John Hodgman, celebrated author, humorist, and podcast host of Judge John Hodgman, offers a unique and insightful perspective on Frank Herbert’s Dune in a candid conversation. From his early encounters with the novel as a teenager to his thoughts on David Lynch’s controversial 1984 film adaptation and the unrealized visions of other directors, Hodgman’s journey with Dune mirrors the complex and enduring legacy of this science fiction masterpiece. This exploration into Dune through the lens of John Hodgman reveals not just a movie critique, but a personal narrative interwoven with fandom, film history, and the very nature of adaptation itself.

A Teenage Encounter with Dune and David Lynch’s Vision

Hodgman’s first attempt to conquer Dune coincided with the summer of Ghostbusters in 1984, a time when the David Lynch movie adaptation loomed on the horizon. As a 13-year-old more attuned to “Leonard Maltin’s history of animated film” than sprawling science fiction epics, the book initially proved daunting. “I’m trying to read this book and I’m like, ‘Oh, I’m sorry, this is boring. I want the spaceship please, but you’re giving me 7,000 words on the drug habits of worms in the desert and a hugely complex, subtle, political drama.'” This initial struggle highlights a common challenge for many readers encountering Dune‘s dense world-building and intricate plot for the first time.

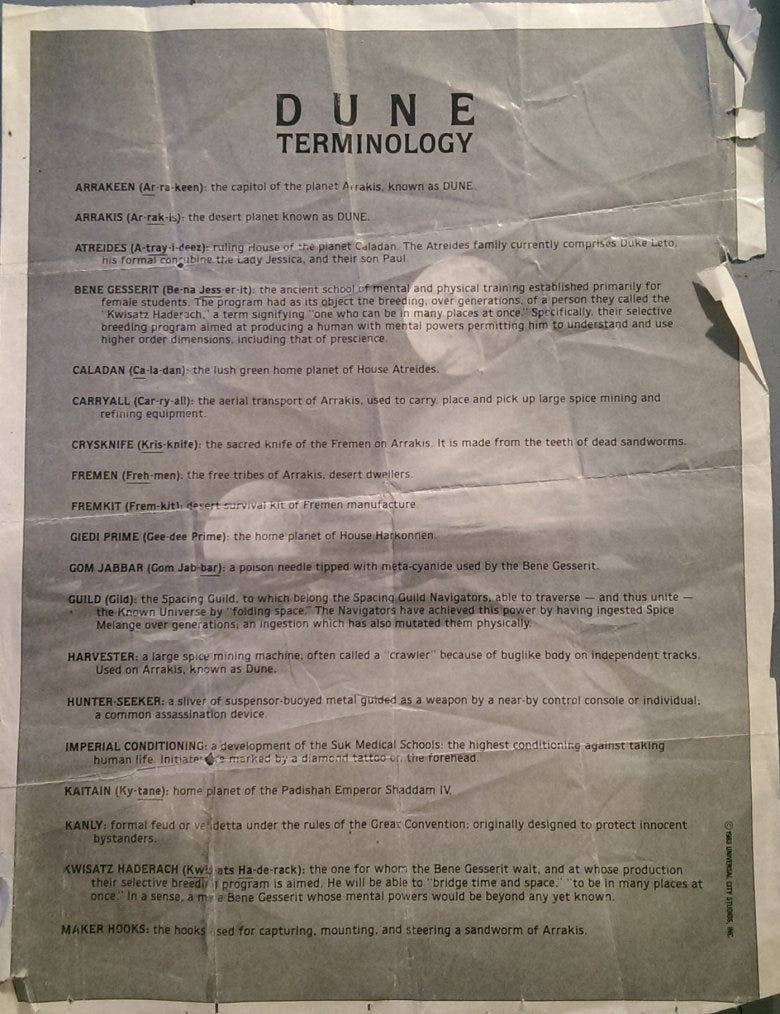

However, the allure of David Lynch, then known for Elephant Man and Eraserhead, drew Hodgman to the 1984 film adaptation. Despite his reservations, the cinematic Dune became a formative, if perplexing, experience. Entering the cinema, moviegoers were handed a glossary of terms, a move Hodgman humorously interpreted as the producers “giv[ing] up” before the film even began. This glossary, intended to demystify the complex Dune lexicon, instead signaled to a young Hodgman and his friend the potential for cinematic failure.

First page of the glossary handed out to moviegoers for the 1984 Dune movie, highlighting the film's attempt to introduce complex terminology to a general audience.

First page of the glossary handed out to moviegoers for the 1984 Dune movie, highlighting the film's attempt to introduce complex terminology to a general audience.

Adding to the surreal experience, a teenage girl and her mother, both avid Dune novel fans, sat next to Hodgman. This unexpected encounter with female Dune enthusiasts challenged Hodgman’s then-limited worldview and preconceived notions about the book’s appeal. The daughter’s favorite character, surprisingly, was the sandworms, a sentiment Hodgman found both “out there” and endearing. This personal anecdote underscores how Dune, despite its perceived niche appeal, can resonate deeply with diverse audiences.

Lynch’s Dune: A Beloved Failure and Source of Enduring Fascination

Despite acknowledging the 1984 Dune film’s shortcomings – particularly the “dumb” looking sandworms and the rushed, exposition-heavy narrative – John Hodgman professes a deep and immediate love for it. He recognizes that “it’s okay that it’s not good,” appreciating it for its ambitious failures and unique Lynchian aesthetic. Hodgman points to the studio-imposed glossary as evidence of a lack of support for Lynch’s vision, suggesting a compromised production that struggled to translate the “unfilmable” novel.

Hodgman praises the film’s “set design, the costume design, the cinematography, the visuals,” recognizing their unusual and strangely beautiful quality within the science fiction genre. He highlights the film’s successful depiction of Dune‘s alien cultural stew, where names like Stilgar and Duncan Idaho feel deliberately anachronistic, emphasizing the far-future setting. Lynch’s Dune, in Hodgman’s view, successfully captured this sense of otherworldliness, even if the narrative coherence suffered.

Specific Lynchian touches are celebrated, such as Giedi Prime’s “steampunk Borg cube full of people in bondage and discipline leather” and Brad Dourif’s Piter De Vries reciting his Sapho juice litany. These additions, not present in the novel, contribute to the film’s unique and memorable, albeit flawed, identity. Hodgman argues that while the film is “not good” in a conventional sense, it is profoundly lovable and fascinating, a testament to Lynch’s distinctive directorial voice overpowering the source material’s inherent challenges.

Peter Berg’s “Guy’s Movie” Dune and the Unfilmable Debate

Years later, a chance encounter with director Peter Berg on a flight offered John Hodgman a glimpse into another potential Dune adaptation. Berg, then known for Friday Night Lights, revealed his plans for a Dune film, envisioning it as a “classic hero’s journey” focused on “adventure and warfare” with “a little bit less of the psychosexual stuff.” This contrasted sharply with Lynch’s approach and highlighted the diverse interpretations Dune could inspire.

Hodgman recounts Berg’s confident, almost oblivious, demeanor regarding the existence of previous Dune adaptations, underscoring the pervasive challenge of adapting such a complex and previously filmed work. Berg’s spreadsheet analysis of top-grossing movies, all featuring “chosen one narratives,” further illustrated his commercial, action-oriented vision for Dune, a stark departure from Lynch’s more esoteric and visually driven approach.

This encounter solidified Hodgman’s belief in Dune‘s inherent unfilmability, at least in a traditionally satisfying cinematic sense. He uses Zack Snyder’s faithful but “unnecessary” Watchmen adaptation as a parallel, suggesting that some works are best left in their original medium. While acknowledging the thematic richness that can be mined from Dune, as demonstrated by the Watchmen TV series, Hodgman questions the necessity of a purely literal cinematic translation.

The Enduring Appeal of Dune and John Hodgman’s Nerdy Affinity

Throughout his reflection on Dune, John Hodgman’s personal connection to the material shines through. He identifies with the “third-stage Guild Navigator,” the bizarre, isolated character in Lynch’s film, seeing a reflection of his own nerdy inclinations. This self-deprecating humor and embrace of “nerd culture” are hallmarks of Hodgman’s public persona and contribute to his relatable and engaging commentary.

John Hodgman, author and humorist, alongside Kyle MacLachlan as Paul Atreides in David Lynch's 1984 Dune, representing the intersection of Hodgman's interests in Dune and cinematic adaptations.

John Hodgman, author and humorist, alongside Kyle MacLachlan as Paul Atreides in David Lynch's 1984 Dune, representing the intersection of Hodgman's interests in Dune and cinematic adaptations.

Hodgman’s journey with Dune is not just a critical analysis of a science fiction property; it’s a personal exploration of fandom, cinematic interpretation, and the enduring power of stories that resonate across generations. His humorous anecdotes, insightful observations, and genuine affection for even the flawed 1984 adaptation, offer a compelling perspective on why Dune continues to captivate and inspire diverse audiences, including self-proclaimed nerds like John Hodgman. His perspective invites readers and viewers to consider not just the quality of adaptation, but the personal and cultural significance of Dune itself.