John Milius. The name conjures images of surfboards, guns, and epic tales of heroism and rebellion. Stepping into his office at Warner Bros., as described in a 1997 interview, is like entering the mind of a cinematic warrior. Filled with diverse artifacts – from surfboards to military regalia, and posters of Conan the Barbarian – the most striking feature is the collection of leather-bound screenplays. These volumes represent a substantial body of work, solidifying John Milius’s place not just as a director, but as a writer of immense influence.

Born in St. Louis but raised in Southern California from the age of seven, John Milius discovered his first passion in surfing. He described it as a powerful, almost religious experience, an intensity unmatched by anything else. Nicknamed “Yeti, the abominable snowman” by his surfing companions, Milius initially aspired to a military career. However, asthma prevented him from joining the Army. Film school became his unexpected next chapter, a path he embarked on without anticipating a life beyond the pursuit of the perfect wave.

John Milius on the set of Conan the Barbarian with Arnold SchwarzeneggerJohn Milius directing Arnold Schwarzenegger on the set of Conan the Barbarian, showcasing his hands-on approach to filmmaking.

John Milius on the set of Conan the Barbarian with Arnold SchwarzeneggerJohn Milius directing Arnold Schwarzenegger on the set of Conan the Barbarian, showcasing his hands-on approach to filmmaking.

Two years later, John Milius emerged as a key figure in the USC Film School Mafia, a group of filmmakers who would redefine Hollywood. He quickly established himself as a prolific screenwriter, penning scripts for iconic films like Jeremiah Johnson, Dirty Harry (uncredited), Judge Roy Bean, Magnum Force, and Apocalypse Now. This impressive portfolio granted him the opportunity to direct his own scripts, leading to films such as Dillinger, The Wind and the Lion, Big Wednesday, Conan the Barbarian (co-written with Oliver Stone), Red Dawn, Farewell to the King, Flight of the Intruder, and Rough Riders. His work on Apocalypse Now, shared with Francis Ford Coppola, earned him an Academy Award nomination, cementing his reputation as a top-tier Hollywood screenwriter. In fact, John Milius was hailed as “the hottest screenwriter in Hollywood” on four separate occasions throughout his illustrious career.

The Lucrative World of John Milius Screenplays

The sale of his screenplay The Life and Times of Judge Roy Bean for $300,000 in 1971 was a landmark moment. This sum was almost unheard of at the time, especially considering Milius’s previous asking price was $85,000. Reflecting on this deal with Esquire, John Milius stated, “I make terrific deals. My hole card on this one was I didn’t particularly want to sell Roy Bean anyway. I had written it for my own pleasure.” This quote reveals not only his business acumen but also his artistic integrity. More significantly, the script itself showcased the distinct voice of a writer who was rapidly making his mark.

A Unique Voice Emerges: The “Gifted Barbarian”

Andrew Sarris dubbed John Milius “the gifted barbarian,” a moniker that captured the raw, untamed energy of his writing. Pauline Kael was among the first critics to recognize Milius’s singular voice. She observed it in scripts directed by Sydney Pollack (Jeremiah Johnson) and John Huston (Judge Roy Bean), though she critiqued his apparent fascination with violence and what she perceived as a glorification of lawlessness. This recognition of John Milius’s distinct authorial voice as a screenwriter challenged the prevailing auteur theory, which typically emphasized the director as the primary creative force. Milius became the gun-toting face of the Hollywood writer in the early 1970s, a figure as compelling as the characters he created.

The Milius Worldview: Morality, Myth, and Defiance

John Milius’s screenplays and films consistently present a distinct worldview. His characters adhere to a strong moral code, often standing alone against societal pressures. Martial combat and purposeful violence are recurring themes, elevated to an almost mythical level, making his characters larger than life. Milius himself succinctly described his perspective as anachronistic: “The world I admire was dead before I was born.” This statement encapsulates his fascination with historical periods and archetypal figures.

Rejecting what he saw as “the hypocrisy of the Writers Guild,” John Milius positioned himself as an industry outsider, a “God’s lonely man,” much like his own characters. He underscored the high price writers pay for conformity in Hollywood. As Milius wrote in Written By, “I’ve suffered loss in my career for not being obedient. Believe me, the loss was little compared to the fear all you elite [writers] stomach every day. When the sun sets, I can sing ‘My Way’ with Elvis, Frank Sinatra, and Richard Nixon. What is your anthem?” This powerful statement reveals his unwavering commitment to his principles and his defiance of industry norms.

Paul Newman as Judge Roy Bean in The Life and Times of Judge Roy BeanPaul Newman portraying Judge Roy Bean, a character brought to life by John Milius’s distinctive writing, showcasing the blend of lawlessness and moral code prevalent in his work.

Paul Newman as Judge Roy Bean in The Life and Times of Judge Roy BeanPaul Newman portraying Judge Roy Bean, a character brought to life by John Milius’s distinctive writing, showcasing the blend of lawlessness and moral code prevalent in his work.

Film School and the Foundations of Screenwriting

Reflecting on his formative years, John Milius credited film school, particularly his demanding teacher Irwin Blacker, with providing him with essential screenwriting foundations. “Well, I learned everything I need to know,” Milius stated about his two years at film school. Blacker’s rigorous approach focused on screenplay form. Milius recounted, “He gave you the screenplay form, which I hated so much, and if you made one mistake on the form, you flunked the class. His attitude was that the least you can learn is the form. ‘I can’t grade you on the content. I can’t tell you whether this is a better story for you to write than that, you know? And I can’t teach you how to write the content, but I can certainly demand that you do it in the proper form.’” Blacker emphasized storytelling and craft, rather than formulaic approaches. He encouraged radical creativity within the established structure, saying, “Do whatever you need to do. Be as radical and as outrageous as you can be. Take any kind of approach you want to take. Feel free to flash back, feel free to flash forward, feel free to flash back in the middle of a flashback. Feel free to use narration, all the tools are there for you to use.”

Milius distilled his screenwriting philosophy to its core: “I could teach you all the basic techniques in fifteen minutes. After that, it’s up to you.” He cited Moby Dick as the ultimate screenplay example, praising its dramatic character entrances and narrative structure. He also acknowledged Kerouac’s On the Road as an influence, appreciating its sprawling, character-driven narrative, demonstrating his appreciation for diverse storytelling styles. Both Moby Dick and On the Road, though vastly different, exemplified discipline in storytelling, according to Milius, emphasizing that “Nothing happens by accident in either of those two books.”

Apocalypse Now, a cinematic masterpiece co-written by John Milius, reflecting his epic storytelling and character-driven narratives.

Apocalypse Now, a cinematic masterpiece co-written by John Milius, reflecting his epic storytelling and character-driven narratives.

Apocalypse Now: From Script to Screen – A Kerouac-esque Journey?

When asked if his original screenplay for Apocalypse Now leaned towards the Kerouac approach, John Milius drew a parallel to Moby Dick as well. “I don’t know. You could say it’s very much like Moby Dick, too. You start with this character who’s given up on life, and suddenly they haul him out of his shower and take him to the ship. They tell him you’re gonna hunt white whale at the end of the river. I don’t know. I never thought of it that way.” He acknowledged the flowing, character-centric aspect, agreeing it was “very influenced that way.” The core idea, for Milius, was the inevitable confrontation with a monumental challenge, “somewhere there’s going to be Judgment Day, somewhere, you know, you’re gonna meet Moby Dick.”

Despite his film school beginnings, John Milius admitted Apocalypse Now wasn’t significantly developed during that period. “Not very far. I wrote two real scripts in film school, but when I came here and really started writing, I rewrote every bit of them. Neither of them were ever made, but I was able to option them. I had them rented out for like $5,000 a year.” These early scripts, though unproduced, served as valuable learning experiences and provided early financial success.

Breaking into Hollywood: Early Struggles and Lessons Learned

Leaving film school with a new wife, John Milius faced the challenge of entering the film industry. He recounted his initial eagerness for any work: “Well, I was just happy having any job at all. I was very lucky. I did very, very well from the beginning. I went to the first job I had, working for AIP for Larry Gordon, and I was amazed that I actually got paid to do this, I mean for something other than lifeguarding.” His early experiences included working for Al Ruddy at Paramount, where he wrote The Texans, a script he deemed “not very good” and unproduced.

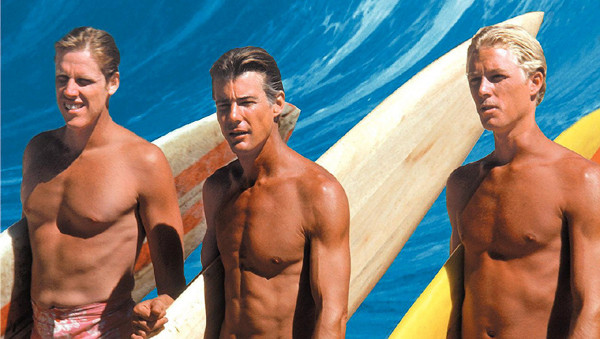

An important lesson emerged from these early assignments. “Every time I went along with something in my whole career it usually didn’t work. Usually there’s a price to pay. You think of selling out, but there is a price to pay. Usually what people want you to do is make it current.” The pressure to incorporate “cultural resonance” often led to 작품 that Milius felt were compromised and quickly dated. Big Wednesday served as a contrasting example, where resisting pressure to become more like Animal House and staying true to its original vision of “Arthurian overtones about surfers” ultimately contributed to its enduring appeal. “It wasn’t just a story about somebody trying to ride the biggest wave or something. That’s not enough.”

Gary Busey as Leroy Smith, Jan-Michael Vincent as Matt Johnson and William Katt as Jack Barlow in Big Wednesday, directed by John Milius, stands as a testament to his vision of imbuing genre films with deeper, mythic themes, transcending typical Hollywood trends.

Gary Busey as Leroy Smith, Jan-Michael Vincent as Matt Johnson and William Katt as Jack Barlow in Big Wednesday, directed by John Milius, stands as a testament to his vision of imbuing genre films with deeper, mythic themes, transcending typical Hollywood trends.

Myth in Screenwriting: Empowering the Narrative

The conversation shifted to the role of myth in screenwriting. While acknowledging George Lucas’s frequent discussions of myth, Milius was critical of its superficial application, citing Phantom Menace as an example. He asserted that writers who genuinely understand myth use it unconsciously. “Writers who really understand myth don’t use it consciously. There are very few things that are truly mythical. There’s a lot of stuff that’s famous, but very few things that are the stuff of myth and legend.”

John Milius believed classical mythology could empower a script by creating a sense of importance and resonance. “See, myth is something where you feel an importance. The writer is relating something to an important story. If the hero has the heel of Achilles or something, then you might create a slight resonance to The Iliad—then in your gut you feel that this is important.” He pointed to The Iliad‘s enduring power, arguing it stems from its ambiguous portrayal of war, “a story about war in which nobody is really sure what they’re fighting for, which makes it like all wars. Therefore it becomes myth.” He identified the Mafia and the Old West as two great American myths, both rooted in themes of promise and the pursuit of opportunity, “about promise, about coming here with nothing, and the promise over the next horizon. They’re the same story, told in different ways. One’s told in the city, one’s told in the country. That’s why we love the Mafia. We never tire of the Mafia.”

Marlon Brando as Don Vito Corleone in the Godfather, a cinematic embodiment of the American Mafia myth, a theme that resonates deeply with John Milius’s fascination with American archetypes.

Marlon Brando as Don Vito Corleone in the Godfather, a cinematic embodiment of the American Mafia myth, a theme that resonates deeply with John Milius’s fascination with American archetypes.

Writing Rituals and Process: Longhand and Procrastination

John Milius described his writing process as devoid of strict rituals, but characterized by a pattern of procrastination followed by intense focus. “No, I just like to write at the end of the day because I like to think about it all day. And usually, I’ll try to avoid thinking about it, I’ll bullshit and talk to people all day long. I’ll do various acts of procrastination and then as the sun starts to get low and the shadows lengthen, guilt wells up.” He maintained a daily output goal, “Yeah, at least six. If I feel like going for more, I go for more. But I write no less than six—in longhand.”

Milius emphasized the importance of writing in longhand, rejecting computers for the initial drafting process. “Yeah, it’s too easy to change things on the computer. You don’t have to handfit it, you know. And basically, this is hand work. There is no way to make precision parts and put them together. Every screenplay is different so it must be made by hand.” This preference for longhand underscores his belief in the craft and organic nature of screenwriting.

Nick Nolte as Learoyd in Farewell to the King, directed by John Milius, showcasing his preference for epic, hand-crafted filmmaking, much like his longhand writing process.

Nick Nolte as Learoyd in Farewell to the King, directed by John Milius, showcasing his preference for epic, hand-crafted filmmaking, much like his longhand writing process.

Early Success and Industry Perceptions of Writers

John Milius recounted his early financial success, optioning scripts straight out of film school. “Yeah. I lived pretty well on $15,000 a year back then, so $5,000 was a third of my income. If I went up to Malibu and shot a deer that cut the income down even further. I think the first year I made about $25,000. The second year I made about $40,000 or $50,000. I mean, I was as rich as a rajah.” These early scripts garnered industry attention and led to small assignments and option deals.

However, Milius noted a shift in how writers were perceived and treated in Hollywood. “I never got any assignments. I never got assignments from them. I had an agent sending me to their offices—I guess what they call “pitching” today. I hate “pitch” because it’s such an ugly term. It really describes the demeaning of the writer. Writers are treated like garbage, just stepped on and spit on.” He contrasted this with his experience writing Apocalypse Now at Warner Bros., where he felt respected and trusted. “John Calley said, ‘This guy’s a genius. Leave him alone. He’s going to do this brilliant screenplay and most of all, he’s cheap.’ Nobody knew what it was going to be. He didn’t know whether I would turn out to be a good writer. But that’s the way they treated writers then.”

Danny Glover as Cmdr. Frank, directed by John Milius, highlighting his ability to craft compelling narratives even within studio-driven projects.

Danny Glover as Cmdr. Frank, directed by John Milius, highlighting his ability to craft compelling narratives even within studio-driven projects.

Demystifying Screenwriting and the MBA Influence

John Milius lamented the “demystification of screenwriting” through books, seminars, and formulaic approaches. “A lot of that probably goes back to the demystification of screenwriting through all the books and seminars and tapes… It is mystical. All creative work is mystical. How dare they demystify it? How dare they think they can demystify it? Especially when they can’t write. These guys who write these books, what’s their great literary legacy to us? What have they done? They don’t even write television episodes.”

He criticized the MBA-driven, formulaic approach to screenwriting that prioritized structure and marketability over genuine storytelling. “A writer’s greatest fear now is not that he’s going to be no good when he sits down to write. A writer’s greatest fear is that he’s going to be brilliant and that no one will read it, that no one can read it, that no one knows the difference because they read these stupid “How to write a screenplay” books. It’s made people into idiots.” He contrasted this with the past, “In the old days the writer’s greatest fear was always, this time out, it just isn’t going to happen. I just won’t have the stuff. Now the fear is that I’ll have it, but those little jerks from Harvard Business School won’t be able to understand it.” He mocked the emphasis on formulaic questions like, “Who are you rooting for at the end of the first act?” Milius stated plainly, “I was never conscious of my screenplays having any acts. I didn’t know what a character arc was. It’s all bullshit. Tell a story.”

Milius advocated for a return to core storytelling principles, rejecting unnecessary descriptive writing in screenplays. “When I got in, you had to write all that stuff like “ext,” “day,” all the stuff that’s necessary, and then writers actually wrote, “we see so and so coming down the hall, she is a beautiful woman in her thirties and by her walk we can tell she’s a certain type…” I threw it all out. I said, “I don’t want to write that. That doesn’t tell you what the story’s about.” He emphasized focusing on impactful opening lines and setting tone through language, citing The Wind and the Lion and Apocalypse Now as examples. He lamented the current industry trend, “Today, you fool with it and they say, ‘Well this doesn’t follow the form.’ They don’t know what’s good. They don’t have any judgment. This isn’t just sour grapes. Look at the crap that’s made. I’ll put my titles up against anything these jerks produce.”

The Importance of Uncompromising Excellence and Passion

John Milius stressed the importance of artistic integrity and resisting compromise. “Never compromise excellence. To write for someone else is the biggest mistake that any writer makes. You should be your biggest competitor, your biggest critic, your biggest fan, because you don’t know what anybody else thinks. How arrogant it is to assume that you know the market, that you know what’s popular today—only Steven Spielberg knows what’s popular today. Only Steven Spielberg will ever know what’s popular. So leave it to him. He’s the only one in the history of man who has ever figured that out. Write what you want to see. Because if you don’t, you’re not going to have any true passion in it, and it’s not going to be done with any true artistry.”

Steven SpielbergSteven Spielberg, whom John Milius acknowledges as uniquely understanding popular appeal, while advocating for writers to pursue their own passionate visions.

Steven SpielbergSteven Spielberg, whom John Milius acknowledges as uniquely understanding popular appeal, while advocating for writers to pursue their own passionate visions.

While passion fuels good writing, Milius acknowledged that “a lot of tricky writing, a lot of gimmicky writing sells. That doesn’t mean it’s good.” He criticized writers who prioritize marketability over substance, “Most of the people who talk about how wonderful they are, about their great reputations and their great careers as writers, and being able to write what sells, don’t have very many credits. They may do rewrites and work occasionally, but they don’t have a body of work or a voice because nobody cares. There’s a million other people just like them.”

Jeremiah Johnson: Finding His Voice

John Milius identified Jeremiah Johnson as the turning point where he truly found his voice as a writer. “The real breaking point where I knew—and it was almost overnight—that I had become a good writer with a voice was Jeremiah Johnson. When I started working on that, it was called The Crow Killer and I knew that material. I’d lived in the mountains, I had a trapline, I hunted, and I had a lot of experiences with characters up there. So, it was real easy to write that and there was a humor to it, a kind of bigger-than-life attitude.” He drew inspiration from Carl Sandburg’s poetry, aiming for “abrupt description” and a “feeling” reminiscent of Sandberg’s work. He also cited American braggart poetry as an influence, capturing a distinct American voice. “I just realized that this was the voice that the script had to have. It was as clear as a bell. I knew that writing was particular to me.”

Despite initial skepticism from Sydney Pollack and Robert Redford, Milius’s unique voice proved indispensable. “Sydney Pollack and Robert Redford didn’t trust me very much at first, though. I wasn’t really housebroken in those days. I was a wild surfer kid, you know, and they preferred their writers to be more intellectual. And so they would get the intellectual writers to try and rewrite it and they’d have to hire me back because none of those guys could write that dialogue. None of those guys understood that stuff. They didn’t understand the mountains. They didn’t understand what a mountain man was. I love mountain men. I’d love to write a mountain man story today.” He realized the power of humor and absurdity in his writing, exemplified by lines like, “I, Hatchet Jack, do leaveth my Barr rifle to whatever finds it. Lord hope it be a white man.”

Josh Albee as Caleb and Robert Redford as Jeremiah Johnson in Jeremiah Johnson, a film that solidified John Milius’s distinctive voice as a screenwriter, rooted in his personal experiences and appreciation for American folklore.

Josh Albee as Caleb and Robert Redford as Jeremiah Johnson in Jeremiah Johnson, a film that solidified John Milius’s distinctive voice as a screenwriter, rooted in his personal experiences and appreciation for American folklore.

A Pivotal Decision: Choosing Art Over Commerce

John Milius recounted a pivotal career decision: choosing to write Apocalypse Now for a smaller sum over a more lucrative rewrite assignment. “No, I wrote it for nothing. I wrote it for $5,000. And then I was offered a deal to rewrite a Western script [Skin Game] for $17,000. But Francis [Ford Coppola] had this Zoetrope deal at Warner Bros. and asked me, ‘How much do you need to live on?’ I said, ‘$15,000.’ He said, ‘Well, I’ll get you $15,000 to do your Vietnam thing. You and George [Lucas],’ because George was going to direct it.” This decision to pursue his own artistic vision, despite financial incentives to do otherwise, shaped his career trajectory. “That was the most important decision I made in my life as a writer. That sort of steered me onto the path of doing my own work and being a little more like a novelist. Today I see writers making the exact opposite decision, taking the $17,000 again and again.”

He observed a trend of writers prioritizing immediate financial gain and career advancement over artistic fulfillment. “I see them always taking the two grand more because it’ll help their careers, they’ll get to work with a real big producer, they’ll be in a big office, they will be working on a greenlit movie, and it’s going to star someone who’s hot. They always take that job, every time. Whereas I tackled an unpopular subject that no one was going to make a movie about where the chances were really slim that I could pull it off. There was no book, nothing but me and the blank page. And that was wonderful because I had followed my heart. One of the nicest times in my life was writing Apocalypse Now.”

Marlon Brando as Colonel Walter E. Kurtz in Apocalypse NowMarlon Brando as Colonel Kurtz in Apocalypse Now, a role conceived in John Milius’s script, representing the artistic risks he embraced early in his career.

Marlon Brando as Colonel Walter E. Kurtz in Apocalypse NowMarlon Brando as Colonel Kurtz in Apocalypse Now, a role conceived in John Milius’s script, representing the artistic risks he embraced early in his career.

Creative Freedom and Character Development

John Milius credited Francis Ford Coppola with granting him creative freedom during the Apocalypse Now writing process. “None. Francis was very good about that. Francis wanted us to be artists, like him. He didn’t want to interfere with anybody. He wanted you to go out and write your scripts and if you couldn’t do it, if you went to him and whined and said, ‘Gee, I need some help,’ he didn’t have much regard for that. You know, he expected you to be independent and he was giving you a wonderful opportunity to be independent of anybody else. But people did go to him and complain and whine all the time. All the time.”

Milius described his approach to character development as organic and intuitive. “I never think about any story too much. I sort of know where they’re going and I know specific things are going to happen to them along the way, but I don’t know when they go do this and when they go do that, because if you do know all that, for me anyway—I mean other people write it all down on little cards—I don’t want to know what’s going to go on. I want the people to surprise me each day. I have no idea how I’m going to make transitions from one scene to another. I have no idea where they’re really going to go and the thing I just wrote.” He emphasized understanding characters’ backgrounds and mannerisms to inform their dialogue and actions, using the example of a New Jersey character using specific slang.

Martin Sheen as Captain Benjamin L. Willard in Apocalypse NowMartin Sheen as Captain Willard in Apocalypse Now, a character whose journey was organically developed by John Milius, allowing for surprises and spontaneity in the narrative.

Martin Sheen as Captain Benjamin L. Willard in Apocalypse NowMartin Sheen as Captain Willard in Apocalypse Now, a character whose journey was organically developed by John Milius, allowing for surprises and spontaneity in the narrative.

Revisiting Apocalypse Now and Embracing Ambition

John Milius explained that he didn’t need extensive rewrites on Apocalypse Now because he intentionally kept the narrative open and fluid. “I didn’t need to because I had left it open. I knew what the beginning would be. I knew sort of what the end would be, and I knew certain things would happen in the middle. It was the same with Apocalypse Now. I knew where it was going to end, I knew Kurtz was at the end of the river, but I didn’t know how we were going to get to him. I knew somewhere along the line there would be the first obstacle, this character Kharnage [Kilgore in the film] who was really like the Cyclops in The Iliad, and then there are the Sirens, who are Playboy bunnies. But basically I didn’t know where I’d find them, or what would happen.” He described his desire to immerse the characters in the chaotic reality of the Vietnam War, avoiding generic war scenes and instead focusing on the “insane and most intense” aspects.

Milius emphasized Coppola’s encouragement to push creative boundaries. “Absolutely. Absolutely. You have to also discipline yourself to pull it in afterwards and make sense of it. But you’ve really got to go for it.” He criticized the lack of ambition in contemporary films, particularly independent films, finding many to be narrowly focused and lacking scope. “The worst thing about today’s films is the complete lack of ambition. I mean, look at all these independent films that should be interesting. Most of them are about a bad dope deal in the Valley. The rest of them are about a homosexual love affair that’s misunderstood. There’s really just not a lot of ambition there. I find the violent films to be particularly onerous. There’s a lot of shooting and killing, and people turning on each other and they’re kind of supposed to be the film noir of the ’90s, but they’re not. They’re all about punks. Everybody gets killed and you sit there and say, ‘God, I’m glad that person got wasted,’ you know. ‘At least I got to see it.’”

Punks killing each other: Steve Buscemi as Mr. Pink and Harvey Keitel as Mr. White in Reservoir Dogs, a film representing the kind of violent, punk-centric narratives that John Milius critiques for their lack of deeper meaning and consequence.

Punks killing each other: Steve Buscemi as Mr. Pink and Harvey Keitel as Mr. White in Reservoir Dogs, a film representing the kind of violent, punk-centric narratives that John Milius critiques for their lack of deeper meaning and consequence.

Rewriting and Collaboration on Apocalypse Now

John Milius clarified his rewriting process with Coppola on Apocalypse Now, emphasizing that it occurred during production, not after the initial draft. “No. People didn’t do that in those days. They didn’t sit there and interfere. They took things for what they were, and when Francis and I rewrote the script it was when it was being made. The script remained the same ‘til Francis really decided to make the movie, and then we went in and reexamined everything. That was part of a process.”

He felt he received adequate credit for his writing on Apocalypse Now, acknowledging Coppola’s directorial contribution. “Oh, yeah. I get full credit for the movie. I mean, I get credit for writing the movie. And Francis gets the credit for directing, which he certainly deserves because no one could have—if I’d have made it or anybody would have made it, it would have never been as good as that. But I get the credit and it’s a Milius movie. It’s not a Coppola movie. A Coppola movie is The Godfather.” He recognized Coppola’s unique ability to elevate the material through his directorial vision, drawing a parallel to Mankiewicz and Welles’s collaboration on Citizen Kane. “But what is Citizen Kane without Orson Welles making it?”

He addressed the perception, fueled by Hearts of Darkness, that Coppola heavily improvised the script during filming. “No, I think I get enough credit. Hickenlooper’s just trying to kiss Francis’s ass all the time. When the movie first came out, Francis tried to hog all the credit, but not any more. He gives the credit to me and to everybody else, because everybody who worked on that movie suffered and has credit for it. It stained everybody’s lives. We were messing with the war and war is sacred. There’s something about that war. It’s just, you know, obscene and sacred. You mess with it, you’re going to get your life fucked with.”

Apocalypse Now as a “Young Man’s Film” and Hollywood’s Youth Obsession

John Milius reflected on Apocalypse Now as a product of a specific time and mindset, calling it “a young man’s film.” “I’d be different, you know. I’d be a lot different. Apocalypse had a certain outrageousness to it. It went headlong into things. The worst thing I could do now would be to try to do something like Apocalypse. You can’t go back and recapture that power.”

He criticized Hollywood’s focus on youth and its neglect of powerful, ambitious storytelling. “It seems to me a real tragedy that Hollywood has such a focus on youth and young writers in touch with today’s culture, but they aren’t looking for those kinds of powerful stories. They want Big Daddy II or something.” He attributed this to a lack of ambition and engagement with real-world challenges among younger generations. “Well, those people are mostly not capable of delivering real power either. Youth today has a sense of rightful entitlement. They don’t have ambition. They don’t have a draft. They don’t have a Vietnam. They don’t have any of this. They’re not going to face that kind of stuff, and they don’t want any part of it. So they don’t make it for themselves either. Their idea of great adventure is extreme sports, diving off bridges with bungee cords. They don’t go off and do something real. There are no youth movements. There aren’t any revolutions being fought today. They’re all interested in getting their piece. You know, being where it’s at. Being hip. Looking good. Getting that BMW.”

Adam Sandler as Donny in That, unofficially linked to Big Daddy, exemplifies the kind of youth-focused, less ambitious projects that John Milius critiques in Hollywood.

Adam Sandler as Donny in That, unofficially linked to Big Daddy, exemplifies the kind of youth-focused, less ambitious projects that John Milius critiques in Hollywood.

Violence in Films and Moral Codes

As an NRA board member and filmmaker known for violent films, John Milius addressed the debate surrounding violence in media. “You’re sitting in an interesting position in the debate on violence in our society. As both a board member of the NRA and also a filmmaker—the liberals are shooting one way and the conservatives the other. And it would seem like you’re in the crossroads there.” He responded, “Or in the crossfire! Any way I move I get hit, but I’m used to that.”

He acknowledged the negative impact of gratuitous violence in films, agreeing with critics “that they’re absolutely right about the films. I think there’s nothing you can do about it except embarrass these people into not making these films that are cheap exploiters of violence. I think it’s part of the decay of our society. You could look at the Roman games as something similar—they started out as admittedly brutal athletic contests, where people went to see great skill, and then they turned into sadism. And that’s what’s happening to us. There is no doubt that the approach to violence in most movies and in video games desensitizes children and turns them into heartless killers.” However, he defended his own violent films by emphasizing their moral code and consequences for actions. “I make violent films and I’ll continue to make violent films. But my films have a strict code of morality, as strict as the Code of the Samurai. There are extreme consequences for action in my films. I mean, my characters pay terrible consequences for doing certain things. For example, Jeremiah Johnson goes through the Indian graveyard and he loses his family, he’s cast into the winds for the rest of his life. He may be a legend but he has no place to sleep. And, you know, there’s a tremendous consequence for violence. There’s a tremendous consequence for action of any kind, good or bad. That’s what the world is.” He contrasted this with films like Eraser and Die Hard, which he felt lacked consequences. “But in movies like Eraser or Die Hard III or even Die Hard, there’s no consequences for actions. It’s all bullshit.” He placed blame on filmmakers, not gun laws, for societal issues related to violence. “These filmmakers deserve what they’re getting. They deserve it much more than the gun lobby. We had all the laws. Those kids at Columbine broke the law.”

Arnold Schwarzenegger as U.S. Marshal John Kruger in Eraser, a film John Milius uses as an example of consequence-free action movies, contrasting with his own approach to depicting violence with moral weight.

Arnold Schwarzenegger as U.S. Marshal John Kruger in Eraser, a film John Milius uses as an example of consequence-free action movies, contrasting with his own approach to depicting violence with moral weight.

Dirty Harry and Leading Public Consciousness

John Milius discussed his uncredited rewrite work on Dirty Harry, asserting, “Oh, I brought the whole thing… I should have gotten the full credit.” He explained his lack of credit was due to procedural issues with the Writers Guild arbitration, not a lack of contribution. He also mentioned Terry Malick’s draft after his own, suggesting Malick also deserved credit. Despite the lack of official credit, Dirty Harry and Magnum Force became associated with his distinctive style.

When asked about influencing public consciousness with these films, Milius felt he was “leading, definitely.” “No, I felt I was leading, definitely. Because that’s what was fun about it, writing this outrageous story of Dirty Harry, you know, who breaks the law and is a criminal who’s on our side. He will commit murder, if necessary, to get the job done, you know. And then you do the next one that’s the reverse of that. You’ve got a whole bunch of young guys who are sort of a death squad who are going out and doing that and where do you draw the line, you know? So it was fun to do the flip side of that.” He saw Dirty Harry as a consistent character across both films, emphasizing his “God’s lonely man” archetype, isolated and dedicated solely to his duty. “The thing that I liked about him was he was God’s lonely man. The way I conceived him was his only relationships were with hookers, and that he didn’t have too many friends. He had partners, you know, who usually got killed. When he went to his apartment, there was nothing in his apartment except a couple of awards on the wall for meritorious service or something, some old food in the ice box, and a bed to sleep on, and maybe another room where there was a bench to clean his gun. That was all Harry had.”

Clint Eastwood as Harry in Dirty HarryClint Eastwood as Dirty Harry, a character largely shaped by John Milius’s vision, embodying the “God’s lonely man” archetype and challenging societal norms.

Clint Eastwood as Harry in Dirty HarryClint Eastwood as Dirty Harry, a character largely shaped by John Milius’s vision, embodying the “God’s lonely man” archetype and challenging societal norms.

Clint Eastwood as Harry in Magnum Force, further exploring the Dirty Harry character, showcasing John Milius’s interest in morally complex protagonists operating outside conventional boundaries.

Clint Eastwood as Harry in Magnum Force, further exploring the Dirty Harry character, showcasing John Milius’s interest in morally complex protagonists operating outside conventional boundaries.

Hollywood Ethics and the Blank Page

John Milius offered a cynical yet pragmatic view of Hollywood ethics: “You’ve said that in Hollywood it’s okay to fuck people over and to lie to them. How do you think someone should approach working in this industry?” He clarified, “It’s okay to fuck people over and lie to them once you’ve established the ground rules. But you know, you must have a code of behavior, a code of honor. If you don’t have a code of behavior, you will not be strong. You know, you don’t have that code of behavior because there’s an absolute morality or because the other guys can even respect it. It’s because if you don’t have something to measure yourself by, you have no way of gaining strength. If everything is permissible, if it’s situational ethics, there’s no way to gain any strength of character. And it isn’t for Hollywood. It’s for you. It’s so you can survive and do good work. They don’t give a shit. It’s just so you can survive and do good work. It won’t get you anything. No one else will ever recognize it. They’ll think it’s a pain in the ass. But it gives you strength of character and you have to have strength of character to finish what you start.”

He emphasized the ultimate importance of facing “the blank page” as a writer. “You know, you can steal somebody’s work, but sooner or later you have to face the blank page. And when you face the blank page, you’d better have the right stuff. As a writer, that’s the most important thing. There’s nothing else that I could say about writing that’s as important as that. I mean, you can sit there and you can talk about technique, you can talk about feelings of people, you can talk about being smart, clever, you can talk about these guys like this guy Ron Bass who has all these people writing for him. All that shit means nothing because when you face the blank page, when you’re sitting there and looking at the pad with those lines across it, you’ve got to have the stuff to call upon. And you have to build the stuff, little by little, out of something. Out of human experience, out of a lot of other things. That mad confidence has got to come from somewhere.”

Ronald BassRonald Bass, mentioned by John Milius in the context of writers who may rely on external help, contrasting with Milius’s emphasis on individual strength when facing the blank page.

Ronald BassRonald Bass, mentioned by John Milius in the context of writers who may rely on external help, contrasting with Milius’s emphasis on individual strength when facing the blank page.

Screenwriter’s Duty: Honesty and Defiance of Societal Codes

John Milius defined a screenwriter’s duty to the audience as “a certain honesty.” “What does a screenwriter owe his audience beyond a satisfying tale? A certain honesty. A screenwriter has to be able to put it on the line. I didn’t have another agenda. I didn’t do something because I thought it was going to make me rich. I didn’t do something because I thought it was going to make me loved. I didn’t do something because I thought it was going to be hip. I did the best I could and put out something that I believed in.” He explicitly rejected societal codes as a guiding principle, “Not the code of society… Absolutely not. I mean, the code of society is almost always wrong. You know, the code of society is the code of the lemming. The lemming or the Yuppie. The stinking bureaucrat.”

Flamboyance and the Showman in Hollywood

John Milius acknowledged the role of flamboyance in Hollywood success. “You have a certain flamboyance. Do you think that helped you in building your career in Hollywood? Yeah. I think that all the people who are successful in Hollywood have a flair for flamboyance. Francis certainly does, he’s the most flamboyant of all. And I guess you could say Spielberg has a flamboyance in a way. If you don’t have that kind of flair for being a showman, for being an entertainer, then you’re not going to live with this business very well. But to be truly flamboyant you have to be about something.” However, he critiqued Spielberg’s later work as sometimes lacking substance, “It’s interesting that you bring up Spielberg because many of his films have been about very little. You mean like The Lost World… yeah, I don’t like those movies and I’ve never really understood the success of those “roller-coaster ride” movies, but he’s amazingly good at that. He’s really skilled as a director.” Despite his criticisms, Milius recognized Spielberg’s directorial talent, citing Saving Private Ryan. “For example, Saving Private Ryan is filled with scenes that just don’t work. But he makes them work… Spielberg makes it work through the power of his skills and you’ve got to give him credit. I was absolutely stunned by how he was able to take things that on paper were just disastrous, even boring, and made them exciting. And, of course, the best parts of the film, where he really let himself loose, were the battles.”

Matt Damon as Private Ryan in Saving Private Ryan, a film where John Milius acknowledges Steven Spielberg’s directorial skill in elevating potentially weak material, particularly in action sequences.

Matt Damon as Private Ryan in Saving Private Ryan, a film where John Milius acknowledges Steven Spielberg’s directorial skill in elevating potentially weak material, particularly in action sequences.

Career Longevity and the Anonymity of Rewrite Work

When asked about writers building lasting bodies of work, John Milius pointed to Paul Thomas Anderson as a contemporary example. “Can you think of any writers who are building a body of work that’s discernible as their own? Paul Thomas Anderson… The writer/director.” He expressed concern about the lack of career longevity for screenwriters in the current industry. “Writers… no. None at all. Many writers in this business are afraid to just write, to do different things. Because the business is such a prestige-oriented, posturing enterprise, people feel that everything they write has got to be special. The idea is that every time I write I should be in terror because of how good I’m supposed to be. Instead, my attitude that is I should go out and write more… That’s true. That’s what I’ve been saying. I’ve got twenty-three, twenty-four credits. I’m probably the last writer that’ll ever have twenty-four credits. Because the system is such that it just isn’t going to happen anymore.”

He accepted the anonymity of rewrite work as a pragmatic part of the profession. “Do you find the anonymity of rewrite work exasperating? I don’t even think about it. You take the job because it’s money and then hopefully within the job you get to do a couple of scenes where you can really, you know, you can do good riff. Like a musician, you get a couple of good riffs and it feels good, and then you just take the money and go off to another gig.”

There Will Be Blood, written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson, written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson, representing a contemporary writer-director John Milius admires for building a distinct body of work.

There Will Be Blood, written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson, written and directed by Paul Thomas Anderson, representing a contemporary writer-director John Milius admires for building a distinct body of work.

Cable Movies and Industry Currency: Rough Riders

John Milius dismissed the idea that directing cable movies provided industry leverage, citing his own experience with Rough Riders. “Does writing and directing a movie on cable give you currency in the Industry? None at all. Absolutely zero. Nobody in the business saw Rough Riders, and I don’t really care. I’m nearing the end of my career, so I don’t really give a shit. You know, I’ve got enough to get me through, and I’m more concerned with the work I do, whether or not I get to tell a sacred story of the Marine Corps, whether I get to tell the Curtis LeMay story.”

Rough Riders, a cable movie directed by John Milius, illustrating his point about the limited industry impact of such projects despite personal artistic fulfillment.

Rough Riders, a cable movie directed by John Milius, illustrating his point about the limited industry impact of such projects despite personal artistic fulfillment.

Making Material His Own: Rewriting Red Dawn

John Milius described his approach to rewriting scripts he directed, emphasizing the need to find personal connection within the material. “You’ve rewritten a lot of screenplays by other writers for the films you’ve directed. How do you go about making the material your own? You have to find something in it that you really like.” He recounted his experience with Red Dawn, where he significantly altered the original script. “Because something like Red Dawn, which is very much your movie, was written by… An original writer…and he was very nice throughout the whole process and then he slammed the movie when it came out. So I just wrote him out of the human race.”

He described his assertive approach to rewriting Red Dawn, informing the original writer of his intention to make it his own. “No, they came to me from MGM and said, ‘We want you to direct this. So I brought the writer in and said, ‘This isn’t going to be easy for you to take because, you know, you’re kind of full of yourself, but I’m going to take this and I’m going to make it into my movie. And you’re just going to have to sit back and watch, and it may not be too pleasant. My advice is to take the money you have and spend it on a young girl. Enjoy getting laid and write another script. Because this isn’t going to be fun to watch.’” He transformed the script from a Lord of the Flies-esque story into a resistance narrative with contemporary resonance, “His script was kind of like Lord of the Flies, and I kept some of that, but my script was about the resistance. And my script was tinged by the time, too. We made it really outrageous, infinitely more outrageous than his vision. And to this day, it holds up, because people ask, ‘What’s that movie about?’ And I say that movie’s not about the Russians, it’s about the federal government.”

Patrick Swayze as Jed, C. Thomas Howell as Robert and Charlie Sheen as Matt in Red Dawn, directed by John Milius, showcasing his transformative approach to rewriting, making the film distinctly his own and imbuing it with his personal and political perspectives.

Patrick Swayze as Jed, C. Thomas Howell as Robert and Charlie Sheen as Matt in Red Dawn, directed by John Milius, showcasing his transformative approach to rewriting, making the film distinctly his own and imbuing it with his personal and political perspectives.

Collaboration and Mentoring: A Lonely Profession

John Milius described limited collaborative writing experiences, mentioning The Devil’s 8 with Willard Huyck and mentoring young writers. “Have you ever worked “in the room” with another writer on a script? Movie Poster for The Devil’s 8… Years and years ago when I did The Devil’s 8 [with Willard Huyck]. And then I work with young writers. I give them ideas sometimes if I’m overseeing a project, but I haven’t seen very many writers who ever can really deliver.”

He echoed Coppola’s approach to fostering writer independence, advocating for minimal interference and maximum creative freedom. “What’s the best atmosphere for a writer to work in? Well, I think Francis was right. I think that you’ve got to say to the guy, ‘Go out and do your best and I’ll be here to help you. You can bounce stuff off, but I’m not going to be here to pick you up. I’m not going to be here to tell you what to do.’ Because the minute you start telling them what to do, you’ve lost.” He shared advice from John Huston about the dangers of imposing one’s personality on creative collaborators. “[John] Huston told me something that was very interesting. He said, ‘You have a very strong personality and you can impose that on other people.’ He said, ‘You can destroy people right and left by imposing your personality on them, because you just have a dominant personality.’ He said, ‘I have a dominant personality and I destroy actors all the time. And I enjoy it because I’m a sadist. But it’s not a good thing to do to get the best creative work out of people.’”

Milius lamented the lack of mentoring in Hollywood, describing it as “a very lonely place.” “Is there enough mentoring done in Hollywood? No. Hollywood is a very lonely place. It’s such a competitive environment. I started out with a bunch of friends who went to school with me, but it became a very competitive place. Who has got the biggest grosses, who gets the biggest salary, who is on the “A” list, who’s hot and who’s not? So much so there is no dialogue among artists. We’re totally out there like the mountain men, looking up every little crevice to see if there’s somebody waiting with a rifle.”

The Writers Guild logo, representing an organization John Milius critiques for its lack of support for writers with unique voices and perspectives.

The Writers Guild and Being a “Yeti”

John Milius expressed strong criticism of the Writers Guild, feeling they had consistently marginalized him throughout his career. “The Writers Guild should encourage more of a community among writers… Everybody hates the Writers Guild, me most of all. The Writers Guild has treated me throughout my career as a non-person, deliberately denying me credit. They can see me as some sort of right-wing character that’s a threat to western civilization, a threat to good liberal western civilization anyway. And I know that. I know that for a fact. They were always sort of that way. I probably did my part. I probably shoved it in their faces, you know. And I do love the fact that I’m not an intellectual. I mean, people ask, ‘Where did you go to school?’ I didn’t go to Harvard, you know. I went to USC. I remember on The Wind and the Lion, Candy Bergen said, ‘I can’t believe that just some surfer wrote this.’ I said, ‘Smile when you say that.’”

He believed the Writers Guild should champion writers with original voices like his. “You would think the Writers Guild would want to encourage writers who have a voice, who are out there saying something original… I would think that the Writers Guild should take me, first of all, and say, ‘This is an endangered species. We should do everything we can to save and protect John Milius, the Yeti. There is only one Yeti and we should save and protect him. We should form a committee to save and protect John Milius.’”

Despite feeling “blacklisted” and facing industry challenges, John Milius maintained his defiant persona. “Well, they might form a committee. I mean, they’re big on that…You’ve said that you’ve felt blacklisted from the Industry. Do you still feel that way? Like I say, I’m the only Yeti they’ve got. I’m still at large. Are you still a dangerous man? I don’t know. I’m getting old. But I’m still a Yeti.”

Candice Bergen as Eden Pedecaris and Sean Connery as Mulai Ahmed er Raisuli in The Wind and the Lion, a film written and directed by John Milius, showcasing his unique voice and challenging conventional Hollywood narratives, despite industry and critical pushback.

Candice Bergen as Eden Pedecaris and Sean Connery as Mulai Ahmed er Raisuli in The Wind and the Lion, a film written and directed by John Milius, showcasing his unique voice and challenging conventional Hollywood narratives, despite industry and critical pushback.

John Milius remains a significant figure in Hollywood, not just for his films, but for his uncompromising vision, his distinct voice, and his unwavering commitment to his craft. His journey, filled with both critical acclaim and industry battles, offers valuable lessons for aspiring screenwriters and filmmakers who dare to be original and true to themselves.

This article is based on an interview that first appeared in Creative Screenwriting volume 7, #2