Perfectionism, a relentless pursuit of flawlessness, can be a crippling force in our lives. To understand its insidious nature, we can delve into the intricate world-building of John Wick. If you’re unfamiliar with the series, a quick online search will provide the necessary context for this exploration. In a previous discussion, we ventured into The Continental’s bar to confront our inner critic. Now, let’s turn our attention to another compelling aspect of the John Wick universe: the ballerina from John Wick 3.

This blog post will focus on the striking scene featuring a ballerina, a moment that vividly illustrates the damaging effects of perfectionism.

You might recall the scene where a ballerina repeatedly falls as John Wick approaches The Director to redeem his “ticket.” The Director’s insistence on flawless pirouettes, despite the ballerina’s obvious exhaustion and pain, is a powerful depiction of unattainable standards. This scene immediately brings to mind the thought: “perfection is the standard.” It prompts reflection: Did we internalize this demanding standard during formative experiences? How many times was this message reinforced by authority figures, like The Director, or societal structures, like the Ruska Roma? And most importantly, how does this ingrained perfectionism hinder us from pursuing our deepest aspirations?

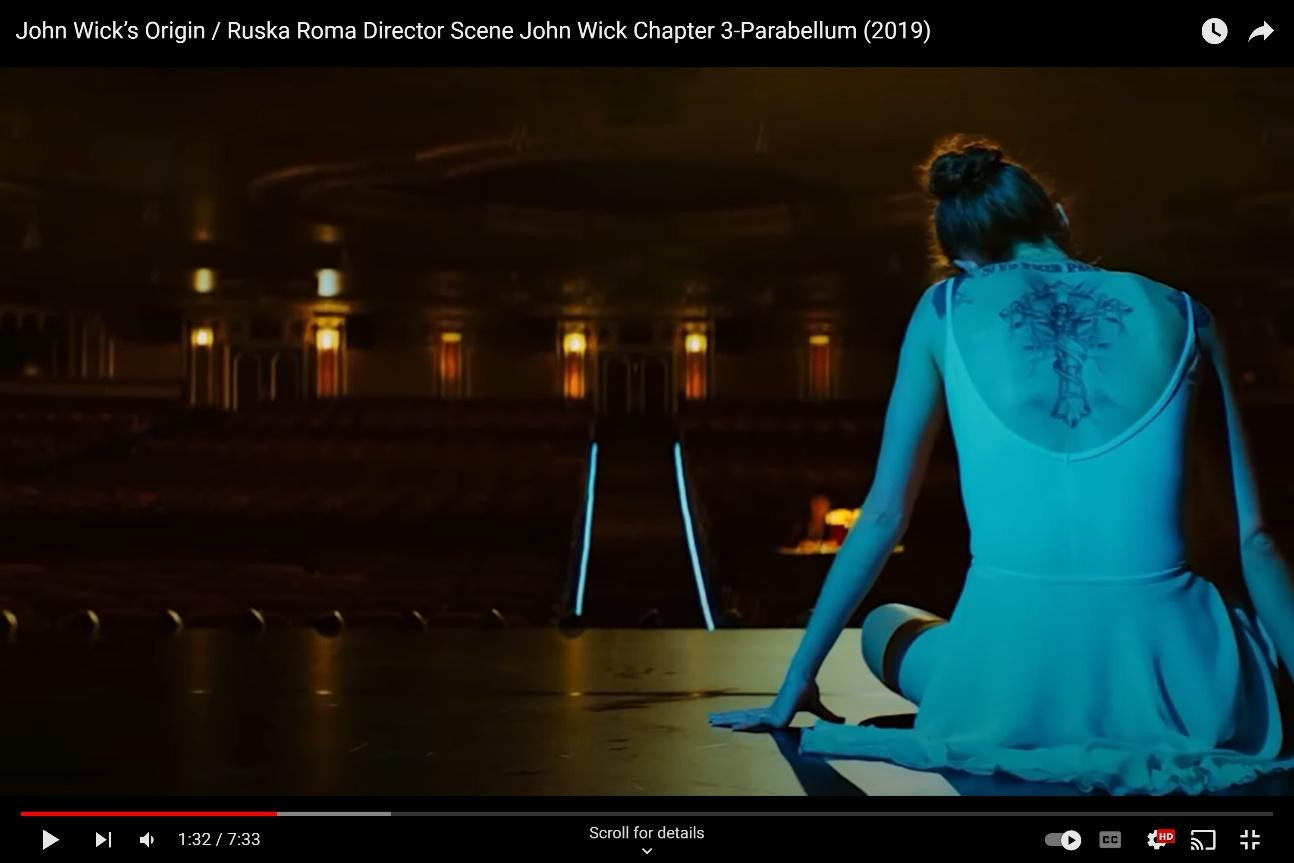

Unity Phelan embodying a Ruska Roma ballerina in a scene from John Wick: Chapter 3 – Parabellum, directed by Chad Stahelski. This image captures the dedication and discipline associated with ballet and the John Wick universe.

Let’s explore this further through a creative scene, stepping into the ballerina’s perspective.

My sister and I find ourselves at the Rome Continental bar. The shattered glass in the lobby is a clear sign – someone dared to conduct illicit business on Continental grounds. A shiver runs down my spine as I vaguely wonder who it was. Given the chaos that ensued the last time this happened in New York, my jaw clenches. An Adjudicator’s arrival is usually imminent after such a transgression.

We order two limoncellos, served in delicate vintage glasses etched with floral designs. Lost in admiring the daisy yellow hue flickering across the glass’s intricate lines, my sister’s voice breaks through, “How was work tonight?”

I grimace, my gaze fixed on the glass. “Not good.”

Our paths of “work” diverge significantly. My sister remains The Director’s favored protégé. From our earliest days at the Ruska Roma, her affinity for ballet was evident. For her, the grueling training was not mere punishment, but a profound mode of self-expression. She channeled unimaginable agony into every graceful movement, consistently earning center stage in The Director’s ballets. If art truly stems from pain, as The Director incessantly proclaimed, then my sister’s performances were the epitome of Ruska Roma suffering. I envy her position as Principal Dancer. Compared to her, I am mere trash, perpetually failing.

I vividly recall Mr. Wick’s arrival to redeem his ticket. I couldn’t execute a pirouette to the required standard, collapsing repeatedly. The humiliation and physical pain intensified with each fall, exacerbated by failing in front of him – the man whispered to be feared even by shadows. As he knelt before The Director, I slumped, overwhelmed by the realization of my inadequacy. I could never match my sister’s brilliance. Even if performance wasn’t the true measure… I was not enough. And the crushing certainty that I never would be settled deep within me. They wouldn’t keep me here. The Director’s relentless demand for perfection from us all was an insurmountable barrier for me.

My sister’s slender hand gently rests on my wrist, the slight pressure pulling me from my spiraling thoughts. I meet her gaze.

She studies me intently, her eyes searching. “You will find your place. Tonight was just your first assignment. Let’s see how things unfold before we face her judgment.”

A subtle release eases the tension in my chest. She’s right. It was only the first night. Some tasks require months, even years.

We lapse into comfortable silence as the bartender slides a small silver tray towards me. My eyes widen, fixated on the elegant cream envelope sealed with deep cherry wax. My chest tightens. The insignia imprinted in the wax is unmistakable. They already know how tonight went. I recognize the sender. Why did I even bother trying?

A quick scan of the room reveals other patrons lounging on chaise lounges and Chesterfield sofas, oblivious. The bartender continues polishing crystal glasses at the bar’s end. No one has noticed. My sister’s reassuring hand returns to my wrist. “Don’t. I’m sure it’s fine. We are on Continental grounds. Finish your drink, and then we will address it.”

The tension becomes unbearable, and I grip my limoncello glass so tightly it shatters in my hand.

///END SCENE///

This scene illuminates several critical aspects of perfectionism:

-

Unrealistic Self-Measurement: Perfectionism compels us to hold ourselves to unattainable standards of self-evaluation.

“I envy her position as a Principal in the Director’s ballet. I am untalented trash by comparison. Always failing.” -

External Validation Dependence: These self-imposed metrics are often dictated by external authorities (The Director, the Ruska Roma) and voices, overshadowing our own internal compass.

“The Director demanded nothing short of perfection from all of us. I was incapable of reaching it.” -

Internalized Inadequacy: We internalize these external metrics as irrefutable truths about our own worth.

“Even if good wasn’t a measure of performance… I was not enough. Worse yet… I never would be.” -

Comparative Self-Destruction: We reinforce this lack of self-worth by constantly comparing ourselves to others we perceive as meeting these external standards.

“While he knelt before The Director, I slumped, knowing I was never going to be good enough… I couldn’t even be as good as my sister.” -

Self-Perpetuating Cycle of Failure: Our inner voice and self-belief erode. We become trapped in a cycle of self-doubt and inaction, hindering growth and progress.

“I don’t know why I bothered to even try.”

The ballerina on stage, embodying vulnerability and resilience amidst pressure.

The ballerina on stage, embodying vulnerability and resilience amidst pressure.

Why is addressing perfectionism crucial?

Perfectionism acts as a roadblock, halting us before we even begin. It whispers, “Don’t even attempt it unless you’re certain it will be extraordinary. Otherwise, what’s the point?”

This mindset is detrimental, especially for creatives. Initial creations are rarely masterpieces. Years of practice and refinement are often necessary before we develop a clear vision of “good” in our own artistic voice. Even outside creative fields, perfectionism prevents us from seizing opportunities, trapping us in a perpetual state of “what ifs.”

Perfectionism is a learned behavior, passed down through generations as a coping mechanism rooted in scarcity and fear – fear of loss, fear of rejection, relational scarcity, economic instability. In environments where error is not tolerated and survival hinges on flawless execution, perfectionism thrives.

When perfectionism dictates our decisions, we become hyper-aware of potential pitfalls and reasons why we are inadequate for opportunities. When our inner critic is fueled by perfectionism, rather than compassion, we limit our potential.

The antidote to perfectionism: desire your dreams intensely enough to pursue them imperfectly.

How does “not enough” evolve into “good enough”?

Our work becomes “good enough” when we embrace our own inherent worthiness.

This shift occurs when we decide to seek validation internally, rather than externally.

I vividly recall wrestling with this during the creation of my debut picture book, The Krewe of Barkus and Meoux. Fear consumed me – fear of writing it incorrectly, fear of inadequate artwork. I was terrified that any imperfection would jeopardize my creative career aspirations. However, a pivotal moment arrived during the writing process when I realized my desire to create outweighed my fear of imperfection.

I recognized my profound love for illustration and writing. Even if “terrible” was the price of entry, I was willing to embrace imperfection for the sheer joy of the creative journey.

Perfectionism stems from the deep-seated fear of inadequacy – the fear that our creative expressions, our inner worlds made tangible, will expose our perceived deficiencies to judgment.

Perfectionism places fear in the driver’s seat of our lives, causing us to swerve erratically and discard potential masterpieces along the way, leaving behind a landscape littered with “could haves.”

You could have pursued that field of study. You could have created that painting. You could have written that book. You could have tried out for that team. You could have applied to that university. You could have nurtured that friendship. You could have explored that passion that once ignited your soul. You could have pursued that dream job, that promotion, or that _________ (fill in your blank).

Knowing you attempted is infinitely more valuable than never trying at all.

The choice rests with you:

Either you confront and dismiss that fear, reclaiming control of your path, or you passively surrender to its dictates.

Get to work. Embrace the process.

A perfectionistic approach undermines creative endeavors. No creative work exists in isolation. It is part of an ongoing dialogue with the work that preceded it and the work yet to come. The complete narrative emerges from the entire body of work, not a single piece. This understanding liberates us from the pressure of initial perfection. The true value lies in the growth and journey, not the elusive pursuit of a singular masterpiece.

We must shift our mindset to prioritize “good enough” and grant ourselves permission to iterate and evolve. Even as I write this, my inner critic protests the mediocrity of “good enough” (but my inner champion, as discussed previously, quickly silences her). Ultimately, you define “good enough.” I can choose to approach my work from a place of fear and scarcity, obsessing over every detail in a futile pursuit of perfection. Or, I can adopt a professional approach, embracing self-trust and abundance. Each day, I consciously choose professionalism (iterative and evolving) over perfectionism (fatalistic and final). This transformation is only possible when we abandon scarcity and commit to action – Get TO WORK.

It’s not about opportunities seeking you out because you are “good enough”; it’s about you recognizing opportunities as “good enough” for your growth and journey.

You, and only you, set the standards for your work.

Let your efforts be directed by progress, not perfection.

Who instilled the belief that you must be perfect? Perform flawlessly? Create immaculate work? When did you begin to accept this narrative? When perfection becomes the standard, exploration and growth are stifled. Instead, you become trapped in a cycle of inadequacy before you even start. The key is to simply begin. You have the choice to approach yourself and your work with compassion, or to relentlessly criticize yourself for falling short of an unattainable standard – likely one that wasn’t even your own. The choice is yours.

Remember, what is meant for you will find you, even if it’s not perfect from the outset.