliant defense by Andrew Hamilton resonated deeply, shaping the future of free speech and journalistic freedom in the United States.

Sources

Paul Finkelman. Politics, the Press, and the Law: the Trial of John Peter Zenger in American Political Trials Michal R. Belknap (ed). Connecticut (1994)

Donald A. Ritchie. American Journalists: Getting the Story. New York (1997)

Eben Moglen. Considering Zenger: Partisan Politics and the Legal Profession in Provincial New York, 94 Columbia Law Review 1495 (1994)