On a seemingly ordinary Friday afternoon, my ride through Colonial Williamsburg felt like stepping back in time, past quaint wooden trash bins and rustic sheep pens. My destination, however, was decidedly modern, an address recently tweeted by John Hinckley Jr.—the name forever linked to the attempted assassination of President Ronald Reagan in 1981. Leaving the historic charm behind, I found myself on a mundane commercial strip, eventually arriving at a modest, whitewashed building. I was on a quest to find Hinckley’s nascent record store, a venture he’d announced online with a “grand opening” supposedly just weeks away.

Initially, Hinckley was nowhere to be seen. The location was a typical, unassuming strip mall: a tax service, a familiar Domino’s Pizza, and a small Spanish church. A young man, seemingly a delivery driver, jumped into his pizza-branded car, complete with a prominent Jesus bumper sticker. A couple of cars idled at the nearby Hardee’s drive-through. The scene felt strangely surreal. Could this be the place where the man who once shot a president was setting up shop? Nestled between a vacant party supply store and a darkened Jazzercise studio? Had history relegated him to this unassuming spot?

Photograph of a desolate strip mall in Williamsburg, Virginia, featuring a Domino’s Pizza and other small businesses, hinting at the unexpected location of John Hinckley’s potential record store.

Fear wasn’t my primary emotion at the prospect of encountering John Hinckley Jr., a figure synonymous with 20th-century lone-gunman notoriety. In 2016, after more than three decades of court-mandated psychiatric care, a federal judge deemed Hinckley rehabilitated and released him into his mother’s care. He lived under legal constraints for several years until 2022, when all restrictions were unconditionally lifted. For the first time in 41 years, John Hinckley was completely free. With this newfound liberty, he chose an unconventional path: a creative life in the public eye.

Today, John Hinckley’s presence is primarily online: through his songs on YouTube, his eBay store selling paintings of his cat, and his active social media. Notably, he tweeted a message of peace after Donald Trump’s attempted assassination, stating, “Violence is not the way to go. Give peace a chance.” Hinckley also made headlines with his attempted “Redemption Tour” in 2022, a series of planned concerts across the country that were ultimately canceled due to widespread public disapproval. He then declared himself a “victim of cancel culture,” a sentiment that resonated online and fueled further discussion about John Hinckley’s place in public life.

The unease surrounding the Redemption Tour stemmed from its perceived attention-seeking nature. The reality was, a 67-year-old Virginian’s YouTube serenades would likely go unnoticed if not for his infamous past. His notoriety, born from an act of violence against a president, seemed to be the very currency he was attempting to trade for concert tickets. This ambition echoed the disturbing motivation behind his crime. Hinckley’s shooting of Reagan wasn’t politically driven; it was a desperate act to gain notoriety, to become famous like Jodie Foster, the actress he was obsessively fixated on. The Redemption Tour, therefore, felt like a chilling continuation of this impulse, raising concerns about where such attention-seeking might lead.

However, the idea of John Hinckley opening a record store felt different – a surprising turn towards humility. Becoming a small business owner, a purveyor of music in a modest shop outside Colonial Williamsburg, seemed to be a significant downshift from grand stages and national tours. With his own space, Hinckley could, at the very least, engage with an audience without the fear of constant cancellations. Ideally, it could become a haven for him, a place to share his passion for music and build a life centered around it, a dream he held even before the events of 1981.

Perhaps this was the reason I was drawn to Williamsburg. This iteration of Hinckley’s “redemption” felt more authentic, a quirky passion project representing a modest hope for a third act – something rarely afforded to someone with his history. Yet, it also carried a sense of fragility. The odds are stacked against any small business, and this venture felt particularly vulnerable.

The tweeted address for John Hinckley’s record store lacked a specific suite number, so I began my search at one end of the strip mall. I peered into a darkened boxing gym, the empty expanse of the Jazzercise studio, and a small church adorned with artificial flowers. Then, a prominent red “for rent” sign caught my eye, hanging in the grimy window of a vacant storefront. “This must be it,” I thought, “the future record store.” I knocked, but received no response.

Moving to the adjacent unit, an unmarked business with a pristine stainless-steel kitchen, a man answered my knock. Identifying myself as a reporter, I was met with an immediate, “Oh, are you here about Hinckley?”

This was Chris Waller, owner of a food truck, preparing to open a smashburger restaurant. “Never met him, never seen him,” Waller admitted about his rumored neighbor, John Hinckley. However, he was aware of the record store from a news article his father had sent, assuming many others had read it as well. “Traffic has been crazy lately,” he noted. “Definitely more cars around here in the past few days.”

“How do you feel about him moving in?” I inquired.

“Rather not say,” was his guarded reply.

“Would you buy records from him?”

“No, but I don’t own a record player. Besides, most music stores are struggling with streaming and all that.”

Waller offered a helpful tip: the “space available” sign had recently been removed from the former party supply store a few doors down. He suspected that was the location Hinckley had leased. To confirm, he suggested contacting the landlords, Extra Space Storage, located at the end of the strip mall, who apparently owned the entire property.

A quick YouTube search for “John Hinckley” yields a diverse range of content: news reports, documentary excerpts, and a video from Hinckley himself, titled “John Hinckley Speaks About Peace and Harmony,” recorded after the attempted assassination of former President Trump. “I know I’m known for an act of violence,” Hinckley states in the video, “but I live a peaceful life now.” With a monotone delivery, he encourages viewers to “try and reject violence in all its forms.” The video is simple and unpolished; the camera angle is low, and the reflection of a computer screen glints off his dark sunglasses. A top comment aptly summarizes the sentiment: “This is the strangest fucking timeline the world could’ve possibly ever gotten.”

John Hinckley’s YouTube channel is largely dedicated to his music. There he is, somewhat stout and pale, with thinning white hair, singing dozens of melancholic songs into his computer microphone while strumming a caramel-colored acoustic guitar, his name emblazoned on it in white block letters. His music is reminiscent of classic Americana, the kind you might hear in a coffee shop. Earnest and traditional, his voice is generally on key.

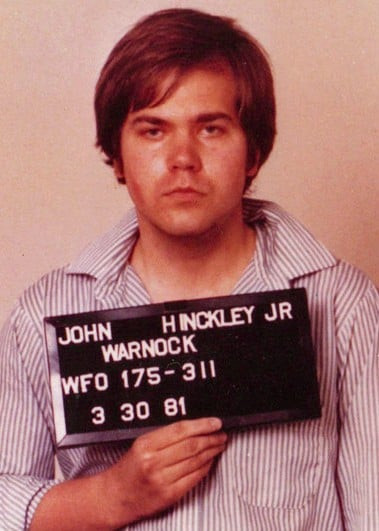

Hinckley’s lyrics, often straightforward and introspective, reveal a recurring plea: “I got through the darkest night / Now I hope to make things right,” or “You never thought I’d be free / You don’t know a different side of me.” Occasionally, in videos where he removes his sunglasses, glimpses of the young man from his mugshot emerge: the light eyes, arched eyebrows, and snub nose. In one video, the echo of that younger John Hinckley sings, “Tomorrow is another day / The best is yet to come / I have found a different way / It’s baffling to some.”

John Hinckley Jr.’s FBI mugshot, a stark reminder of his past and the public perception he grapples with in his attempts at redemption.

“Redemption” is a central theme in the John Hinckley narrative – the name of his ill-fated tour and his debut album. On his website, he even refers to the “National Redemption Party” as the “political wing” of his fan community. Redemption holds multiple meanings: religious cleansing of sin, reclaiming something owed. For John Hinckley, “My definition of redemption is to make amends for all the negativity that I created in 1981,” he stated in a New York Times Magazine interview. “I’m trying to redeem myself through positive music, through a thing that people really like—as opposed to the things they really hated about me in 1981.”

Hinckley’s actions since his release have tested public perceptions of justice. He targeted a globally prominent figure and injured three others, yet gained freedom. While some see this as the legal system functioning as intended – rehabilitation and reintegration – others view it as a systemic failure. Reagan’s daughter, Patti Davis, has expressed this sentiment, describing the shooting as “a shredded nerve that will never heal.” Davis opposed Hinckley’s release, and even for those who supported it, the question of his music career remains complex. Is it consistent to grant Hinckley freedom but deny him the pursuit of fame?

In 2022, when Hinckley announced his Redemption Tour, I explored local DC music venues’ hypothetical willingness to book him. Bill Spieler of DC9 was firmly against it, recalling the city’s fear in 1981. However, Sandra Basanti of Pie Shop remained open, emphasizing not “demonizing people who have a history” and believing in second chances after serving time. Dante Ferrando of the Black Cat focused on Hinckley’s music, suggesting a booking decision would depend on its quality, noting the little he’d heard “sounded like music. I mean, it sounded like something that would be a legitimate submission.”

These varied responses highlight the moral ambiguity surrounding John Hinckley. He embodies a persistent societal dilemma: an unresolvable riddle, a ghost that cannot be banished. Is his music a genuine attempt to honor his freedom, or a misuse of it? Does he owe it to the public to remain obscure, or, having served his time, is he entitled to seek amends and a new path?

Perhaps the question of what John Hinckley owes society is no longer relevant. Maybe, having paid his debt, he deserves to be judged on his present actions, as an individual separate from his past.

On my way to Extra Space Storage, I made a detour to the local Domino’s, curious about employee perspectives. A woman preparing pizza dough knew nothing of a record store, but seemed more amused by the impracticality of the venture than by John Hinckley’s involvement.

“People still buy records?” she wondered. “Good for them.”

“I really don’t care if he has a past,” she continued. “If we don’t let them work, how are they truly going to be rehabilitated?” However, she doubted the store’s viability, observing the lack of activity and questioning the timing: “It would seem dumb to open after Christmas, because I would think your sales would not be that great.”

Before I left, she paused, “Wait, so he assassinated JFK?”

Around the corner, I found the Extra Space Storage office. The young employee at the desk initially gave his full name but later asked for anonymity, citing his wife’s discomfort with his conversation about John Hinckley. He had likened Hinckley opening a record store to “the Green River Killer setting up a daycare” and declared he would not be a customer.

This employee lacked information about storefront rentals but provided the contact for the commercial leasing manager who could confirm if Hinckley was indeed leasing the party store space. Before calling, I decided to check the location myself, hoping to find John Hinckley actively setting up his shop.

Photograph of the “Parties Galore, Cakes & More” storefront, potentially John Hinckley’s intended record store location, appearing deserted and unprepared for opening.

Next to Domino’s, the colorful “Parties Galore, Cakes & More” sign still hung prominently. Peering through the window, I saw a small, sage-green front room with festive blue and pink stripes at waist level. Beyond, the interior revealed unusual architectural details: a back room with saloon doors, cabinetry visible through a wall cutout. A faded American flag stood tattered out front, perhaps 20 feet from the entrance.

Despite Hinckley’s now-deleted tweet claiming an imminent grand opening, the storefront was completely empty, devoid of any sign of activity. No records, no decorations, not even basic furniture. Standing in the cold, a sense of unease washed over me. Had I underestimated the possibility that the record store was just a fantasy, never intended to materialize?

Close-up photograph of the deserted storefront window, emphasizing the lack of preparation for a record store opening and raising questions about the reality of John Hinckley’s plans.

For years, John Hinckley was prohibited from speaking to the press, partly to manage his grandiosity and for his own protection. Excessive attention was considered detrimental to his delicate reintegration. While this restriction has been lifted, the ethics of a reporter pursuing a story about the erratic business plans of a man with mental illness, sequestered for decades, remained. I acknowledged this concern before even boarding the train to Williamsburg. Yet, I proceeded, justifying it with the possibility that this record store could offer him a fresh start. But, truthfully, I was also there to extract content from a clinically complex individual whose past would always overshadow his future.

Since Hinckley wasn’t present, emailing him for comment was the next step, though a response seemed unlikely. However, that evening, on the Amtrak back to DC, an email from John Hinckley appeared in my inbox. The record store was “on hold.” His initial plan was to sell his collection of approximately 1,000 rock albums and some guitars. However, the public backlash to his announcement made him “uncomfortable opening a store when there was such a negative reaction.” The landlord from Extra Space Storage never returned my calls, but later, a company spokesperson confirmed via email: “I can confirm John Hinckley expressed an interest in renting the property, but that’s where his interaction with us ended. There was no lease agreement finalized.”

Reflecting on the demise, or at least postponement, of John Hinckley’s dream, I recalled a conversation at a nearby Family Dollar while waiting for an Uber. Shemica Parker, the manager, a slender woman wearing gold necklaces and a festive “Merry Christmas” shirt, had a different perspective. When asked about John Hinckley potentially opening a store nearby, she responded, “To be honest, I’m a people’s person, I love everybody.” Would she buy his records? “If his music is good, I would,” she said, pulling up his YouTube channel on her phone.

Over the store’s speaker, Hinckley’s song “Lonely Dreamer” began to play. We listened in silence, surrounded by everyday items – cold medicine, gift cards, and holiday candy. As Hinckley sang about dreaming and overcoming hardship, Parker nodded and smiled. “I like this type of music,” she said. “A couple of months ago, I was going through something—a terrible, terrible situation. I was alone and daydreaming and sitting there just thinking and thinking and thinking. And once you listen to music like this, it relaxes you.”

Parker acknowledged Hinckley’s unexpected musical talent and we briefly discussed his life’s trajectory: the shooting, the insanity plea, the hospitalization, and his challenging pursuit of redemption. “People go through things,” Parker said. “Some things happen when you go through life. He did the crime, and he did the time, so now just give the man a second chance.”

Perhaps that second chance will eventually come. However, John Hinckley’s final emails conveyed a sense of resignation. He expressed continued hope to open his record store someday, in a location “safe for [him] and the public.” But for now, he wrote, “I’ll just keep selling records online.”

More: John Hinckley Jr.Record Stores

By Sylvie McNamara, Staff Writer