If you’re visiting Harvard University, or even just browsing photos of the campus, you’re bound to see it: a bronze statue surrounded by crowds of people, all eager to capture a moment with this iconic figure. This is the John Harvard Statue, arguably the most photographed landmark on Harvard’s campus and a must-see for any visitor to Cambridge, Massachusetts. From morning until evening, a constant stream of tourists, prospective students, and even Harvard affiliates gather in Harvard Yard, cameras and phones in hand, to take selfies and group photos with this celebrated sculpture. But beyond the photo ops and the throngs of admirers, lies a story filled with fascinating myths and traditions that make the John Harvard Statue far more than just a piece of art.

The allure of the John Harvard Statue is undeniable. A quick search on Instagram for “John Harvard Statue” reveals countless posts of people from all corners of the globe posing with the bronze figure. It’s become a rite of passage for visitors, a symbol of their Harvard experience. Sandra Coh, a tourist from Lyons, France, perfectly encapsulates this sentiment: “We’re tourists,” she admits, “We visit and we take pictures.” This simple act of taking a photo embodies a desire to connect with the prestige and history of Harvard University, and the statue serves as the perfect focal point for this connection.

Visitors crowd the John Harvard statue, raising children to touch the foot.

Visitors crowd the John Harvard statue, raising children to touch the foot.

But the popularity of the John Harvard Statue isn’t solely based on its visual appeal. Adding to its mystique is the widely circulated tradition of touching the statue’s left foot. Tour guides, like Maddie Earle, encourage visitors to partake in this ritual, explaining that rubbing the bronze foot, now gleaming gold from countless touches, is said to bring good luck. This belief has amplified the statue’s draw, turning it into not just a photo opportunity, but also a source of potential fortune.

Tourists laugh, touch the feet of the statue.

Tourists laugh, touch the feet of the statue.

Among the many drawn to the statue is Tia Jackson, who made sure to touch the famed foot during her visit.

Tia Jackson touches the foot of the sculpture.

Tia Jackson touches the foot of the sculpture.

While many visitors are content with a quick photo and a touch of the lucky foot, some, like Raju Psn from Hyderabad, India, take a moment to appreciate the artistry of the John Harvard Statue. Created by renowned sculptor Daniel Chester French, who also crafted the iconic Abraham Lincoln statue for the Lincoln Memorial, the statue is rich in detail. Psn meticulously examined the skullcap, the collar tassels, and even the floral bows on the shoes. He noted the seals on the granite plinth – the seals of Harvard College and Emmanuel College, where John Harvard himself studied. For those who linger, the statue offers more than just a photo op; it’s a piece of art with historical depth.

John Harvard statue with the Yard in the background.

John Harvard statue with the Yard in the background.

Despite its revered status, the John Harvard Statue is famously known among Harvard insiders as “the statue of three lies.” This moniker, often shared by tour guides like Maddie Earle, unveils a layer of fascinating inaccuracies surrounding the monument. These “lies” don’t diminish the statue’s importance, but rather add to its intriguing narrative.

The first “lie” is perhaps the most surprising: the statue isn’t actually a likeness of John Harvard. In 1764, a fire tragically destroyed all known portraits of the University’s namesake. When Daniel Chester French was commissioned to create the statue in 1884, he had no authentic image to work from. Instead, he used Sherman Hoar, a handsome Harvard student from the Class of 1882, as his model. Adding to the irony, Sherman Hoar was a nephew of Leonard Hoar, Harvard’s fourth president, who was not particularly well-regarded. As Earle explained, “They didn’t want to name a House after this particular president for obvious reasons, so they decided to use his nephew as a regal-looking figure to commemorate John Harvard.” Thus, the face you see on the John Harvard Statue is not John Harvard, but a stand-in.

The second “lie” addresses John Harvard’s role in the University’s founding. While the statue’s inscription proclaims him as a “Founder,” this is also inaccurate. John Harvard was not a founder, but a significant early benefactor. He bequeathed his library and half of his estate to the fledgling college, a contribution so substantial that the institution was named in his honor. While crucial to Harvard’s early development, he wasn’t involved in its establishment, making the “Founder” title a historical overstatement.

The third “lie” concerns the founding date inscribed on the statue’s plinth: 1638. Harvard College was actually founded in 1636. The discrepancy of two years is a minor, yet persistent, inaccuracy that adds to the statue’s collection of misleading information.

Despite these historical fibs, or perhaps because of them, the John Harvard Statue remains a powerful symbol of Harvard University. As Raju Psn noted, even without knowing the statue’s history, he felt it embodied the University’s “lofty ideals” and found it to be “an inspirational place” that “gives us energy.”

“It’s an inspirational place. It gives us energy.”

“It’s an inspirational place. It gives us energy.”

For many, the John Harvard Statue represents more than just history or art; it’s a tangible connection to the Harvard experience. For prospective students and their families, posing with the statue is often seen as a hopeful gesture, a way to manifest future admission to this prestigious institution. Marco Mayolo, a teacher from Colombia, who visited with his family, shared this belief: “We know of the University legend that if you get a picture with the statue, you will study here in the future.” He and his wife even helped their infant son touch the foot, symbolically extending this hope to the next generation.

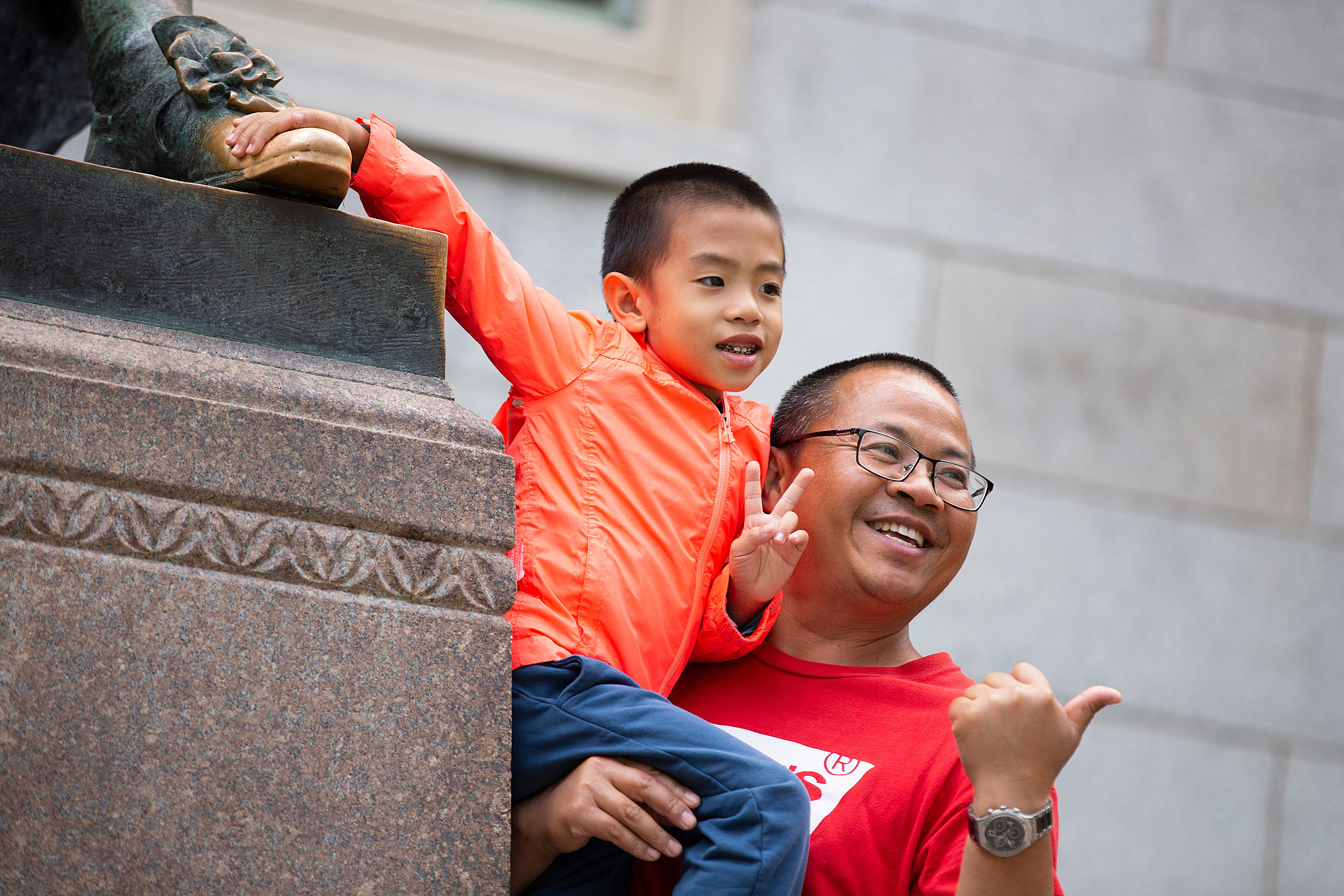

Father holds 6-year-old son who touches the statue

Father holds 6-year-old son who touches the statue

A father hoists his 7-year-old son to reach the foot of the statue.

A father hoists his 7-year-old son to reach the foot of the statue.

Families often participate in the tradition, hoping for good fortune related to Harvard.

Amid onlookers thronging statue a visitor holds up her cellphone.

Amid onlookers thronging statue a visitor holds up her cellphone.

For current Harvard students, like Sammota Mwakalobo, the John Harvard Statue takes on a different meaning. It’s a marker of their journey, a symbol of the beginning of their Harvard experience. Mwakalobo, who led campus tours, recalled taking her own photo with the statue as a newly admitted student. “It’s a thing that’s expected,” she explained. “It’s the iconic thing to do. It’s as though your experience would be lacking something if you didn’t. For me, it marked the beginning of my journey.”

Sammota Mwakalobo leads a tour group by the statue.

Sammota Mwakalobo leads a tour group by the statue.

In conclusion, the John Harvard Statue is far more than just a bronze sculpture in Harvard Yard. It’s a cultural phenomenon, a tourist magnet, and a repository of lore and legend. It embodies the prestige of Harvard University, serves as a backdrop for countless memories, and stands as a testament to the enduring power of symbols. Whether you’re drawn by the good luck tradition, the artistic details, or simply the desire to capture an iconic Harvard moment, a visit to the John Harvard Statue is an essential part of any Harvard experience.