King John Of England, often remembered for his conflicts and ultimate concession of the Magna Carta, reigned from 1199 to 1216. His rule was marked by significant losses of land in France and mounting discontent within England, culminating in the landmark charter that limited royal power. This exploration delves into the life and reign of King John, examining his early years, ascension to the throne, disastrous wars, and the legacy he left behind.

King John of England, from an early 14th-century illumination

King John of England, from an early 14th-century illumination

Early Life and Rivalry for the Crown

Born around 1166, John was the youngest son of King Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. He earned the moniker “Lackland” because, unlike his elder brothers, he was not initially granted extensive land holdings. Despite being his father’s favorite, attempts to secure lands for John through marriage to the daughter of Humbert III of Maurienne were thwarted by rebellions from his brothers. While provisions were made for him in England and he was granted lordship of Ireland in 1177, his early forays into Irish politics were marked by youthful indiscretions, damaging his reputation.

Henry II’s favoritism towards John fueled tensions with his eldest surviving son, Richard I (the Lionheart). Intriguingly, John initially sided with Richard in rebellion against their father in 1189. The reasons remain unclear, but this act highlights the complex dynamics within the Plantagenet family.

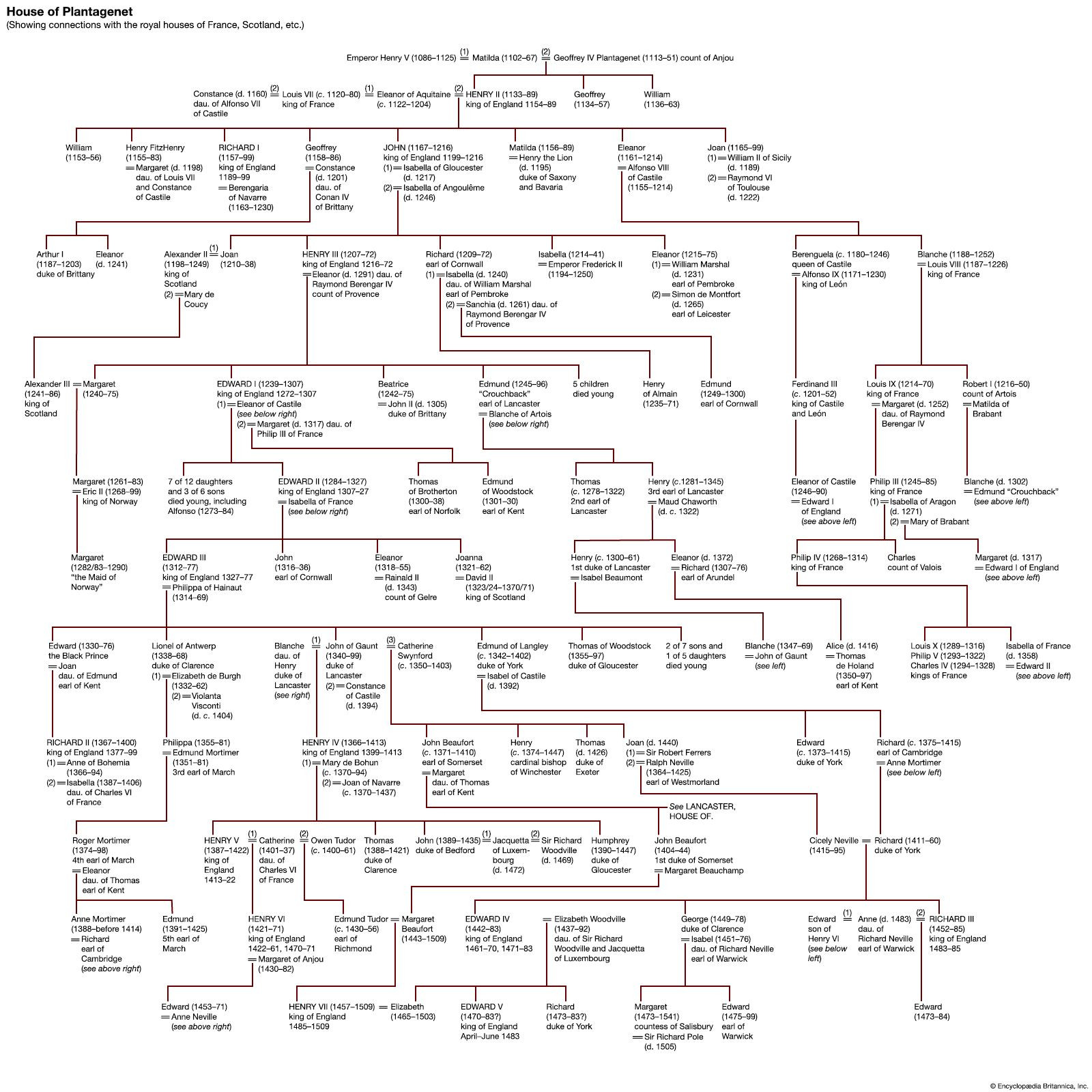

House of Plantagenet

House of Plantagenet

Upon Richard I’s ascension to the throne in July 1189, John was granted significant titles and lands, including Count of Mortain and Lord of Ireland, alongside substantial revenues in England. However, he was also compelled to pledge not to enter England during Richard’s Crusade. The issue of succession quickly became central to John’s ambitions. His nephew, Arthur of Brittany, son of his deceased brother Geoffrey, emerged as a rival claimant. When Richard declared Arthur his heir in 1190, John disregarded his oath and returned to England, positioning himself against Richard’s chancellor, William Longchamp.

News of Richard’s imprisonment in Germany in 1193 spurred John to ally with King Philip II Augustus of France, attempting to seize control of England. This rebellion failed, and John was forced into a truce in April 1193. He continued to conspire with Philip, planning to divide Richard’s territories. Upon Richard’s return in 1194, John was banished and stripped of his lands. Reconciliation followed in May 1194, and by 1195, he regained some estates, including Mortain and Ireland. Full rehabilitation came in 1196 after Arthur was surrendered to Philip II, leading Richard to finally recognize John as his heir.

John, king of England

John, king of England

King John’s Accession to the Throne

In 1199, the concept of representative succession favoring Arthur was not firmly established. Following Richard’s death in April 1199, John was invested as Duke of Normandy and crowned King of England in May. Arthur, supported by Philip II, was recognized as Richard’s heir in Anjou and Maine. The Treaty of Le Goulet a year later formally recognized John as Richard’s successor in all French territories, but at the cost of financial and territorial concessions to Philip.

The Disastrous War with France and Loss of Normandy

The resumption of war with France was ignited by King John’s second marriage. His first marriage to Isabella of Gloucester was annulled in 1199 due to consanguinity. John then intervened in Poitou and, seeking to resolve disputes between the Lusignan and Angoulême families, married Isabella of Angoulême in 1200. This politically motivated marriage, however, backfired, provoking the Lusignans into rebellion. They appealed to Philip II, who summoned King John to his court. John’s refusal led to war. A temporary victory at Mirebeau in 1202 saw Arthur of Brittany captured, but this was short-lived. Normandy fell to the French by 1204. By 1206, Anjou, Maine, and parts of Poitou were also under Philip’s control.

These territorial losses, while foreshadowed during the reigns of Henry II and Richard, were significantly exacerbated by French strength and the overstretched resources of England and Normandy. These failures deeply damaged King John’s prestige and resulted in his near-permanent residence in England. Coupled with the death of Archbishop Hubert Walter in 1205, John’s government took on a more personal and arguably autocratic character, marked by the elevation of household members to key positions. His determination to reclaim lost territories fueled ruthless financial administration, including increased taxation, forest inquiries, taxes on Jewish communities, and stringent enforcement of feudal prerogatives. These measures laid the groundwork for accusations of tyranny that would later define his reign and lead to the Magna Carta.

King John’s reign remains a pivotal period in English history, primarily due to the Magna Carta. While often viewed negatively, his rule and the events surrounding it significantly shaped the relationship between the English monarchy and its subjects, leaving a lasting impact on the development of English law and governance.