We often believe we perceive others accurately, but reality is frequently more nuanced. In my early days of ministry, I recall consciously avoiding a stern, traditional member of the congregation. Yet, as interaction became unavoidable, my initial apprehension transformed into respect and genuine fondness. Conversely, a long-term professional acquaintance recently surprised me with a deeply critical public remark, revealing an unexpected and less charitable perspective. These experiences highlight a fundamental truth: our perception is filtered, and we rarely see people as they truly are. This limitation isn’t new. The complex relationship between two prominent 17th-century Puritan theologians, John Owen and Richard Baxter, serves as a powerful historical example of how easily misunderstanding and misjudgment can take root, even between individuals with shared beliefs and goals.

Seventeenth Century Disagreement: Owen and Baxter’s Divergence

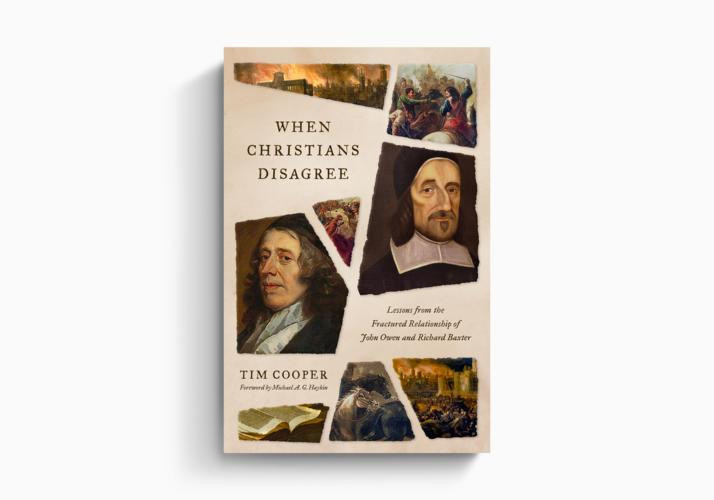

John Owen (1616-1683) and Richard Baxter (1615-1691) were contemporaries, both influential Puritan ministers in 17th-century England. They shared a commitment to Reformed theology and a desire for a more godly society. Given their common ground, one might expect them to be allies. However, history reveals a different story, one marked by increasing animosity. As explored in Tim Cooper’s book, When Christians Disagree: Lessons from the Fractured Relationship of John Owen and Richard Baxter, their relationship became deeply strained, offering valuable lessons about interpersonal conflict and the dangers of biased perception.

Several factors contributed to the rift between John Owen and Richard Baxter. Their contrasting personalities played a significant role. Owen, known for his intellectual rigor and theological depth, was also perceived as proud and sensitive to criticism. Baxter, while equally dedicated, possessed a more pragmatic and pastoral approach, sometimes leading to what Owen considered theological compromises. Furthermore, Baxter publicly critiqued some of Owen’s theological positions early in their acquaintance. Even though Baxter’s critique was relatively mild for his standards, Owen, who did not take criticism lightly, especially public theological disagreements, viewed this as an affront.

When the two men met in 1654 as part of a group advising Parliament on religious matters, their initial impressions were quickly solidified and worsened. Baxter observed Owen’s influential role within the group, interpreting it as arrogance. Owen, in turn, likely viewed Baxter as the irritating critic he had encountered in print. Their personal interaction, instead of bridging the gap, reinforced their pre-existing negative assumptions. This dynamic echoes the observation of Joseph Caryl, a contemporary Puritan, who noted in The Moderator that “the person who does not confide in his neighbors hinders them from confiding in him, and he that fears others creates in them a fear against himself.” This lack of initial trust and burgeoning suspicion poisoned the well of their relationship from the outset.

The 1659 Coup and the Unpardonable Sin in Baxter’s Eyes

The relationship between John Owen and Richard Baxter reached a breaking point in 1659. Owen was then serving as chaplain to key army leaders who orchestrated a coup d’état, effectively dismantling the republican government under Richard Cromwell, Oliver Cromwell’s son. Baxter had placed considerable hope in Richard Cromwell for furthering religious reform in England. Cromwell’s downfall shattered Baxter’s aspirations.

Baxter attributed the blame squarely to John Owen. While Owen was indeed connected to the events, his actual influence was likely overstated by Baxter’s perception. Owen himself was reportedly dismayed by the eventual outcomes of the political upheaval. However, fueled by secondhand information and his pre-existing negative view of Owen, Baxter concluded that Owen was responsible for derailing the godly reformation in England.

This conviction became entrenched in Baxter’s mind for the rest of his life. The consequences were significant. John Owen and Richard Baxter were leading figures during a period of intense persecution for Puritans who dissented from the established Church of England. Their division prevented a united front. Where their combined influence could have strengthened the Puritan cause against state pressure, their animosity undermined their collective efforts. Baxter’s distorted perception, his “filter” of mistrust toward Owen, had lasting detrimental effects.

Lessons in Perception and Christian Charity from Owen and Baxter

The fractured relationship between John Owen and Richard Baxter offers a sobering lesson for contemporary Christians and anyone navigating interpersonal relationships. It is remarkably easy to allow minor offenses and perceived slights to accumulate, ultimately distorting our view of another person through a “prism of hurt and offense.” We must be vigilant against this tendency.

Reflecting on the Owen-Baxter dynamic encourages self-examination in our own interactions. When faced with disagreement or perceived wrong, cultivating the “fruit of the Spirit”—love, peace, patience, kindness, gentleness, and self-control—becomes paramount. While maintaining healthy boundaries and discernment is necessary, we should resist allowing isolated incidents to define entire relationships. Like the author’s experience with his professional acquaintance, we may be surprised by unexpected actions, but we should strive to avoid letting these moments completely reshape our understanding of individuals.

The example of John Owen and Richard Baxter reminds us of the importance of generous interpretation, open communication, and a commitment to Christian charity, even amidst disagreement. Only by actively combating our inherent biases can we hope to see others more clearly and foster unity rather than division. Their story is a powerful call to cultivate understanding and empathy, ensuring that when we encounter the worst in others, it brings out the best in ourselves.

[ Tim Cooper (PhD, University of Canterbury) serves as professor of church history at the University of Otago in New Zealand. He is the author of John Owen, Richard Baxter and the Formation of Nonconformity and an editor of the Oxford University Press scholarly edition of Baxter’s autobiography.]