The gripping narrative of FX’s Shōgun unfolds largely through the eyes of John Blackthorne (masterfully portrayed by Cosmo Jarvis). He’s an English navigator who, in the year 1600, finds himself shipwrecked in Japan, a nation teetering on the brink of civil war. While the intricate plot of Shōgun is born from imagination, the character of John Blackthorne is not entirely fictional. He’s inspired by a real historical figure, a man whose journey to Japan was just as extraordinary.

Who Was the Real John Blackthorne? Meet William Adams

Cosmo Jarvis as John Blackthorne in FX's Shōgun

Cosmo Jarvis as John Blackthorne in FX's Shōgun

Cosmo Jarvis embodies the role of John Blackthorne, an English pilot navigating the complexities of feudal Japan in FX’s Shōgun. (Image courtesy of Disney+)

John Blackthorne, the compelling protagonist of Shōgun, draws his essence from William Adams. Adams holds the distinction of being the first Englishman to definitively reach the shores of Japan. Remarkably, he is also considered by some to be one of the few Westerners to ever attain the esteemed rank of samurai.

Just as Blackthorne forges a crucial alliance with the powerful warlord Yoshii Toranaga (played by Hiroyuki Sanada) in the dramatic series, William Adams cultivated a close and influential relationship with the historical figure who inspired Toranaga: Tokugawa Ieyasu. Ieyasu, a shrewd and ambitious warlord (learn more about Tokugawa Ieyasu, the real Toranaga), would come to rely on Adams’s expertise in trade and diplomacy after his ascent to shōgun. This trust led to significant honors for Adams, including grants of land, the prestigious title of hatamoto (a high-ranking samurai retainer), and the symbolic gift of two swords, signifying his elevated samurai status – even though he was not a warrior in the traditional sense.

The Early Life of William Adams: From Kent to the Seas

William Adams’s story begins in September 1564, in Gillingham, Kent, England. Details of his early years are scarce, but valuable insights come from Adams himself, through a letter penned in 1611 from Hirado, a Japanese port, addressed to his ‘Unknown friends and countrymen’.

This letter reveals that at the age of twelve, Adams was apprenticed to Nicholas Diggins in Limehouse, London. Here, he immersed himself in the nautical arts, mastering navigation, astronomy, and shipbuilding – skills that would prove pivotal in his extraordinary future. He remained in this apprenticeship until he was 24, a significant year in English history: 1588, the year of the Spanish Armada (discover more about the Spanish Armada).

In 1588, Adams joined the navy of Sir Francis Drake, a legendary English admiral. Records indicate Adams served aboard the Richard Duffylde, a supply vessel in the English fleet. Whether he directly participated in the naval battles against the Armada remains uncertain, but this period undoubtedly shaped his maritime experience.

Following England’s victory and the disbandment of the Queen’s fleet, Adams sought new avenues for his seafaring skills. He spent a decade working with the merchants of the Barbary Company, gaining further experience in trade and navigation. Eventually, drawn by the lure of the East, Adams turned to the Dutch fleets venturing towards Asia, a decision that would ultimately lead him to Japan.

The Dutch Route to Asia and the Voyage to Japan

The Dutch Republic, in the late 16th century, was locked in a protracted war with Spain. This conflict intensified in 1581 when King Philip II of Spain inherited the Portuguese throne. This political shift had significant economic repercussions for Dutch merchants, who had previously relied on Lisbon as their primary hub for sourcing Asian goods. Suddenly, Lisbon’s ports were closed to them, forcing them to seek direct trade routes to Asia if they wished to maintain their access to valuable Asian commodities.

This shared conflict with Spain naturally fostered a sense of camaraderie between Dutch and English sailors. In 1598, William Adams’s expertise was sought by a Dutch fleet embarking on a voyage to the East Indies. He was employed as a pilot – in essence, a master navigator – for this ambitious expedition.

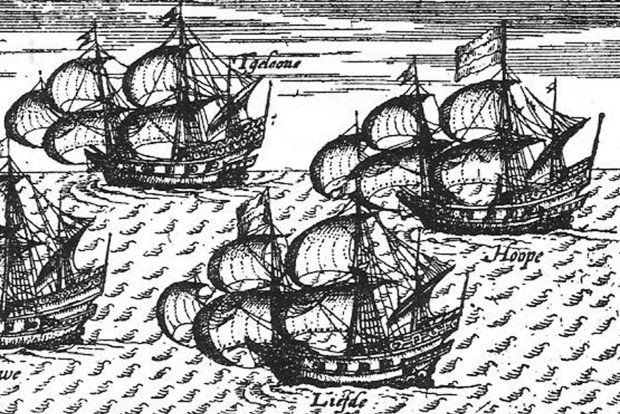

The Dutch fleet, consisting of five ships, set sail from Rotterdam in 1598. However, the arduous journey took a heavy toll. Remarkably, only one ship, the Liefde (meaning “Love” in Dutch), reached Japan in April 1600, nearly two years after their departure. The crew of the Liefde was drastically reduced, with only about twenty men surviving from an original complement of over a hundred, many weakened by malnutrition and disease. William Adams was among these resilient survivors.

The planned route was ambitious and fraught with peril: to sail through the Strait of Magellan, raid Spanish ships and settlements along the South American coast, and then trade these spoils in Asia before returning to Europe via the same route. Frederik Cryns, an expert on William Adams’s life and historical consultant for FX’s Shōgun, explained in a HistoryExtra podcast that the voyage deviated drastically from the initial plan due to unforeseen challenges.

“They had a lot of problem with first the winds, so they couldn’t proceed on schedule. They didn’t have enough food, so a lot of the sailors starved. They had diseases and they had to fight the Portuguese, then they had to fight the Spanish. And when they came into South America, they were attacked by the native peoples living there.”

Tragically, these attacks in South America claimed the life of Adams’s brother, Thomas. Cryns further detailed the disastrous fate of the five-ship fleet: “Of the five ships, one went back to Holland, one was captured by the Spanish, one was captured by the Portuguese, one was lost in a storm, and eventually there was only one ship left,” says Cryns. “That was the Liefde, which arrived in Japan in April 1600, two years after they departed.”

Dutch ships at sea

Dutch ships at sea

The Liefde, depicted here among other Dutch vessels, was the sole ship from the original five-ship fleet to successfully reach Japan, marking a pivotal moment in history. (Photo by Getty)

Upon arrival in Japan, the weary crew of the Liefde were met with suspicion by the local Japanese population and the fervent opposition of Portuguese Jesuit missionaries. Until this point, the Portuguese held a monopoly on European interactions with Japan and were determined to maintain their exclusive access. They actively attempted to portray the Dutch crew as pirates in the eyes of the Japanese authorities, a dangerous accusation that could have resulted in the crew’s execution.

However, fate intervened when news of the Liefde‘s arrival reached Tokugawa Ieyasu. Ieyasu was one of Japan’s most powerful daimyo (feudal lords) and a key figure among the five regents governing the country on behalf of the young heir, Toyotomi Hideyori. Ieyasu, a man of keen intellect and strategic vision, held a different perspective on the arrival of these unexpected Europeans.

The Limited Role of William Adams in Tokugawa Ieyasu’s Rise to Shōgun

FX’s Shōgun, mirroring James Clavell’s bestselling novel, portrays John Blackthorne as instrumental in Lord Toranaga’s ascent to becoming the dominant warlord of Japan. In the fictional narrative, Blackthorne’s unique insights and “barbarian” perspectives prove crucial to Toranaga’s triumph over his rival, Lord Ishido, culminating in the Battle of Sekigahara in October 1600. The novel even depicts Blackthorne directly intervening to save Toranaga from death or capture on multiple occasions.

However, historical accounts reveal a different reality for William Adams. During the period of Ieyasu’s power struggle with Ishido Mitsunari (Ishido’s real-life counterpart), Adams played a far less prominent role. Cryns’s biography, In the Service of the Shōgun, dedicates only two pages to the period depicted in Shōgun, highlighting Adams’s limited involvement in these events.

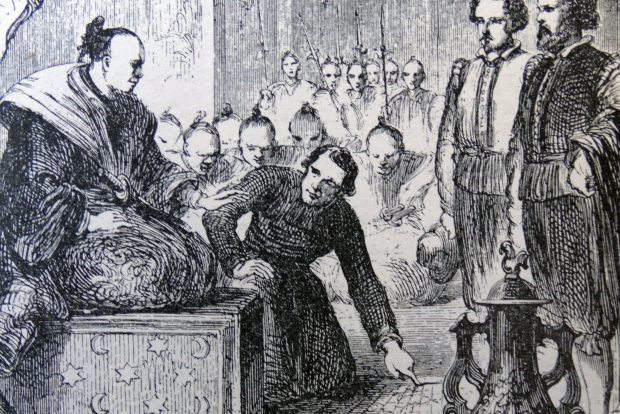

After being brought before Ieyasu in Osaka, Adams and his surviving crewmates were imprisoned and subjected to intermittent interrogations. Subsequently, Adams was released and relocated to Uraga, a harbor near Edo (present-day Tokyo), where the Liefde and the remaining crew were also moved. While denied permission to repair the Liefde and depart Japan, Adams was otherwise largely left to his own devices.

“He’s just sitting idle while Ieyasu fights his final battle against Ishida Mitsunari at Sekigahara,” Cryns clarifies. “It’s only after Ieyasu establishes his rule and everything stabilises that Adams is asked to join him.” It was after Ieyasu solidified his power that Adams’s true influence began to emerge, as he was summoned to become an advisor to Ieyasu on the wider world beyond Japan.

William Adams before Tokugawa Ieyasu

William Adams before Tokugawa Ieyasu

William Adams stands before Tokugawa Ieyasu. This encounter marked the beginning of a significant relationship, with the Englishman becoming one of the shōgun’s most trusted confidantes. (Photo by Getty)

The Real Relationship Between Adams and Ieyasu: Advisor and Confidant

While William Adams did not directly orchestrate Ieyasu’s path to becoming shōgun, their relationship became profoundly significant. Contrary to some fictional portrayals, Adams did not teach Ieyasu how to dive. However, he evolved into one of Ieyasu’s most trusted advisors, profoundly shaping Japan’s interactions with European powers.

Even after the decisive Battle of Sekigahara in 1600, Ieyasu faced ongoing domestic challenges. It wasn’t until the summer of 1615, fifteen years after Sekigahara, that he fully quelled all opposition and established himself as the undisputed ruler of Japan. Another pressing concern for Ieyasu was the Portuguese monopoly on foreign trade, particularly in valuable commodities like Chinese silks, essential for Japanese clothing, and lead, crucial for weapon manufacturing.

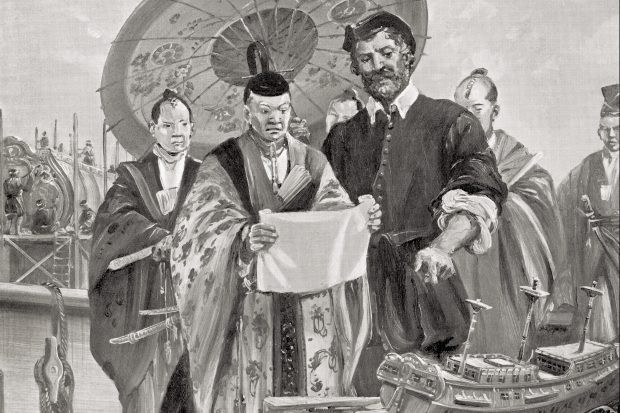

By 1603, Adams had relocated from Uraga to Edo, becoming a frequent presence in Ieyasu’s court. During one of these audiences, Ieyasu requested Adams to construct a Western-style ship. Adams, with the assistance of Japanese craftsmen, successfully fulfilled this request, introducing Western shipbuilding techniques to Japan. Impressed by Adams’s 80-tonne vessel and recognizing the strategic importance of maritime trade, Ieyasu brought Adams into his inner circle. Adams became a tutor and advisor to Ieyasu, sharing his knowledge of mathematics, geometry, astronomy, and the intricacies of global politics.

William Adams showing ship designs to Tokugawa Ieyasu

William Adams showing ship designs to Tokugawa Ieyasu

Englishman William Adams presents his ship designs to Japanese shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu, showcasing his shipbuilding expertise and further solidifying his position as a valuable advisor.

When Adams completed a second, larger ship of 120 tonnes, a delighted Ieyasu bestowed upon him significant rewards. Adams was granted an estate on the Miura peninsula and elevated to the rank of hatamoto, a direct retainer of the shōgun. This prestigious appointment came with increased income and numerous households to serve him, effectively making Adams a minor lord within Japan.

Amidst his rising influence, Adams advocated for Ieyasu to establish trade relations with Dutch and English merchants. Though forbidden from leaving Japan himself, Adams facilitated communication, persuading Ieyasu to allow two of his crewmates to return to Europe. This initiative led to the arrival of the first Dutch vessel in Japan since the Liefde in 1609. Subsequently, letters conveyed by outbound traders paved the way for the English to reach Japan in 1613. Adams, now Ieyasu’s official interpreter, played a central role in establishing an English trading factory in Japan.

Perhaps Adams’s most impactful moment came in 1611 with the arrival of the Spanish, who offered trade on the condition that Ieyasu sever ties with the Dutch. Cryns explains, “That of course Ieyasu cannot allow. It’s totally contrary to his own policy,” However, Ieyasu permitted the Spanish to trade and to send missionaries to Japan. He also granted them permission to survey Edo Bay, ostensibly as an anchorage for trading ships. Upon learning of this, Adams strongly cautioned Ieyasu against it, convinced that the survey was a precursor to a Spanish invasion.

Cryns notes that Ieyasu initially believed his army could effectively counter any invasion. “But then, Adams says, you have to be aware because they send missionaries, they will make a lot of Christians in Japan, and then together they cooperate with those Christians to overthrow your government.” This warning had a profound impact on Ieyasu.

Cryns emphasizes the significance of this dawning realization for Ieyasu: “That’s really the beginning of the suppression of the Christians in Japan. And that will culminate afterwards into the closing of Japan for all the Christians, and the Portuguese and the Dutch being transferred to Nagasaki, where they will stay on an artificial island and not allowed to come on Japanese soil.” This pivotal shift in policy, leading to the eventual isolation of Japan, was significantly influenced by Adams’s counsel to Ieyasu, underscoring his immense impact on Japan’s future diplomatic trajectory.

Miura Anjin: The Japanese Name of John Blackthorne’s Inspiration

In FX’s Shōgun and Clavell’s novel, John Blackthorne is frequently addressed as ‘Anjin’. This is ostensibly because the Japanese find his English name difficult to pronounce. ‘Anjin’ is the Japanese term for pilot or navigator, reflecting Blackthorne’s profession.

William Adams also acquired a similar Japanese name. Following the grant of his estate on the Miura peninsula, he became known as ‘Miura Anjin’, literally meaning “the pilot of Miura,” solidifying his identity within Japanese society.

The Death of William Adams and His Legacy

William Adams passed away on May 16, 1620, four years after the death of Ieyasu. He left behind a complex family legacy, with a wife, Mary Hyn, and two children in England – a son and a daughter born after his departure in 1598. He had also married a Japanese woman and is believed to have fathered two more children in Japan.

Never to Return: William Adams’s Choice to Remain in Japan

The narrative of Shōgun concludes with Toranaga suggesting that it was Blackthorne’s destiny to never leave Japan. Similarly, William Adams, his real-life inspiration, never returned to England. However, unlike a forced exile, Adams’s choice to remain in Japan was ultimately his own. In 1613, Ieyasu granted him permission to return to England permanently.

Despite this offer of freedom, Adams declined. Instead, he chose to enter the service of the British East India Company, navigating expeditions to Siam (present-day Thailand) and later, independently, to Vietnam. Cryns suggests several factors that contributed to Adams’s decision to remain in Japan:

“I think that there were a lot of aspects which kept him in Japan,” says Cryns. “In Japan he was a small lord. He had a fief allotted to him by Ieyasu. He had households serving him.” He continues, “He was a man of influence in Japan. But if he went back to England, he was just another sailor.” In Japan, William Adams had carved out a unique and influential position for himself, a position that would have been difficult, if not impossible, to replicate back in England.

Experience the epic story of Shōgun streaming on Disney+. Dive deeper into historical narratives with our curated list of the best historical movies and explore more historical TV and film to stream tonight. Stay updated on the latest historical content with our weekly guide to new history TV and radio in the UK.

Further Reading:

Frederik Cryns’s book, In the Service of the Shogun: The Real Story of William Adams, provides an in-depth exploration of the life of the real John Blackthorne and is available from Reaktion Books (released May 2024).