Illuminated Portrait of King John of England from the 14th Century

Illuminated Portrait of King John of England from the 14th Century

John, often known as John Lackland, reigned as King of England from 1199 to 1216. His rule is widely regarded as one of the most tumultuous in English history, marked by military failures, financial exploitation, and ultimately, the forced signing of the Magna Carta. His reign was a pivotal moment in the development of English monarchy and law, setting precedents that continue to resonate today.

Early Life and Path to Kingship

Born around 1166, John was the youngest son of King Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. Favored by his father, he earned the nickname “Lackland” as he was initially not expected to inherit significant territory. Henry II attempted to provide for John through marriages and land grants, a plan that sparked rebellion among John’s elder brothers. Despite these early provisions, including the Lordship of Ireland, John’s early political career was marred by youthful indiscretions and a reputation for irresponsibility.

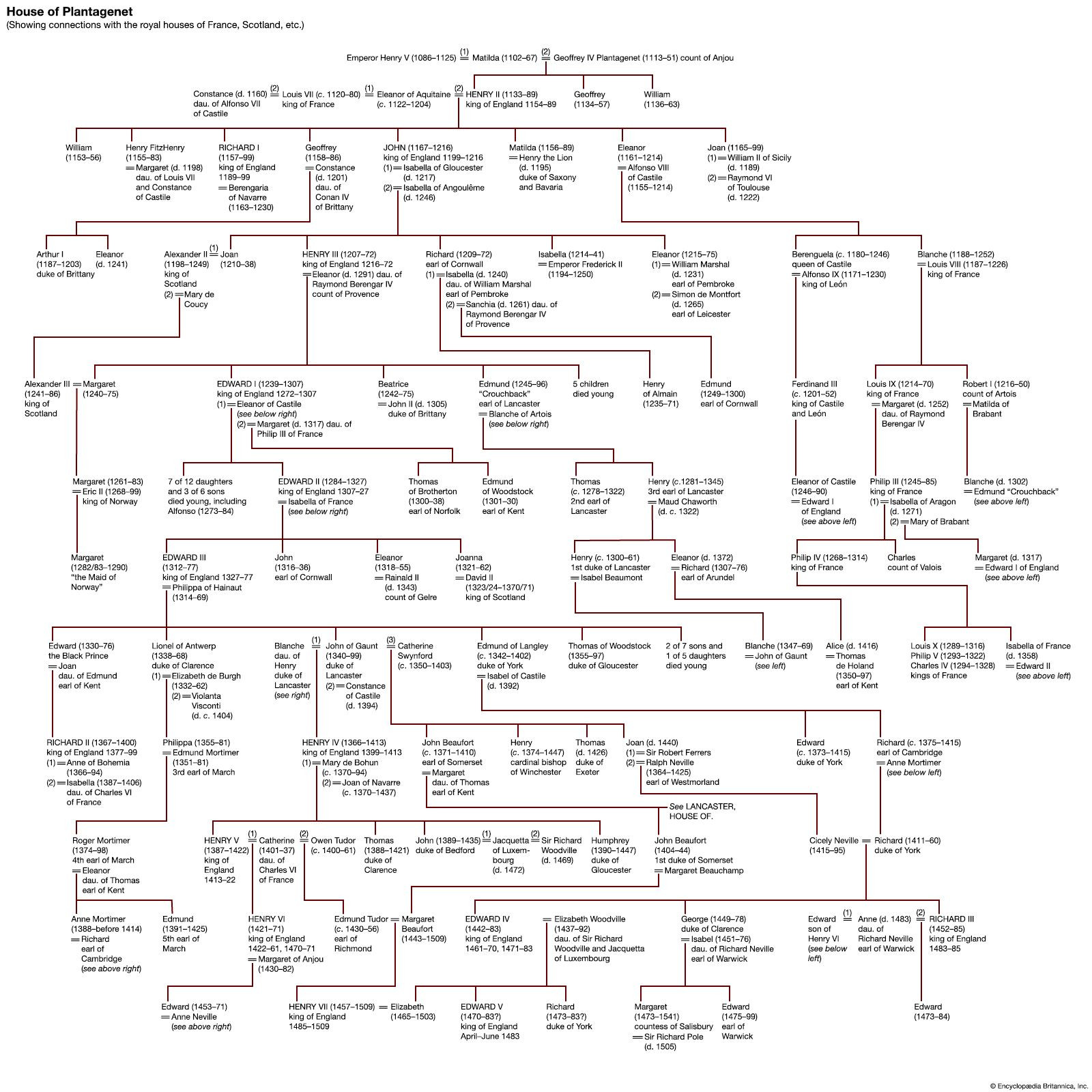

The House of Plantagenet: Royal Dynasty of King John and English Monarchs

The House of Plantagenet: Royal Dynasty of King John and English Monarchs

His relationship with his brothers was complex. While initially siding with his father against Richard I, John later switched allegiance to Richard. Upon Richard’s ascension to the throne in 1189, John was granted significant titles and lands, including Count of Mortain and Lord of Ireland. However, the question of succession soon overshadowed these gains. Richard’s recognition of Arthur of Brittany, John’s nephew, as heir apparent in 1190 ignited John’s ambition and set the stage for future conflict. John’s subsequent actions, including breaking his oath and returning to England, demonstrated his determination to challenge the established line of succession.

When Richard was imprisoned in Germany in 1193, John allied with King Philip II of France to seize control of England, highlighting his willingness to exploit any opportunity to advance his claim to the throne. Although this attempt failed, and John was initially banished upon Richard’s return, he was eventually reconciled with his brother and designated as Richard’s heir after Arthur was surrendered to Philip II in 1196.

Ascending the Throne and Continental Losses

Following Richard I’s death in 1199, John’s claim to the throne of England was contested but ultimately successful. While the principle of representative succession favored Arthur, it was not universally accepted at the time. John was invested as Duke of Normandy and crowned King of England in May 1199. However, Arthur, supported by Philip II, was recognized as Richard’s heir in Anjou and Maine. The Treaty of Le Goulet in 1200 formally recognized John as heir to Richard’s French possessions, but only at the cost of significant financial and territorial concessions to Philip, foreshadowing the challenges John would face in defending his continental territories.

King John of England Hunting: 14th-Century Manuscript Depiction

King John of England Hunting: 14th-Century Manuscript Depiction

The fragile peace with France soon dissolved, triggered by John’s controversial second marriage to Isabella of Angoulême in 1200. This political marriage, intended to secure John’s position in Poitou, instead provoked rebellion by the Lusignan family, who appealed to Philip II. John’s refusal to answer Philip’s summons led to war. Despite an initial victory at Mirebeau in 1202, where Arthur of Brittany was captured, John ultimately lost Normandy by 1204. By 1206, Anjou, Maine, and parts of Poitou had also fallen to Philip II. These losses were a major blow to John’s prestige and significantly diminished the Angevin Empire, marking a turning point in the balance of power between England and France.

Reign in England and the Magna Carta

The loss of continental territories forced King John to focus his attention on England. This period saw a shift in his style of governance, characterized by more direct and arguably more oppressive rule. To finance his attempts to regain his French lands and to consolidate his power, John implemented ruthlessly efficient and often unpopular financial measures. These included heavy taxation, increased exploitation of royal forests, and aggressive enforcement of feudal prerogatives. These policies, while effective in raising revenue, alienated the English barons and fueled growing discontent.

King John: Portrait of the Controversial English Monarch

King John: Portrait of the Controversial English Monarch

The barons’ resentment culminated in open rebellion. In 1215, they presented King John with a charter of demands aimed at limiting royal power and protecting their rights. After initial resistance, John was compelled to seal the Magna Carta at Runnymede on June 15, 1215. The Magna Carta, while initially intended to address the grievances of the barons, became a landmark document in the history of English law and liberty. It established principles such as due process, limited government, and the rule of law, principles that would have a lasting impact on the development of constitutional government.

Despite sealing the Magna Carta, King John quickly sought to circumvent its provisions, leading to renewed conflict and the First Barons’ War. The war was still ongoing when John died on October 18 or 19, 1216. His death paved the way for his young son, Henry III, to ascend the throne, and the Magna Carta was reissued in modified forms during Henry’s reign, solidifying its place in English legal and political tradition.

Legacy of King John

King John remains a controversial figure in English history. Viewed by some as a tyrannical and incompetent ruler due to his military failures and oppressive policies, he is also recognized for the unintended consequences of his reign. His financial and political pressures directly led to the Magna Carta, a document that, despite its origins in baronial self-interest, became a cornerstone of English and subsequently, global concepts of liberty and justice. While his reign was marked by loss and conflict, it ultimately contributed to shaping the future of the English monarchy and the development of constitutional principles.