John Marshall Harlan (1833–1911) stands as a towering figure in the history of the U.S. Supreme Court. Initially a slaveholder and defender of the institution, Harlan underwent a profound transformation, emerging as a staunch advocate for the Union and, most notably, a powerful voice for civil rights and First Amendment freedoms. His 34-year tenure on the Court saw him become a relentless champion for the rights of minorities, often dissenting against the majority to articulate principles of equality and justice that would later shape American constitutional law. Harlan’s early advocacy for incorporating the Bill of Rights into the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause, applying these fundamental rights to state governments, became a cornerstone of 20th-century civil rights litigation and First Amendment jurisprudence. This doctrine of incorporation cemented his legacy as a visionary legal thinker.

From Whig Politics to Supreme Court Justice: Harlan’s Evolving Ideology

Born in Mercer County, Kentucky, John Marshall Harlan was named after the esteemed Chief Justice John Marshall, a namesake that foreshadowed his own significant legal career. His father, James Harlan, was a lawyer, a Whig politician, and a U.S. Congressman, instilling in his son an early exposure to law and politics. Harlan pursued his education, earning a bachelor’s degree from Centre College in Danville and spending two years at Transylvania University in Lexington. He concluded his legal studies by apprenticing in his father’s law office, a common practice at the time. Admitted to the bar in 1853, he entered the political arena as a member of the Whig Party, following in his father’s footsteps.

The disintegration of the Whig Party in the mid-1850s marked a period of significant political and philosophical evolution for Harlan. He briefly aligned with the anti-immigrant “Know Nothing” movement in 1857 before becoming a Constitutional Unionist, supporting John Bell in the pivotal 1860 presidential election. With the onset of the Civil War (1861–1865), Harlan firmly embraced the Union cause. He served in the Union Army, rising to the rank of colonel. However, he resigned his commission following his father’s death and subsequently was elected Attorney General of Kentucky, further solidifying his presence in public life.

Despite his Unionist stance during the war, Harlan’s views on slavery and racial equality were initially conservative. He publicly criticized President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation of 1863, deeming it unconstitutional. Harlan himself did not free his slaves until compelled by the Thirteenth Amendment, which abolished slavery nationwide. Furthermore, he opposed the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments, which aimed to grant citizenship rights and voting rights to formerly enslaved people. In the 1864 election, he voted for Democrat George McClellan. However, in a dramatic shift, Harlan became a Republican in 1868, signaling a change in his political allegiances.

The year 1871 witnessed a remarkable transformation in Harlan’s convictions. He underwent a profound ideological reversal, becoming a vocal supporter of the Reconstruction Amendments. In his unsuccessful campaign for Governor of Kentucky as a Republican, he openly repudiated his earlier stances on slavery and Reconstruction. His political profile rose rapidly. He was considered as a potential running mate for Ulysses S. Grant in the 1872 presidential election and played a key role in the election of Rutherford B. Hayes in 1876. Hayes, recognizing Harlan’s legal acumen and political significance, appointed him to the Supreme Court in 1877, fulfilling Harlan’s long-held ambition.

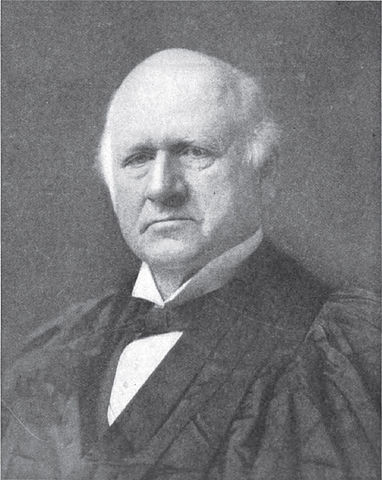

Justice John Marshall Harlan in 1907

Justice John Marshall Harlan in 1907

Justice John Marshall Harlan in 1907, showcasing his distinguished presence during his later years on the Supreme Court. Known as “The Great Dissenter,” Harlan’s dissenting opinions, often challenging the prevailing legal views of his time, have become highly influential in American constitutional history. His unwavering commitment to justice and equality, even when in the minority, solidified his legacy as a legal visionary.

The Great Dissenter: Harlan’s Landmark Dissents on Civil Rights

Justice Harlan earned the moniker “The Great Dissenter” for his frequent and powerful dissenting opinions. Of the 891 opinions he authored, 123 were dissents, many of which have become foundational texts in American constitutional law. His dissent in United States v. Harris (1883) exemplifies his commitment to federal protection of civil rights. In this case, the Court ruled that the federal government lacked the power to prosecute individuals for lynching black prisoners, arguing that the Fourteenth Amendment only applied to state action, not private actions. Harlan, in sole dissent, argued that the federal government did have the authority to protect individuals from such violence, underscoring his expansive view of federal power to safeguard civil rights.

Later in 1883, Harlan penned another significant dissent in the Civil Rights Cases, a consolidation of five cases challenging the Civil Rights Act of 1875. This Act prohibited discrimination based on race in public accommodations and transportation. The Court, in an 8-1 decision, struck down key provisions of the Act, again asserting that the Fourteenth Amendment only restricted state-sponsored discrimination, not private acts of discrimination by individuals and businesses.

Harlan vehemently disagreed. Echoing Radical Republican ideals, he argued that the formerly enslaved were not seeking special privileges but rather equal treatment. He powerfully asserted that allowing private discrimination created a “badge of slavery,” branding an entire minority group as inferior, directly violating the spirit and intent of the Reconstruction Amendments. He believed the Court’s narrow interpretation undermined the very purpose of these amendments, which were designed to secure genuine equality for Black Americans.

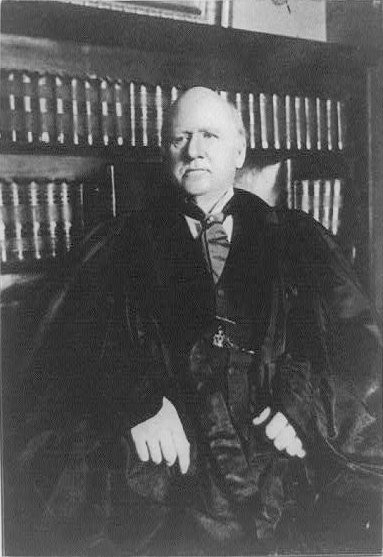

John Marshall Harlan's most famous dissent was in the landmark “separate but equal” segregation case, Plessy v. Ferguson (1896).

John Marshall Harlan's most famous dissent was in the landmark “separate but equal” segregation case, Plessy v. Ferguson (1896).

A portrait of John Marshall Harlan, capturing his thoughtful and resolute demeanor. His most celebrated dissent came in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the infamous “separate but equal” case. Harlan’s courageous stance against racial segregation, arguing for a color-blind Constitution, highlighted his profound commitment to equality and justice under the law.

Plessy v. Ferguson and the Color-Blind Constitution

Harlan’s most renowned dissent came in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), the case that cemented the “separate but equal” doctrine of racial segregation. The Court, in a 7-1 decision, upheld a Louisiana law mandating racial segregation on railway cars, arguing that segregation was permissible as long as facilities were equal.

In his dissenting opinion, Harlan delivered an impassioned and prophetic argument. He declared, “Our Constitution is color-blind,” famously stating that “in this country there is no superior, dominant ruling class of citizens.” He condemned the notion that states could regulate civil rights based solely on race, foreseeing that the decision would sow the “seeds of race hate” into American law. Harlan’s dissent was largely disregarded at the time, but it became a rallying cry for the Civil Rights Movement in the 20th century.

Despite his powerful dissent, the Plessy decision entrenched racial segregation for decades, shaping American society until the Court finally overturned it in Brown v. Board of Education (1954). Harlan also dissented alone in Berea College v. Kentucky (1908), where the Court upheld a state law enforcing segregation even against a private, integrated college.

Interestingly, Harlan did join the majority in cases like Reynolds v. United States (1879) and Davis v. Beason (1890), which upheld laws against polygamy in U.S. territories. In these instances, the Court ruled that religious freedom under the First Amendment did not extend to practices deemed illegal and against public morals, demonstrating the complexities of balancing individual rights and societal norms in constitutional law.

John Marshall Harlan’s legacy extends far beyond his lifetime. His dissenting opinions, initially in the minority, became foundational principles of American civil rights law. His unwavering commitment to equality, his vision of a color-blind Constitution, and his powerful dissents against racial injustice have cemented his place as “The Great Dissenter” and a true champion of American justice.

This article was originally published in 2009. James R. Belpedio was a Professor of History at Becker College.