The epic saga of Shōgun, brought to life once again in the recent FX series, has captivated audiences with its portrayal of feudal Japan and the compelling character of John Blackthorne. Played by Cosmo Jarvis, Blackthorne is depicted as an English navigator who, through a twist of fate, lands in Japan in 1600 and becomes entangled in the nation’s turbulent political landscape. As viewers are drawn into his journey, a natural question arises: is John Blackthorne a purely fictional creation, or is he rooted in historical reality?

Cosmo Jarvis as John Blackthorne in FX

Cosmo Jarvis as John Blackthorne in FX

Cosmo Jarvis embodies John Blackthorne in FX’s Shōgun, a character inspired by the historical figure of William Adams (Image courtesy of Disney+)

While the dramatic plot of Shōgun is a work of fiction, the character of John Blackthorne is indeed inspired by a real historical figure: William Adams. Adams was not just an Englishman who reached Japan; he was the first Englishman to ever set foot on Japanese soil and remarkably, he rose to become a trusted advisor to one of Japan’s most powerful leaders, earning him a place in history as a Western samurai, albeit not a warrior in the traditional sense.

William Adams: The Man Behind the Myth of John Blackthorne

The parallels between John Blackthorne and William Adams extend beyond mere inspiration. Just as Blackthorne forges a crucial alliance with Lord Yoshii Toranaga (Hiroyuki Sanada) in Shōgun, Adams developed a close and influential relationship with the historical figure who served as the model for Toranaga: Tokugawa Ieyasu. Tokugawa Ieyasu, a shrewd and ambitious warlord, would eventually become shōgun, the supreme military ruler of Japan. Adams’s expertise in navigation, shipbuilding, and international affairs proved invaluable to Ieyasu, leading to Adams becoming a key diplomatic and trade advisor. Ieyasu bestowed upon Adams significant honors, including land, the prestigious title of hatamoto (a high-ranking retainer), and even a pair of swords, symbols of samurai status, recognizing his unique contributions to the shogunate.

The Early Life of William Adams: From Kent to the Seas

William Adams’s journey to becoming Miura Anjin, the “Pilot of Miura,” began far from the shores of Japan. Born in Gillingham, Kent, in September 1564, Adams’s early life remains somewhat shrouded in mystery. Much of what we know about his formative years comes from a letter he penned in 1611 from Hirado, Japan, addressed to his “Unknown friends and countrymen.” This letter provides invaluable insights into his experiences and perspective.

At the young age of twelve, Adams embarked on a path that would shape his destiny, becoming an apprentice to Nicholas Diggins, a shipbuilder in Limehouse, London. Here, he immersed himself in the world of nautical navigation, astronomy, and shipbuilding – skills that would later prove crucial in his adventures. He dedicated twelve years to this apprenticeship, a period that coincided with a pivotal moment in English history: the Spanish Armada of 1588.

In 1588, at the age of 24, Adams answered the call of duty and joined Francis Drake’s navy, enlisting aboard the supply ship Richard Duffylde. While his direct involvement in the battles against the Armada remains uncertain, this experience undoubtedly exposed him to the realities of naval warfare and further honed his maritime skills. Following England’s victory and the disbandment of the Queen’s fleet, Adams sought new opportunities. He spent a decade working with the Barbary Company merchants, gaining experience in trade and expanding his horizons beyond England. However, it was the lure of the East and the burgeoning Dutch maritime power that would ultimately set him on the path to Japan.

Venturing East: From Dutch Service to the Shores of Japan

The late 16th century was a period of intense global exploration and competition, particularly between European powers vying for control of lucrative Asian trade routes. The Dutch, locked in a protracted war with Spain, were determined to break the Spanish and Portuguese monopoly on Asian goods. When King Philip II of Spain inherited the Portuguese throne in 1581, effectively closing Lisbon – a key trading hub for Dutch merchants – the Dutch were compelled to seek direct access to Asian markets. This geopolitical backdrop created an alliance of convenience between Dutch and English sailors against their common Spanish and Portuguese rivals.

In 1598, William Adams entered the service of the Dutch, signing on as a pilot – a master navigator – for a fleet of five ships embarking on a daring expedition to the East Indies. This voyage was fraught with peril and hardship from the outset.

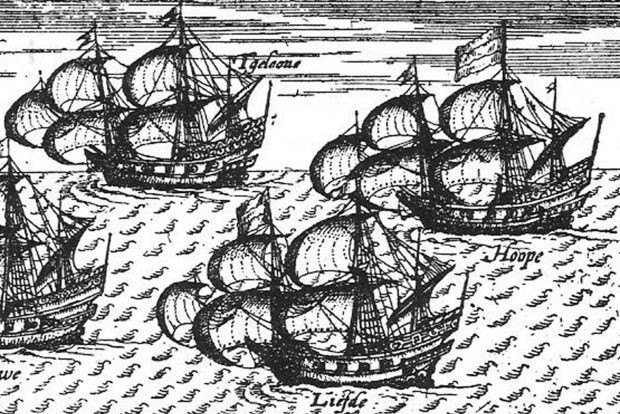

Illustration of Dutch ships

Illustration of Dutch ships

The Liefde, pictured among other Dutch vessels, was the sole ship from the original five to successfully reach Japan in 1600, carrying William Adams to his destiny (Photo by Getty)

The ambitious plan was to navigate through the treacherous Strait of Magellan, raid Spanish ships and settlements along the South American coast, and then utilize the spoils to trade for valuable goods in Asia, returning to Europe via the same arduous route. However, as Frederik Cryns, a leading expert on William Adams and historical consultant for FX’s Shōgun, explains, “That was the plan, and it didn’t work out how they wanted it to.”

Speaking on the HistoryExtra podcast, Cryns detailed the catastrophic journey: “They had a lot of problem with first the winds, so they couldn’t proceed on schedule. They didn’t have enough food, so a lot of the sailors starved. They had diseases and they had to fight the Portuguese, then they had to fight the Spanish. And when they came into South America, they were attacked by the native peoples living there.” Among the casualties in these South American encounters was Adams’s own brother, Thomas.

Out of the initial five ships, only one, the Liefde (meaning “Love” in Dutch), completed the grueling voyage to Japan, arriving in April 1600, nearly two years after departing Rotterdam. Of the original crew of over a hundred men aboard the Liefde, only a score survived, emaciated and weakened by disease. William Adams was among these survivors, unknowingly stepping onto the stage of his remarkable destiny.

Encountering Japan and Tokugawa Ieyasu: From Prisoner to Advisor

The arrival of the Liefde in Japan was met with suspicion and intrigue. Wary Japanese locals and Portuguese Jesuit priests, who had until then maintained a near-exclusive European presence in Japan, greeted the newcomers. The Portuguese, eager to preserve their influence, wasted no time in attempting to portray the Dutch crew as pirates, hoping to incite the Japanese authorities to execute them.

However, news of the arrival of this unusual ship and its even more unusual crew reached the ears of Tokugawa Ieyasu, one of Japan’s most powerful daimyo (feudal lords) and a key member of the Council of Regents ruling in place of the young heir to the Toyotomi clan. Ieyasu, a man of keen intellect and strategic vision, saw an opportunity where others saw only threat. He ordered the crew to be brought to him in Osaka, initiating a series of events that would irrevocably alter William Adams’s life and influence the course of Japanese history.

Contrary to the dramatic narrative in Shōgun, William Adams did not play a direct role in Tokugawa Ieyasu’s rise to power during the pivotal Battle of Sekigahara in October 1600. As Cryns notes, Adams’s involvement in these events is minimal. After being interrogated by Ieyasu and briefly imprisoned, Adams was released and relocated to Uraga, near Edo (modern-day Tokyo), along with his ship and remaining crew. While denied permission to repair the Liefde and return to Europe, Adams was otherwise left unmolested.

“He’s just sitting idle while Ieyasu fights his final battle against Ishida Mitsunari at Sekigahara,” Cryns explains. “It’s only after Ieyasu establishes his rule and everything stabilises that Adams is asked to join him.” It was after Ieyasu solidified his position as the dominant power in Japan that he recognized the true value of William Adams’s knowledge and skills. Adams was summoned to Ieyasu’s court, marking the beginning of his transformation from a stranded pilot to a trusted advisor.

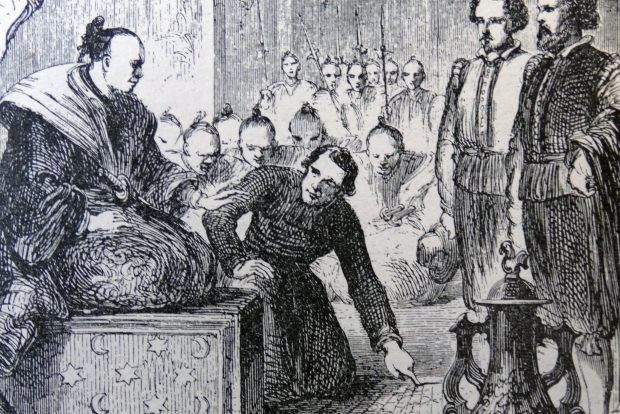

William Adams is brought before Japanese shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu

William Adams is brought before Japanese shōgun Tokugawa Ieyasu

William Adams stands before Tokugawa Ieyasu, an encounter that would lead to a remarkable relationship and Adams becoming one of the shōgun’s most trusted confidants (Photo by Getty)

Advisor to the Shōgun: Shaping Japan’s Global Relations

While Shōgun exaggerates Blackthorne’s direct impact on Toranaga’s victory, the series accurately portrays the profound influence William Adams wielded as an advisor to Tokugawa Ieyasu. Adams became a crucial bridge between Japan and the West, shaping the nation’s foreign policy and trade relationships.

Even after Sekigahara, Ieyasu faced internal challenges in consolidating his rule, not fully quelling all opposition until 1615. Externally, he sought to break the Portuguese monopoly on foreign trade, particularly their control of vital commodities like Chinese silks and lead. Recognizing Adams’s expertise, Ieyasu relocated him to Edo in 1603 and frequently sought his counsel.

One of Ieyasu’s key requests was for Adams to build Western-style ships. Adams, leveraging his shipbuilding knowledge and collaborating with Japanese craftsmen, constructed an 80-tonne vessel, introducing Western shipbuilding techniques to Japan. Impressed by Adams’s capabilities, Ieyasu commissioned a larger, 120-tonne ship. These ships were instrumental in Ieyasu’s ambitions to establish Japanese trade expeditions throughout Asia.

In recognition of his invaluable service, Ieyasu bestowed upon Adams significant rewards. He granted him an estate on the Miura peninsula, elevated him to the rank of hatamoto, and bestowed upon him the Japanese name Miura Anjin, meaning “Pilot of Miura.” This elevated status brought with it increased income and a retinue of households to serve him, effectively making Adams a minor lord within Japan.

Adams played a pivotal role in opening Japan to trade with the Dutch and English. Though forbidden from leaving Japan himself, he facilitated the arrival of Dutch traders in 1609 and English traders in 1613. He became Ieyasu’s official interpreter, central to establishing an English trading factory in Japan.

Perhaps Adams’s most consequential advice came in 1611, when the Spanish sought to establish trade relations, offering favorable terms on the condition that Ieyasu sever ties with the Dutch. While Ieyasu refused this condition and allowed the Spanish to trade and establish missions, he also granted them permission to survey Edo Bay. Adams, deeply suspicious of Spanish intentions, cautioned Ieyasu that this survey was likely a prelude to a potential invasion.

Cryns highlights the significance of Adams’s warning: “Adams says, you have to be aware because they send missionaries, they will make a lot of Christians in Japan, and then together they cooperate with those Christians to overthrow your government.” This warning resonated deeply with Ieyasu, contributing to a growing distrust of Christian missionary activities and ultimately leading to the suppression of Christianity in Japan and the subsequent isolationist policies that would define Japan for centuries. Adams’s insights into European power dynamics and the potential threat posed by religious and colonial expansion had a profound and lasting impact on Japan’s future.

Miura Anjin: The Pilot’s Japanese Name

In Shōgun, John Blackthorne is often addressed as “Anjin,” reflecting the Japanese difficulty in pronouncing his English name. “Anjin” is simply the Japanese word for pilot or navigator. Similarly, William Adams, upon receiving his estate on the Miura peninsula, became known as Miura Anjin, solidifying his identity within Japanese society and acknowledging his profession.

The End of a Remarkable Life: William Adams’s Death

William Adams lived out his days in Japan, passing away on May 16, 1620, four years after the death of his patron, Tokugawa Ieyasu. He left behind a complex personal life, with a wife and children in England and a Japanese wife and children in Japan.

Japan as a Final Destination: Adams’s Choice

While the novel Shōgun concludes with Toranaga declaring that it was Blackthorne’s karma to never leave Japan, the reality for William Adams was slightly different. While he never returned to England, it wasn’t due to forced confinement. In 1613, Ieyasu granted Adams permission to leave Japan permanently. However, when offered passage on an English ship bound for home, Adams declined.

Instead, he chose to remain in Japan, taking a position with the British East India Company and continuing to engage in maritime ventures in Asia, navigating expeditions to Siam (Thailand) and Vietnam. As Cryns suggests, Adams likely recognized the unique position and influence he had attained in Japan: “In Japan he was a small lord. He had a fief allotted to him by Ieyasu. He had households serving him…He was a man of influence in Japan. But if he went back to England, he was just another sailor.” William Adams chose to embrace his life as Miura Anjin, a figure of significance in Japan, rather than return to a more ordinary existence in England.

Shōgun offers a compelling, albeit fictionalized, glimpse into a fascinating historical period and the life of a remarkable individual. The character of John Blackthorne, while a creation of James Clavell’s imagination, is firmly rooted in the extraordinary true story of William Adams, the English navigator who became a samurai advisor and left an indelible mark on the history of Japan and its relationship with the wider world.

To delve deeper into this captivating era, Shōgun is available to stream on Disney+. For further exploration of historical themes, consider checking out curated lists of historical movies and TV shows.

Frederik Cryns’s book, In the Service of the Shogun: The Real Story of William Adams, provides an in-depth account of Adams’s life and will be available in May 2024 from Reaktion Books.