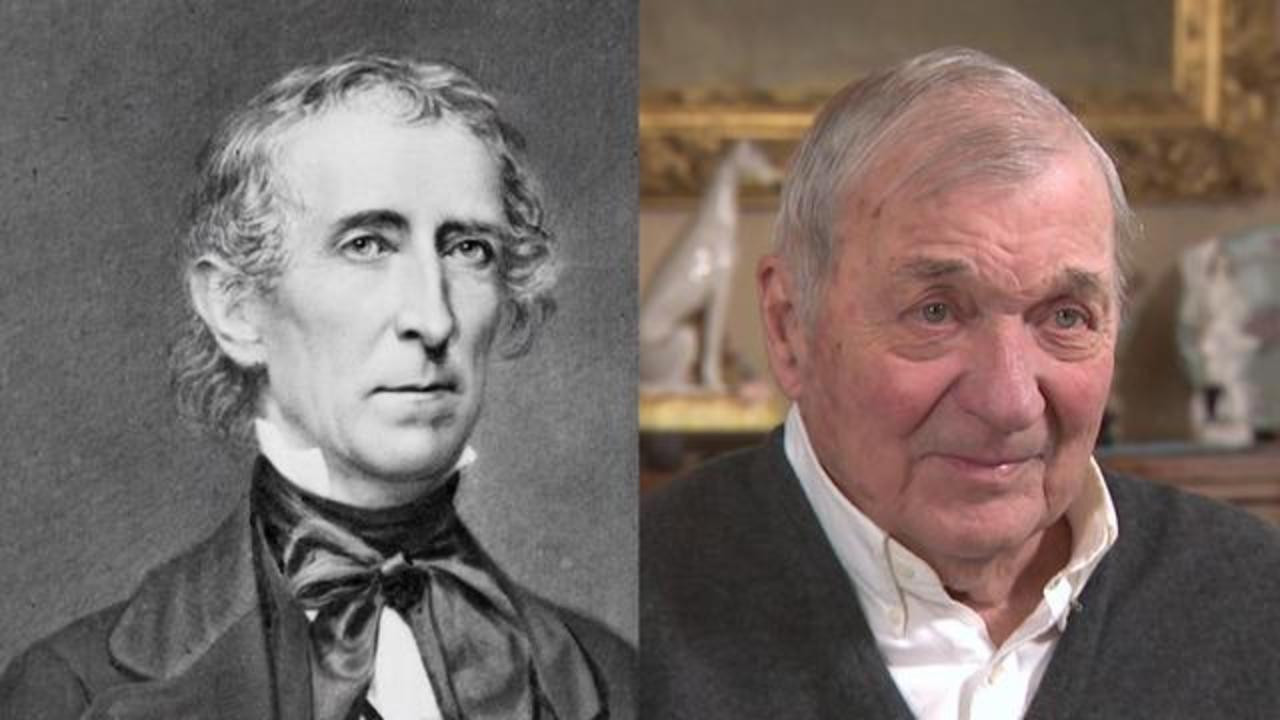

American history, while extensive and filled with pivotal moments over two centuries, is in some ways remarkably recent. It’s a history that feels surprisingly tangible when you realize that a grandson of John Tyler, the tenth President of the United States, is alive and well today. Born in 1928, Harrison Ruffin Tyler, a nonagenarian at ninety-four years old, continues to reside in Virginia, the ancestral home of the Tyler family. This incredible fact bridges the gap between our modern era and the early days of the American republic, offering a unique perspective on the passage of time and the enduring legacies of historical figures like President John Tyler.

President John Tyler (left) and his grandson Harrison Ruffin Tyler (right).

President John Tyler (left) and his grandson Harrison Ruffin Tyler (right).

President John Tyler, Harrison Ruffin Tyler’s grandfather, was born in 1790, during George Washington’s presidency. Tyler was a staunch originalist, deeply committed to the Constitution. He believed it to be the supreme law of the land, demanding unwavering adherence without compromise. This conviction solidified during his time studying law at the College of William and Mary. The 19th century was a period of immense political turmoil, dominated by the contentious issues of states’ rights and slavery. As abolitionist movements gained momentum, so did the fervent defense of slavery. Tyler firmly advocated for states’ rights, including on the issue of slavery. During his tenure as a House Representative for Virginia’s 23rd district, he opposed the Missouri Compromise of 1820. His opposition stemmed from the federal legislation dictating Missouri’s status as a slave state and Maine as a free state, arguing that states should have the autonomy to decide on the matter of slavery themselves. Despite his political stance, it’s noted that Tyler himself was a slave owner, even while expressing personal reservations about the institution.

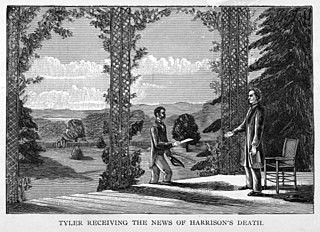

Tyler’s staunch originalist views were tested early in his vice presidency. Elected in 1840 on the Whig ticket with presidential candidate William Henry Harrison, a move intended to attract Southern voters, Tyler unexpectedly became president just a month into Harrison’s term. President Harrison’s sudden death on April 4, 1841, thrust Tyler into the presidency, but not without initial controversy. Article II, Section 1, Clause 6 of the Constitution stipulated the Vice President would assume the “Powers and Duties” of the President upon the President’s removal, death, resignation, or inability to discharge the office. Many interpreted this to mean Tyler should become “Acting President,” temporarily fulfilling the presidential role but not fully inheriting the title and office. Tyler vehemently disagreed. He asserted he was the full President and was promptly sworn in as such, claiming this decisive action was crucial for national security.

Newspaper illustration of VP Tyler receiving the news of President Harrison’s death. Tyler was not in Washington at the time (though he knew Harrison was ill) to prevent looking overly-prepared to assume the Presidency.

Newspaper illustration of VP Tyler receiving the news of President Harrison’s death. Tyler was not in Washington at the time (though he knew Harrison was ill) to prevent looking overly-prepared to assume the Presidency.

Personal tragedy struck Tyler during his presidency when his first wife, Letitia, passed away in 1842. She was the first of three presidential spouses to die while their husbands were in office. In 1844, at the age of 54, Tyler remarried to Julia Gardiner. They had seven children, including Lyon Gardiner Tyler (1853-1935). Lyon’s birth when John Tyler was 63 years old is one key factor in understanding how a grandson of the tenth president is still living today. Lyon Gardiner Tyler followed in his father’s footsteps to the College of William and Mary, later becoming its 17th president. The second remarkable element in this extended lineage is that Lyon also had a child late in life. After his first wife, Anne, died in 1921, Lyon married Sue Ruffin, who was 35 years his junior. In 1928, at the age of 75, Lyon and Sue welcomed Harrison Ruffin Tyler into the world.

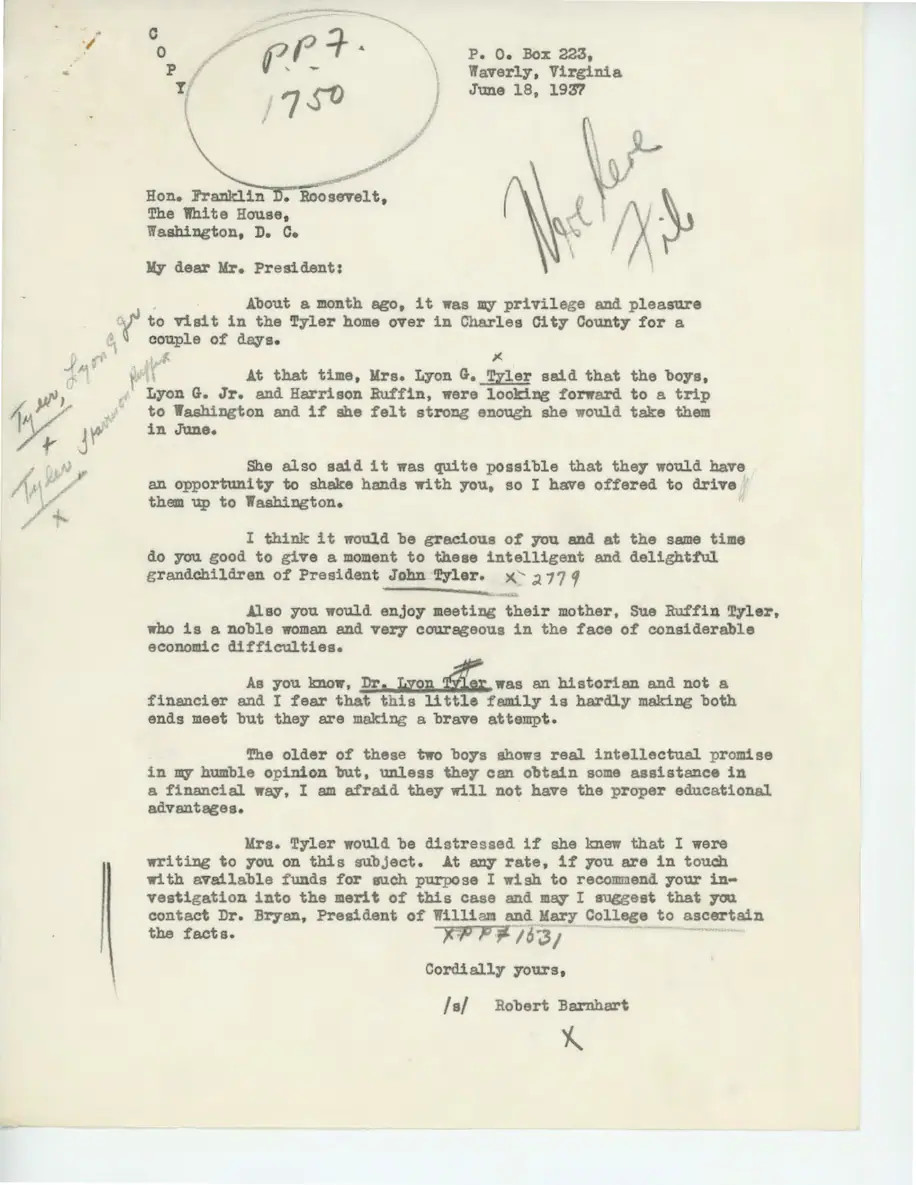

Despite his prestigious lineage, Harrison Ruffin Tyler’s early life was marked by the economic hardship of the Great Depression. He was primarily homeschooled by his mother. When it was time for college, a $5,000 check arrived to fund his education. Historians believe this financial support came from President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, who had a close relationship with Harrison’s father, Lyon. Supporting this theory is a 1937 letter from Robert Barnhart, a colleague of the late Lyon Tyler, to President Roosevelt. This letter, housed in the Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library, requests “some assistance in a financial way” for Lyon’s two sons, noting their “real intellectual promise.”

Scanned copy of the letter from Mr. Robert Barnhart to President Roosevelt on behalf of the grandchildren of 10th President John Tyler, 1937.

Scanned copy of the letter from Mr. Robert Barnhart to President Roosevelt on behalf of the grandchildren of 10th President John Tyler, 1937.

With this crucial financial assistance, Harrison Ruffin Tyler attended his grandfather’s alma mater, the College of William and Mary, earning a chemistry degree in 1949. He continued his education, obtaining a Master’s degree in Chemical Engineering from Virginia Polytechnic Institute in 1951. Harrison’s professional life included co-founding the water treatment company “ChemTreat” in Virginia in 1968. In 1975, he took on the responsibility of preserving his family history by purchasing Sherwood Forest Plantation, his grandfather John Tyler’s home for the last two decades of his life, and undertaking its restoration. Although Harrison faced health challenges later in life, including a series of strokes beginning in 2012 and the development of dementia, his legacy is secure. His son, William, now manages Sherwood Forest, which has become a historical landmark and popular tourist destination. In recognition of Harrison Ruffin Tyler’s lifelong support and significant donations of Tyler family documents, the College of William and Mary honored him in 2021 by naming the “Harrison Ruffin Tyler Department of History” in his honor.

Julia Gardiner Tyler, second wife of President Tyler. Painted by Francesco Anelli, 1840s.

Julia Gardiner Tyler, second wife of President Tyler. Painted by Francesco Anelli, 1840s.

The continued life of Harrison Ruffin Tyler serves as an astonishing reminder of the relatively short span of American history and the enduring connections to its formative eras. His existence provides a tangible link to the 19th century, to the presidency of John Tyler, and to the very foundations of the United States. It’s a remarkable piece of living history, demonstrating how the past remains vibrantly present.