Episode 70 – Originally aired April 9, 2006

Written by Terence Winter

Directed by Steve Buscemi

After navigating some turbulent and philosophical episodes, “Mr. and Mrs. John Sacrimoni Request” brings us back to the grounded, yet still complex, world of The Sopranos. This episode, directed by Steve Buscemi, offers a relatively straightforward narrative, making it an accessible entry point for those interested in exploring the series, particularly the character of John Sacrimoni. While seemingly easygoing, the episode subtly delves into the pervasive theme of fantasy versus reality, a dichotomy that shapes the experiences of Tony Soprano, Allegra Sacrimoni, and Vito Spatafore in distinct yet interconnected ways. This analysis will explore how director Steve Buscemi masterfully contrasts these two concepts across the episode’s storylines, revealing deeper layers within this seemingly simple hour of television.

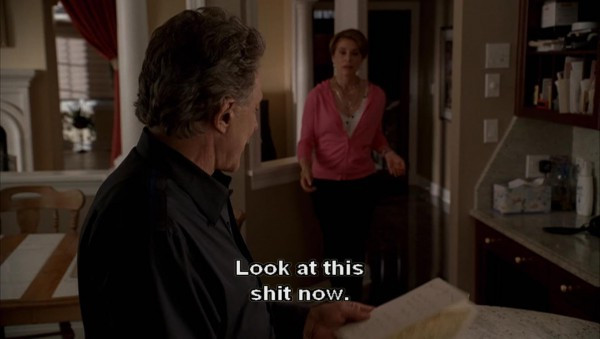

Tony Soprano returns home and to his business, but finds himself treated with kid gloves. Carmela’s overprotective demeanor and Dante Greco’s almost patronizing offer to manage Tony’s medication schedule underscore a palpable sense of vulnerability. While The Sopranos isn’t always subtle in its thematic delivery, here, the point of Tony’s weakened state is intentionally emphasized. However, the show also employs subtle visual cues. When Tony arrives at the Satriale’s backroom, the camera consistently frames a bottle of antibiotics in the shot, anchoring the scene to his ongoing recovery. This visual motif, easily missed, is brought to the forefront when Christopher Moltisanti directly mentions it:

[ Bottle1](Antibiotics bottle visually present in The Sopranos scene, emphasizing Tony Soprano’s convalescence.)

Bottle1](Antibiotics bottle visually present in The Sopranos scene, emphasizing Tony Soprano’s convalescence.)

[ Bottle2](Antibiotics bottle subtly placed in the frame during a scene with Tony Soprano, highlighting his recovery journey.)

Bottle2](Antibiotics bottle subtly placed in the frame during a scene with Tony Soprano, highlighting his recovery journey.)

[ Bottle3](Close-up view of antibiotics bottle in The Sopranos, symbolizing Tony Soprano’s ongoing healing process.)

Bottle3](Close-up view of antibiotics bottle in The Sopranos, symbolizing Tony Soprano’s ongoing healing process.)

“Antibiotics,” Christopher observes, drawing a parallel to his own health issues. Tony, a survivor of a near-fatal event, expresses a common sentiment of transformation. In therapy with Dr. Melfi, he proclaims, “Each day is a gift. And that’s how it’s gonna stay.” Tony attempts to impose a fairytale narrative on his life, envisioning a “happily ever after” where gratitude and appreciation are daily realities. However, the show, and life itself, suggests this idealized state is unsustainable.

Tony’s aspiration for a fairytale life clashes with the mundane and often harsh realities of his world. While he seeks to imbue each day with special meaning, life, as The Sopranos often portrays, is often just “the same ol’ shit.” However, moments of genuine joy and significance do punctuate life’s routine, such as weddings, which are often steeped in fairytale expectations.

The Sacrimoni family, headed by John Sacrimoni, endeavors to create a special wedding for Allegra despite the constraints of John’s imprisonment. John Sacrimoni assures his family that their celebration will be meaningful despite the “roadblocks and persecution.” The scene in the prison visiting room highlights the family dynamics, even incorporating humor with the younger daughter’s unexpected outburst about food obsessions. This quickly cuts to a familiar food market scene, complete with the grinning pig, a recurring visual motif in The Sopranos, adding a touch of dark humor and irony.

All brides dream of a perfect wedding day, and Allegra Sacrimoni is no different. For a time, her wish seems to materialize. The wedding reception is lavish, filled with the expected elements of music, dancing, fine food, and laughter. However, the intrusion of mob reality is inevitable. During the reception, John Sacrimoni orchestrates a significant event – he persuades Tony to order the hit on Rusty Millio. Rusty’s earlier reluctance to attend the wedding is humorously depicted:

[ mayor of Munchkinland](Rusty Millio, labeled “mayor of Munchkinland,” looking displeased upon receiving wedding invitation, foreshadowing his fate.)

mayor of Munchkinland](Rusty Millio, labeled “mayor of Munchkinland,” looking displeased upon receiving wedding invitation, foreshadowing his fate.)

The wedding becomes a pivotal point in Rusty’s life, albeit tragically. Tony’s agreement to eliminate Rusty at John Sacrimoni’s urging gives the episode title a dual meaning: it’s not just a request for attendance at the wedding, but a deadly “request” for a hit.

Allegra’s fairytale wedding unravels when U.S. Marshals arrive to escort John Sacrimoni back to prison. The Marshals’ SUV blocking Allegra’s limousine becomes a stark and literal representation of the “roadblocks” John Sacrimoni had dismissed earlier. Ginny Sacrimoni’s fainting spell in the ensuing chaos, with her legs comically sticking out, evokes a dark comedic image reminiscent of the Wicked Witch of the East in The Wizard of Oz.

While Ginny is no villain, the visual echoes the fairytale deconstruction theme. Moments later, after a tearful John Sacrimoni is taken away, Paulie Walnuts and Phil Leotardo discuss his emotional display.

Paulie: “His fuckin’ coach turned into a pumpkin, hehe.”

Phil: “But even Cinderella didn’t cry.”

This exchange explicitly links John Sacrimoni‘s predicament to fairytale tropes. In the hyper-masculine mob world, crying is weakness, and Phil questions John Sacrimoni‘s strength (“stugots”). Tony, however, shows empathy, perhaps recalling his own arrest in front of Meadow in Season 2:

[ Funhouse arrest](Tony Soprano’s past arrest in front of Meadow, mirroring John Sacrimoni’s public removal and adding depth to Tony’s empathy.)

Funhouse arrest](Tony Soprano’s past arrest in front of Meadow, mirroring John Sacrimoni’s public removal and adding depth to Tony’s empathy.)

Weddings often strive for a “happily ever after” ideal, a storybook romance. However, The Sopranos consistently shows the fragility of such fantasies. Even if a wedding captures a fairytale essence, marriages, like life, rarely sustain it. Vito Spatafore’s disconsolate demeanor throughout the reception highlights this. The newlyweds’ joy seems to amplify the emptiness of his own fabricated marital life. A subtle glance Vito gives to the sharply dressed Finnerty hints at the suppressed truth of his homosexuality. His discomfort culminates in him abruptly pulling Marie and their children away from the reception, even before dinner is finished.

The Sopranos frequently suggests that individuals are architects of their own unhappiness. Tony articulates this in a conversation with Carmela, stating that people create their own luck. This statement is framed by scenes that illustrate Tony’s point. First, the strained interaction between Vito and Marie, where Vito fabricates a late-night outing, exemplifies his self-imprisonment within a dishonest marriage due to his closeted sexuality. Immediately following this, the scene shifts to John Sacrimoni in actual imprisonment. John Sacrimoni, intelligent and capable, chose a life of crime, leading to his current confinement.

Vito’s prison is not physical like John Sacrimoni‘s, but equally confining. He lives a “Imitation of Life,” aptly named after the Douglas Sirk film Marie watches as Vito departs. Sirk, a German émigré, used melodramas to critique the constricted societal norms of 1950s America. Imitation of Life and All That Heaven Allows challenged the idealized American dream prevalent in media like Leave it to Beaver. Todd Haynes’ 2002 film Far From Heaven mirrored Sirk’s style, focusing on contemporary societal constraints, particularly homophobia, rather than the racial and class issues Sirk often explored.

The “gay mobster” storyline was controversial among some Sopranos viewers. Some found Vito’s leather bar sighting sensationalized or unbelievable. Others questioned Joe Gannascoli’s portrayal or simply disliked the narrative direction. While some criticisms may stem from homophobia, prevalent in 2006, it’s crucial to understand the storyline’s cultural context. In 2006, issues of gay rights were at the forefront of national debate, with President Bush advocating for the Federal Marriage Amendment and prominent figures like Ted Haggard and Mark Foley facing scandals related to homosexuality. The Sopranos Season 6, in many ways, aimed to reflect contemporary American culture and politics, and Vito’s storyline is integral to this aim.

While the Mafia is a niche subculture, The Sopranos consistently presents it as influenced by broader American societal norms. Vito’s predicament is shaped by both mob customs and American societal prejudices. Dr. Keith Mitchell, in his essay “Until the Fat Man Sings: Body Image, Masculinity and Sexuality in The Sopranos,” draws a parallel to the military’s “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy:

The jig is up for Vito, and he knows it…He knows the price of being queer and in the mob. The parallel between Vito’s situation as a closet gay man in the mob and the question of gays in the military is relevant here. Before his outing, Vito existed under a self-imposed “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” policy.

The mob, with its rigid hierarchy and “soldier” mentality, mirrors the U.S. military in some ways. Just as “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell” constrained gay service members, Vito’s survival in the mob depended on secrecy.

Vito, facing potential death, flees. He kisses his sleeping wife, grabs his gun, and escapes to a motel. The Browns’ 1959 song “The Three Bells” plays again, this time the verse about Jimmy’s wedding. Chase uses the song to subtly critique a simplistic, black-and-white worldview. Vito must flee because his colleagues are trapped in outdated, 1950s morality. The song’s idealized world is a fantasy, but Chase’s mobsters, and many Americans, yearn for this perceived “Golden Age,” blind to the complexities of human life and love. Their vision is a “feel-good fairytale”:

The Three Bells (2nd Verse)

There’s a village hidden deep in the valley

Beneath the mountains high above

And there, twenty years thereafter

Jimmy was to meet his love.

All the chapel bells were ringing,

Was a great day in his life

Cause the songs that they were singing

Were for Jimmy and his wife.

Then the little congregation

Prayed for guidance from above

“Lead us not into temptation,

Bless oh Lord this celebration

May their lives be filled with love.”

The next episode will place Vito in Dartford, a location echoing this idyllic “village hidden deep in the valley,” where he will indeed “meet his love”—Jim “Johnny Cakes” Witowski.

A humorous interlude occurs when Perry Annuziata drives Tony. Tony, noticing Perry’s physique, attempts to assert his own masculinity by recounting a weightlifting anecdote.

Tony: “There was a time when I could bench over 300 pounds.”

Perry: (unimpressed silence)

Tony: “With a major head cold one time, I did it.”

Perry: (still no response)

Tony: “If you cough with weights like that over your head, you could crush your neck.”

Tony’s attempts to impress Perry with strength and bravery fall flat. Masculinity anxieties permeate the episode. Phil Leotardo questions John Sacrimoni‘s toughness after his tears. Vito’s tough-guy persona is threatened by his outing. Tony feels emasculated by his post-surgery weakness. Dr. Melfi advises Tony to project strength, which he does by provoking and beating Perry at Satriale’s. This act, reminiscent of prison yard dominance displays, is a performance of regained power. However, the victory is fleeting, as Tony immediately vomits, highlighting the superficiality of his display.

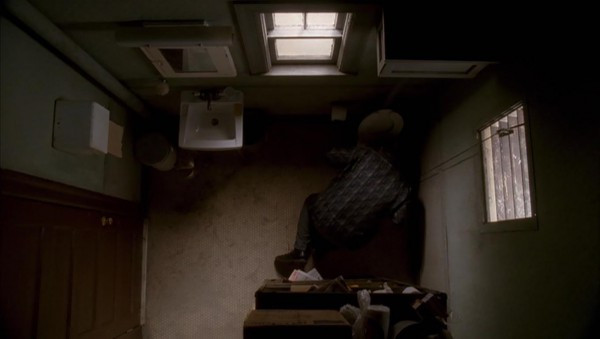

With Perry’s beating, Tony takes a step back into “the fuckin’ regularness” of his life. The Students’ 1959 doo-wop song “Every Day of the Week” plays, its lyrics emphasizing the mundane cycle of days. Tony’s earlier assertion of “each day is a gift” is juxtaposed with the reality of everyday routine. Life in Sopranos world, and perhaps life in general, is not a fairytale. Some days are ordinary, and some, like Tony’s post-fight moment, end with one’s head in a toilet.

[ Mr. and Mrs John Sacrimoni Request – toilet](Tony Soprano vomiting into a toilet, a stark contrast to the fairytale wedding and a return to harsh reality.)

Mr. and Mrs John Sacrimoni Request – toilet](Tony Soprano vomiting into a toilet, a stark contrast to the fairytale wedding and a return to harsh reality.)

The episode’s use of three 1959 artworks—Imitation of Life, “The Three Bells,” and “Every Day of the Week”—is significant. 1959 represented the end of an era, preceding the cultural shifts of the 1960s. The election of John F. Kennedy, Bob Dylan’s emergence, and the artistic revolution of the 60s quickly dated these 1959 works. Art became experimental and reflective of social change.

The 1960s brought progressive social movements: Civil Rights, the Great Society, and evolving social and sexual norms. However, backlash and concerns about governmental overreach led to a rightward swing. Regarding gay rights, however, progress has been more consistent, especially in recent decades. The Federal Marriage Amendment failed shortly after this episode aired. “Don’t ask, don’t tell” was repealed in 2011. Ted Haggard later acknowledged bisexuality. Mark Foley lived openly with his partner. The Defense of Marriage Act was weakened in 2013, and same-sex marriage was legalized nationwide in 2015. Vito’s storyline, though seemingly a digression to some, reflected a significant cultural issue of its time and may have even contributed to evolving attitudes toward homosexuality.

Beyond gay rights, the episode subtly references the War on Terror. Wedding guests pass through metal detectors, and Tony mentions Osama Bin Laden. The reappearance of Ahmed and Muhammad at the Bada Bing, with Chris’s joke about “40 thieves” and their request for semi-automatic weapons, hints at potential terrorism concerns. Despite FBI warnings, Christopher remains oblivious. While viewers might have anticipated this terrorism storyline to develop further, Chase instead focused on the “gay mobster” narrative, showcasing his penchant for subverting expectations.

Humor is prevalent throughout the episode:

- Christopher’s Allegra/antihistamine confusion.

- Christopher’s Godfather plot confusion.

- Carmela treating Tony like a child upon his return home.

- AJ’s date’s contradictory health concerns about fish and cigarettes.

- John Sacrimoni’s father’s dietary advice.

- AJ’s disbelief at the concept of event planning as a career.

ADDITIONAL POINTS:

- Christopher’s “Don’t leave home without it” line when giving stolen credit card numbers to the Muslim men ironically highlights their outsider status. The series often links criminal activities with “American” named entities.

- Corrado’s feigned dementia earlier in the series now becomes a genuine possibility for avoiding trial, adding a layer of dark irony.

- Corrado mentions taking Coumadin, a detail aligning with his mini-stroke history.

- Petey ‘Bissell’, a minor character since Season 4, is noted by nickname, fittingly named after a floor cleaner as he is seen sweeping Satriale’s.

- Mythological elements: Trees, wind, and bells appear in the wedding sequence, echoing the previous episode and gaining symbolic weight throughout the season.

- Vince Curatola praised Steve Buscemi’s direction, particularly the scene where John Sacrimoni returns to his cell in silence, emphasizing the character’s defeated state.

[ Sac – prison](John Sacrimoni in prison jumpsuit, a picture of defeat and the stark reality of his choices.)

Sac – prison](John Sacrimoni in prison jumpsuit, a picture of defeat and the stark reality of his choices.)

Follow @SopranosAutopsy

Facebook.com/RonBernard

Instagram sopranos.autopsy

Email: [email protected]

If you’d like to help support the site, please visit my Venmo or PayPal

© 2022 Ron Bernard

Share this:

- Click to share on Reddit (Opens in new window)

- Click to share on WhatsApp (Opens in new window)