King John, often remembered as one of England’s most contentious rulers, reigned from 1199 to 1216. His reign, part of the Plantagenet dynasty, was marked by significant conflict and change, both domestically and on the continent. His story is crucial to understanding the evolution of English monarchy and law, particularly due to the events that led to the sealing of the Magna Carta. This exploration delves into the life and times of King John, examining his tumultuous reign and lasting impact.

John of England

John of England

King John of England, depicted in a 14th-century illumination, highlighting the medieval context of his reign.

Early Life and Rise to Power

Born around 1166, John was the youngest son of King Henry II and Eleanor of Aquitaine. Unlike his elder brothers, John was initially nicknamed “Lackland” by his father, as he was not expected to inherit significant territories. Henry II, however, showed considerable favor towards John, attempting to secure lands for him through marriage, which sparked resentment from his older siblings. Despite early provisions and the Lordship of Ireland granted in 1177, John’s youthful impetuosity and perceived irresponsibility created a negative impression. His father’s continued preference for him strained relations within the royal family, contributing to the rebellion led by his elder brother Richard I in 1189. In a surprising turn, John sided with Richard against their father, demonstrating early political maneuvering.

Upon Richard I’s ascension to the throne in 1189, John’s fortunes improved dramatically. He was made Count of Mortain, confirmed as Lord of Ireland, and granted substantial English lands and revenues. However, the question of succession soon overshadowed these gains. Richard recognized his nephew Arthur of Brittany, son of John’s deceased brother Geoffrey, as his heir. This decision placed John in direct rivalry with Arthur. Despite pledging not to enter England during Richard’s Crusade, John returned and challenged the authority of Richard’s appointed chancellor, William Longchamp, demonstrating his ambition and willingness to defy oaths for political advantage.

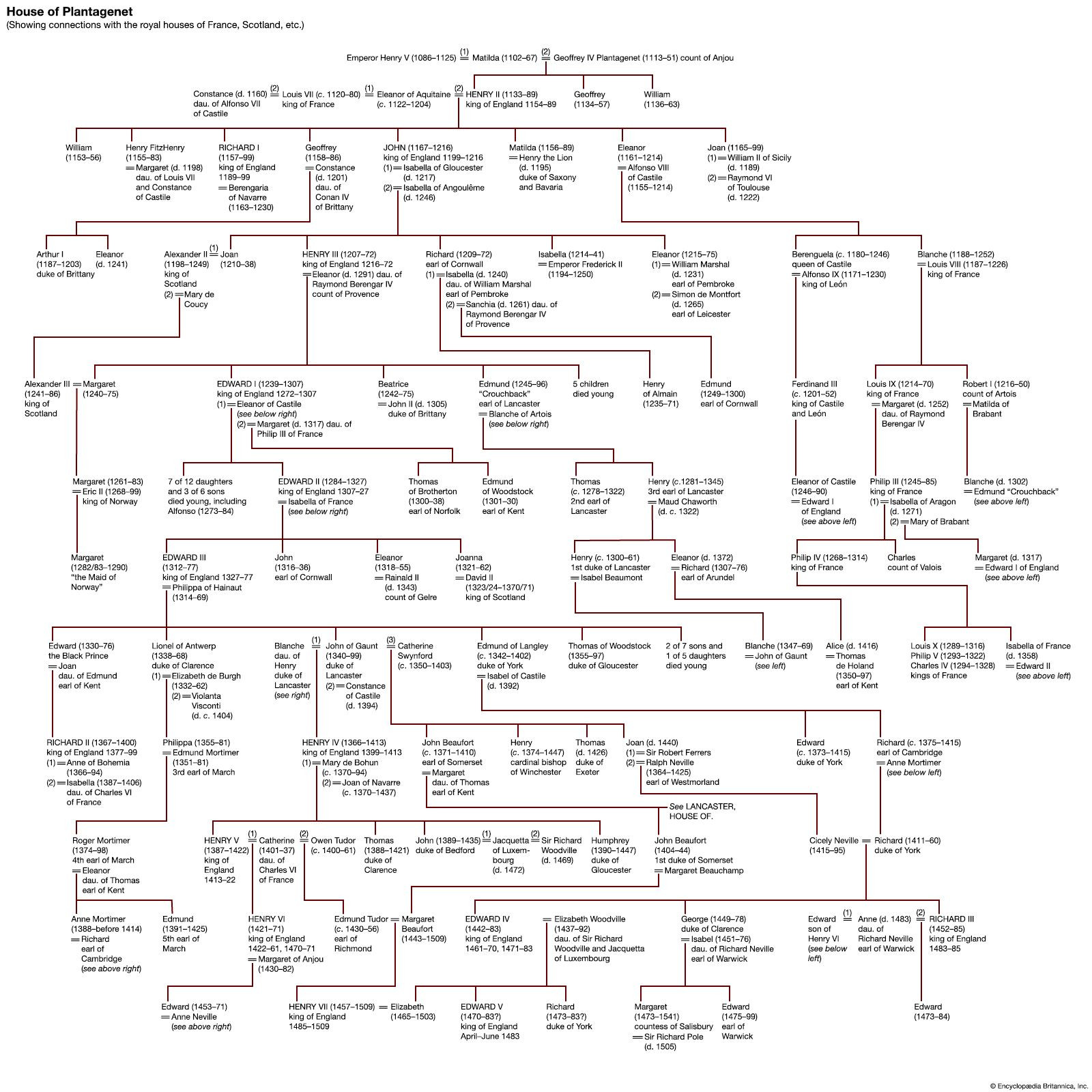

House of Plantagenet

House of Plantagenet

The House of Plantagenet, the royal dynasty to which King John belonged, showcasing his lineage and the broader historical context.

When Richard was captured in Germany on his return from the Crusade in 1193, John allied with King Philip II Augustus of France, attempting to seize control of England. This act of treachery further solidified his image as opportunistic and untrustworthy. Though initially unsuccessful, John continued to plot with Philip. Richard’s return in 1194 led to John’s banishment and dispossession. Reconciliation with Richard followed in 1195, and John regained some territories, but full rehabilitation only occurred after Arthur was surrendered to Philip II in 1196. Richard then surprisingly named John as his heir, setting the stage for his ascension to the English throne.

King of England: Reign and Conflicts

Richard I’s death in 1199 presented John with the opportunity to claim the throne. While the concept of representative succession favored Arthur, John successfully secured the crown, being invested as Duke of Normandy and crowned King of England in May 1199. Arthur, supported by Philip II, was recognized as Richard’s heir in Anjou and Maine, leading to a complex political landscape. The Treaty of Le Goulet in 1200 formally recognized John as Richard’s successor in all French possessions, but at a significant cost of financial and territorial concessions to Philip, highlighting the precariousness of John’s continental holdings.

King John of England, a portrait capturing the regal authority and the weight of the crown he bore during his reign.

The fragile peace with France soon dissolved, triggered by John’s controversial second marriage to Isabella of Angoulême in 1200. His first marriage to Isabella of Gloucester had been annulled, and his subsequent marriage to Isabella of Angoulême, who was betrothed to Hugh IX de Lusignan, provoked a rebellion by the Lusignans. They appealed to Philip II, who summoned King John to his court. John’s refusal to appear led to war. Despite an initial victory at Mirebeau in 1202, where Arthur of Brittany was captured, John ultimately lost Normandy by 1204. By 1206, Anjou, Maine, and parts of Poitou were also lost to Philip II, marking a catastrophic loss of Angevin continental territories.

These losses, rooted in French resource superiority and strain on English and Norman resources, significantly damaged King John’s prestige. The permanent shift of John’s focus to England, coupled with the death of Archbishop Hubert Walter in 1205, resulted in a more personally driven and arguably autocratic style of government. John’s determination to regain his French territories fueled ruthlessly efficient financial administration. This included heavy taxation, forest inquiries, exploitation of Jewish communities, feudal tenure investigations, and aggressive use of royal prerogatives. These measures, while effective in raising revenue, fueled resentment among the English barons and contributed to accusations of tyranny that would define his reign.

Magna Carta and Legacy

The baronial discontent, stemming from heavy taxation, military failures in France, and John’s autocratic rule, culminated in open rebellion. In 1215, the barons confronted King John and forced him to seal the Magna Carta at Runnymede. The Magna Carta, a landmark document in English legal history, aimed to limit royal power and protect certain rights of the barons. It included clauses addressing feudal dues, legal procedures, and the rights of the Church, establishing principles that would later be interpreted more broadly to encompass the rights of all Englishmen.

While King John initially sealed the Magna Carta, he quickly sought to undermine it, and Pope Innocent III declared it invalid. This led to renewed civil war, with barons inviting Prince Louis of France to invade England and replace John as king. However, King John’s sudden death in October 1216, amidst the turmoil, changed the course of events. His young son, Henry III, succeeded him, and the baronial rebellion eventually subsided.

King John’s reign is a pivotal period in English history. Despite his military failures and reputation for tyranny, the Magna Carta, born out of opposition to his rule, stands as a testament to the enduring struggle for rights and limitations on royal power. His legacy is complex – remembered for both his failures as a king and the unintended consequences of his actions that contributed to the development of constitutional government in England.

John, king of England

John, king of England

A 14th-century manuscript illustration of King John of England hunting, providing a visual glimpse into the royal life and pastimes of the era.