King John of England from an early 14th-century illumination

King John of England from an early 14th-century illumination

King John of England as depicted in a 14th-century manuscript, capturing a regal yet perhaps troubled persona.

John, often branded with the unflattering byname “Lackland,” reigned as King of England from 1199 to 1216, a period marked by significant conflict and lasting repercussions for the English monarchy and legal system. His rule was characterized by military failures, most notably the loss of Normandy and vast Angevin territories in France, and domestic turmoil culminating in the signing of Magna Carta. While history often paints him as a villainous king, a closer examination of his life and reign reveals a more complex figure navigating the turbulent political landscape of the late 12th and early 13th centuries.

Early Life and the Shadow of Rivalry

Born around 1166, John was the youngest son of King Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. His moniker “Lackland” originated from his father’s initial inability to provide him with substantial land holdings, unlike his elder brothers. Despite being the favored son of Henry II, this lack of land was a constant source of tension and ambition in John’s early life. Henry II attempted to secure lands for John through marriage, proposing an alliance with the daughter of Humbert III of Maurienne. However, this plan was thwarted by rebellions from John’s older brothers, highlighting the inherent rivalries within the Plantagenet dynasty.

Despite these setbacks, John received various provisions in England and was appointed Lord of Ireland in 1177. His first visit to Ireland, however, between April and late 1185, was marred by youthful indiscretions and political missteps. These early experiences contributed to a growing reputation for recklessness and irresponsibility, traits that would later be amplified during his reign as king. The favoritism shown to John by Henry II further fueled tensions within the family, eventually contributing to the rebellion of his eldest surviving brother, Richard I (the Lionheart), in 1189. Intriguingly, John initially sided with Richard against their father, a decision driven by complex family dynamics and political opportunism.

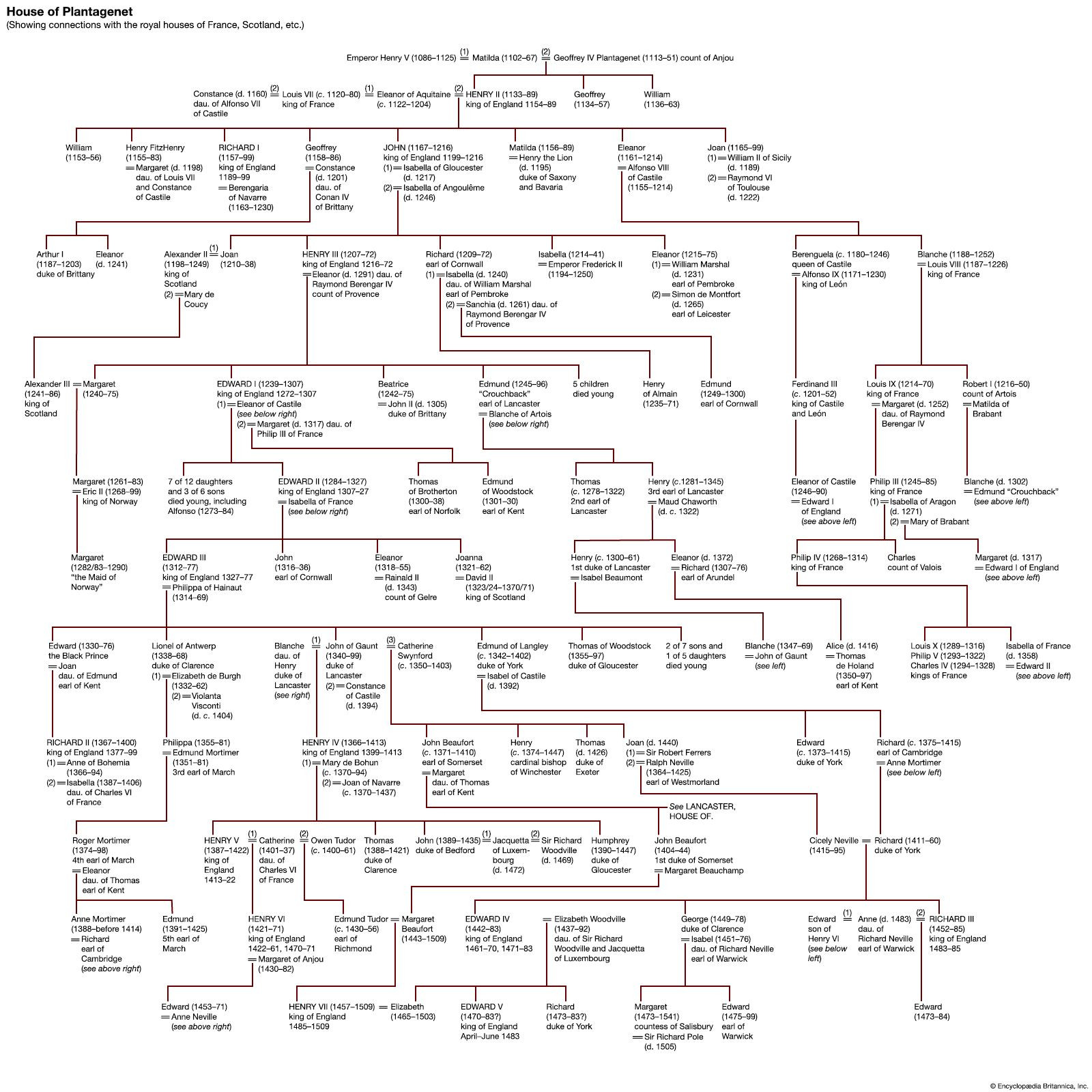

House of Plantagenet lineage illustration

House of Plantagenet lineage illustration

The House of Plantagenet family tree, showcasing King John’s place within this powerful medieval dynasty and his relationships with key figures like Henry II and Richard I.

When Richard I ascended the throne in July 1189, John’s fortunes improved considerably. He was granted the title of Count of Mortain, confirmed as Lord of Ireland, and awarded significant English lands and revenues. His marriage to Isabella, heiress to the earldom of Gloucester, further solidified his position. However, John’s ambition was far from sated. The issue of succession became paramount, with his nephew, Arthur of Brittany, posing a significant challenge. Arthur, the son of John’s deceased elder brother Geoffrey, was only three years old but represented a rival claim to the throne. When Richard recognized Arthur as his heir in 1190, John disregarded his oath of loyalty and returned to England, positioning himself as the leader of opposition against Richard’s appointed chancellor, William Longchamp.

Upon hearing of Richard’s imprisonment in Germany in 1193 during his return from the Crusade, John seized the opportunity to challenge for power. He allied with King Philip II Augustus of France and attempted to take control of England. This rebellion ultimately failed, and John was forced into a truce in April 1193. Undeterred, he continued to conspire with Philip II, plotting to divide Richard’s territories and instigate further rebellion in England. Richard’s return in 1194 led to John’s banishment and forfeiture of his lands. However, reconciliation followed in May 1195, and John regained some of his estates. Full rehabilitation and recognition as Richard’s heir came in 1196 after political maneuvering involving Arthur of Brittany and Philip II.

Ascending the Throne Amidst Succession Disputes

King John depicted hunting, a manuscript illustration from the 14th century

King John depicted hunting, a manuscript illustration from the 14th century

A 14th-century manuscript illustration depicting King John engaged in a stag hunt, offering a glimpse into the royal pastimes of the era.

The year 1199 marked a turning point. With Richard I’s death in April, the established rules of succession were still evolving. The concept of representative succession, which favored Arthur as the heir through his father Geoffrey, was not universally accepted. John, capitalizing on this ambiguity and his own political maneuvering, was invested as Duke of Normandy and crowned King of England in May 1199. Arthur, supported by Philip II of France, was initially recognized as Richard’s successor in Anjou and Maine. The political landscape remained fractured until the Treaty of Le Goulet in 1200. This treaty formally recognized John as Richard’s successor in all French territories, but at a considerable cost. John conceded financial and territorial advantages to Philip II, setting the stage for future conflicts and highlighting the precarious nature of his continental holdings.

Reign Defined by War and Continental Losses

John’s reign is largely defined by continuous warfare, particularly with France. His second marriage proved to be the catalyst for renewed conflict. His first marriage to Isabella of Gloucester was annulled in 1199 due to consanguinity. John then strategically intervened in the volatile politics of Poitou. Seeking to mediate between the Lusignan and Angoulême families, John himself married Isabella of Angoulême in August 1200. This marriage, while politically motivated, deeply offended the Lusignans, as Isabella was betrothed to Hugh IX de Lusignan.

The Lusignans’ rebellion in 1201 provided Philip II with the perfect pretext to intervene. Philip summoned John to the French court, a summons John refused to answer, effectively triggering a wider war. Initially, John achieved a notable victory at Mirebeau in August 1202, capturing Arthur of Brittany. However, this success was short-lived. Normandy fell to the French crown in 1204, a devastating loss for the English monarchy. By 1206, Anjou, Maine, and parts of Poitou were also under Philip II’s control.

These territorial losses, while culminating under John, were rooted in long-term trends dating back to the reigns of Henry II and Richard. French resources and centralized power were increasingly outstripping those of England and Normandy. Nevertheless, the losses under John were a significant blow to his prestige and dramatically altered the political landscape. Forced to spend more time in England, John’s rule took on a more personal and arguably more autocratic character. The death of Hubert Walter, the Archbishop of Canterbury and Chancellor, in 1205, further consolidated John’s personal control over government. He promoted household members to key positions and implemented ruthlessly efficient financial administration to fund his ambitions to reclaim lost territories.

King John of England, portrait from a historical text

King John of England, portrait from a historical text

A regal portrait of King John, capturing the image of a medieval ruler during a tumultuous period in English history.

John’s financial measures, including increased taxation, forest laws, taxes on Jewish communities, inquiries into feudal tenures, and exploitation of royal prerogatives, were designed to maximize royal revenue. While effective in raising funds, these policies fueled resentment among the English barons. These grievances, combined with the disastrous military campaigns, laid the groundwork for the baronial revolt that would ultimately lead to Magna Carta and solidify King John Lackland’s place in history as a controversial and ultimately transformative monarch.