The recent “Sargent and Fashion” exhibition at Tate Britain in London offers a compelling look into the world of John Singer Sargent, challenging viewers to consider more than just the technical brilliance of this celebrated artist. Walking through the galleries filled with Sargent’s portraits, one is immediately struck by the undeniable mastery and sheer glamour emanating from each canvas. Born in Italy to North-American parents, John S. Sargent became synonymous with high-society portraiture, capturing the essence of an era defined by opulence and carefully constructed appearances. But beyond the dazzling surfaces, do these portraits offer genuine emotional depth, or are they, as some critics suggest, beautiful but ultimately soulless?

Sargent’s subjects were predominantly women, depicted in poses and attire designed to flatter and please. Unsurprisingly, his clientele consisted of the wealthy elite – the nouveau riche and aristocracy who could afford his sought-after brush. Operating from his fashionable Tite Street studio in Chelsea, in the same circles as Oscar Wilde, John S. Sargent immersed himself in a world of privilege and presentation.

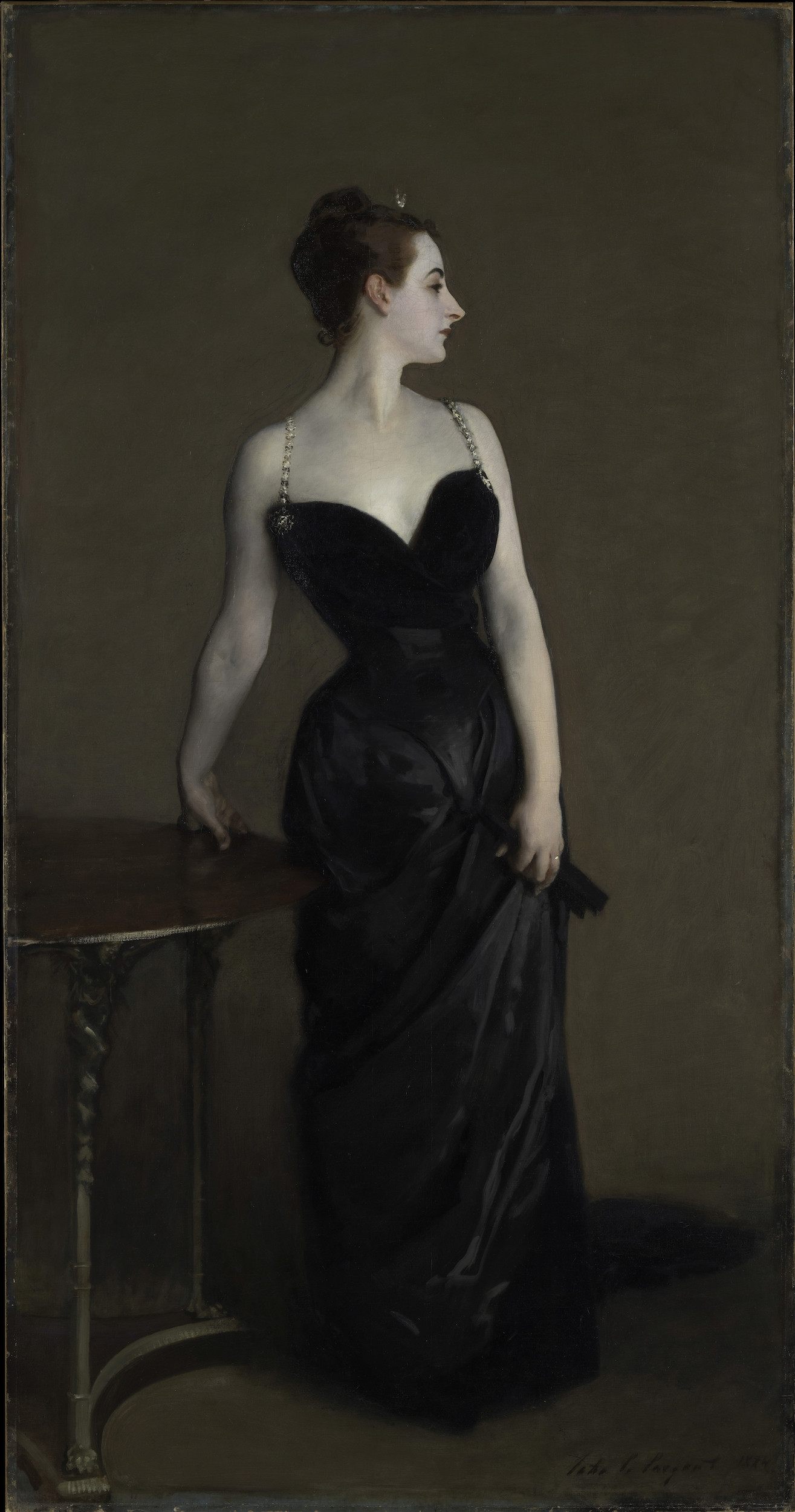

John Singer Sargent, “Madame X” (1883–84), oil paint on canvas; The Metropolitan Museum of Art

John Singer Sargent, “Madame X” (1883–84), oil paint on canvas; The Metropolitan Museum of Art

However, glimpses into Sargent’s less enthusiastic commissions reveal a different side to his artistic persona. Recalling a visit to Sheffield and encountering a Sargent portrait in the Weston Park Museum, the stark contrast becomes apparent. This particular painting depicted the daughters of a local industrialist, a commission Sargent undertook with evident disdain. His infamous 1884 letter expressing contempt for painting “three ugly young women of Sheffield, dingy hole” exposes a potential snobbery and a clear preference for his aristocratic subjects. This raises the question: did John S. Sargent’s personal biases influence the emotional depth, or lack thereof, in his portraits? Were the “Lady Mucks” truly more aesthetically pleasing in his eyes, or was it their social standing that captivated his artistic interest?

John Singer Sargent, “Lady Helen Vincent, Viscountess d’Abernon” (1904), oil paint on canvas; Collection of the Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama

John Singer Sargent, “Lady Helen Vincent, Viscountess d’Abernon” (1904), oil paint on canvas; Collection of the Birmingham Museum of Art, Alabama

As a sought-after portraitist, John S. Sargent skillfully manipulated several key elements to construct his compelling images. The exhibition “Sargent and Fashion” highlights these preoccupations: firstly, the sitter’s self-presentation within the canvas frame; secondly, their pose – whether reclining gracefully or standing rigidly; and thirdly, the crucial role of clothing. Sargent masterfully employed opulent fabrics to drape and adorn his subjects. The exhibition smartly displays original garments alongside their painted counterparts, inviting a direct comparison between reality and artistic interpretation. These carefully arranged fabrics also served practical purposes, such as subtly concealing pregnancies, a common practice among his clientele. Ultimately, the face remained paramount, capturing the sitter’s desire to be seen as eternally beautiful and captivating.

Installation view of Sargent and Fashion at Tate Britain picturing La Carmencita (c. 1890) and her costume (c. 1890)

Installation view of Sargent and Fashion at Tate Britain picturing La Carmencita (c. 1890) and her costume (c. 1890)

However, even within Sargent’s technically brilliant oeuvre, weaknesses emerge. A recurring critique centers on his depiction of hands. Often described as “porcine,” “stubby,” or disproportionately long, Sargent’s hands sometimes appear awkwardly rendered, lacking proper articulation. Whether this was due to negligence, inability, or simply lack of interest remains debatable. A close examination of “Madame X” reveals a particularly jarring example: the right hand is abruptly and unconvincingly terminated, a “hideous butchery” in the words of one critic. This same awkwardness is observed in the hands of one of the “ugly young women” from Sheffield, prompting a cynical interpretation that Sargent’s perceived disdain for his subject matter might have manifested even in his technical execution.

John Singer Sargent, “Portrait of Miss Elsie Palmer (A Lady in White)” (1889–90), oil paint on canvas; Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center

John Singer Sargent, “Portrait of Miss Elsie Palmer (A Lady in White)” (1889–90), oil paint on canvas; Colorado Springs Fine Arts Center

John Singer Sargent, “Mrs. Hugh Hammersley” (1892), oil paint on canvas; The Metropolitan Museum of Art

John Singer Sargent, “Mrs. Hugh Hammersley” (1892), oil paint on canvas; The Metropolitan Museum of Art

John Singer Sargent, “Mrs. Carl Meyer and her Children” (1896), oil paint on canvas; Tate

John Singer Sargent, “Mrs. Carl Meyer and her Children” (1896), oil paint on canvas; Tate

John Singer Sargent, “Portrait of Ena Wertheimer: A Vele Gonfie” (1904), oil paint on canvas; Tate

John Singer Sargent, “Portrait of Ena Wertheimer: A Vele Gonfie” (1904), oil paint on canvas; Tate

The “Sargent and Fashion” exhibition at Tate Britain, running until July 7th, provides a valuable opportunity to delve deeper into the complexities of John S. Sargent’s work. Curated by James Finch and Chiedza Mhondoro, the exhibition encourages viewers to look beyond the superficial glamour and technical prowess, and to consider the social context, potential biases, and artistic choices that shaped the portraits of this celebrated, yet critically debated, artist.