John Denver, a name synonymous with the soaring melodies of folk and country music, left an indelible mark on the American music landscape. While December 31st would have marked his 70th birthday had he lived beyond the tragic 1997 accident, his music continues to resonate with audiences worldwide. Although the peak of his popularity in the 1970s may seem distant to younger generations, John Denver’s musical legacy, particularly songs like “Leaving on a Jet Plane,” endures. His earnest performances and genuine passion for both music and environmental causes, captured in concert videos and recordings, still hold a unique charm. Denver was a gifted songwriter and performer, crafting songs within the folk idiom with remarkable skill. While he might not have always received the critical acclaim bestowed upon some of his contemporaries, a closer look at his work, especially “Leaving on a Jet Plane,” reveals a depth and sophistication often overlooked.

One of the key aspects often missed in discussions about John Denver is the breadth of his songwriting. Beyond the cheerful anthems celebrating nature and love, a vein of melancholy and introspection runs through much of his music. Songs like “Eclipse” and “Fly Away” hint at urban alienation and a deeper sadness. Themes of loneliness, isolation, and the potential failure of romantic dreams are recurring motifs in his work, adding layers of complexity to his outwardly optimistic persona. This duality is strikingly evident when examining the evolution of “Leaving on a Jet Plane,” one of his earliest compositions.

Interestingly, John Denver’s initial forays into professional songwriting reveal these contrasting facets of his musical personality. His very first copyrighted song, penned under his birth name “H.J. Deutschendorf, Jr.” and titled “For Bobbie,” appeared on The Mitchell Trio’s second album in 1965, during his tenure as a member. While a studio recording from that era is elusive on platforms like YouTube, a 1987 reunion performance with original Mitchell Trio members Mike Kobluk and Joe Frazier offers a glimpse into the song’s original form, closely mirroring the ’65 studio version.

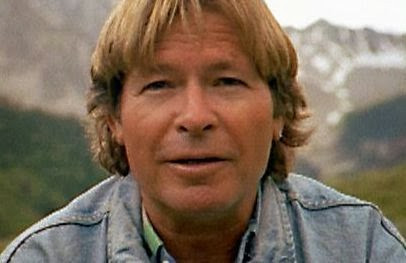

John Denver performing with the Chad Mitchell Trio, showcasing his early folk roots.

Peter, Paul and Mary famously covered “For Bobbie,” retitling it “For Baby” and transforming it into a lullaby-esque song for a newborn. However, Denver continued to perform and record the song as “For Bobbie,” maintaining its original title and lyrical intent as a straightforward, albeit simple, love ballad. While pleasant, “For Bobbie” suggests a competent but not yet fully formed songwriting talent. Had Denver’s career trajectory solely relied on songs of this nature, his path might have taken a very different turn.

Fortunately, John Denver possessed a far greater songwriting aptitude, which became strikingly apparent in his subsequent work. In 1966, he penned a song initially titled “Babe, I Hate To Go.” However, Milt Okun, a prominent producer, deemed the title uninspired. Okun proposed using the opening line of the chorus as the title instead of the closing line, and thus, “Leaving, On A Jet Plane” was born. The Mitchell Trio’s final iteration, featuring Kobluk and David Boise, recorded “Jet Plane” – complete with the comma in the title, which has since been dropped but remains in the copyright – for their 1967 farewell album, Alive.

Both the melody and lyrics of “Leaving on a Jet Plane” represent a significant leap forward in Denver’s songwriting compared to “For Bobbie.” However, this early Mitchell Trio rendition feels somewhat hurried, as if the full emotional weight of the song hadn’t yet been realized. Despite the lyrics depicting lovers parting, with a hopeful yet poignant mention of a “wedding ring” in the third verse, the performance lacks the reflective depth that would later become a hallmark of Denver’s solo interpretations. Denver’s initial solo recording, featured on his 1969 debut album Rhymes and Reasons, exhibits a similar tempo and pacing, though with a slightly more contemplative reading of the lyrics.

It was not until years later, when Denver revisited some of his early compositions for his monumental John Denver’s Greatest Hits album, a nine-times platinum success, that “Leaving on a Jet Plane” truly found its definitive form. In this later recording, Denver slowed down the tempo and adopted a more subdued and introspective vocal delivery, capturing the song’s inherent sadness and vulnerability with greater nuance. This refined interpretation became the standard version that Denver performed in concert throughout the remainder of his career, solidifying its status as a deeply moving and emotionally resonant ballad.

Despite the inherent quality of “Leaving, On A Jet Plane,” both the song and John Denver’s career teetered on the brink of obscurity in their initial phases. Sales of the early recordings were minimal, and widespread recognition remained elusive. Milt Okun, who also served as musical director for Peter, Paul and Mary, played a pivotal role in changing this trajectory. Peter, Paul and Mary, remarkably, maintained their popularity even amidst the British Invasion led by The Beatles in 1964. Okun introduced “Jet Plane” to Peter, Paul and Mary, who included it on their 1967 album Album 1700, widely considered one of their finest works. However, Warner Brothers, their label, surprisingly waited until 1969 to release it as a single. This single became Peter, Paul and Mary’s last charting hit, and notably, their only song to reach the coveted #1 position on the Billboard Hot 100 chart.

“Leaving on a Jet Plane” became particularly associated with Mary Travers, whose evocative vocals on the Peter, Paul and Mary version imbued the song with a profound sense of longing and farewell. She continued to perform and record it both with the trio and as a solo artist. The song’s inclusion on the successful 1700 album played a crucial role in propelling John Denver into the spotlight. It enabled Okun and Denver’s management to effectively market the then-unknown singer-songwriter to RCA Records, a major label. Coincidentally, John Denver’s Rhymes and Reasons debut album was released in the fall of 1969, precisely when Peter, Paul and Mary’s “Jet Plane” was climbing the singles charts. Adding to this momentum, one of Denver’s early network television appearances featured him joining Peter, Paul and Mary to perform “Jet Plane” on one of their specials in 1969, coinciding with the song’s peak popularity and marking the nascent stages of Denver’s own rise to fame.

The enduring appeal of “Leaving on a Jet Plane” is evidenced by its countless covers across diverse musical genres. From easy listening to punk rock, the song has been reinterpreted in myriad ways. Consider the Ray Conniff Singers’ rendition, a testament to the song’s melodic accessibility, or the punk rock band Me First and the Gimme Gimmes’ surprisingly energetic take, showcasing its adaptability.

Even hip-hop has embraced “Leaving on a Jet Plane,” as seen in Mos Def’s sampling of the song. While not a direct cover, it cleverly incorporates the song’s essence into a new musical context, highlighting the melody’s hypnotic quality, as Lindsay Buckingham of Fleetwood Mac described the essence of a good pop recording.

Perhaps due in part to Mary Travers’ iconic vocal performance, “Jet Plane” has become a favorite for female vocalists. Chantal Kreviazuk’s jazz-infused version for the Armageddon movie soundtrack in 1998 brought the song to a new generation, demonstrating its timeless appeal. Kreviazuk’s rendition, with its sophisticated chord structure, offers a distinct contrast to Denver’s folk origins, yet retains the song’s emotional core.

For a contemporary female interpretation, Vienna Teng’s version stands out. Teng, a Stanford engineering graduate turned introspective singer-songwriter, delivers a particularly sensitive and nuanced rendition. Her performance, notably on The David Letterman Show, reveals a deep understanding of Denver’s lyrics and avoids the vocal affectations common among many contemporary singers, emphasizing the song’s emotional depth.

F. Scott Fitzgerald famously wrote, “There are no second acts in American lives,” but revivals and reinterpretations are certainly possible, especially in music. John Denver’s career, while stratospheric, might be viewed as lacking distinct acts, instead representing a continuous ascent followed by a decline. He relentlessly pursued his entertainment projects and environmental advocacy without a significant period of reinvention. He honed his craft, becoming increasingly proficient at what he already did well. As his personal life grew more complex, a darker hue emerged in his later compositions. This isn’t a criticism, but an observation. Having created a song as universally resonant as “Leaving, On A Jet Plane,” capturing both light and shadow, it’s understandable that Denver would continue to explore similar emotional landscapes. While he may not have replicated its singular impact, his continued effort reflects his artistic commitment. “Leaving on a Jet Plane” remains a testament to John Denver’s songwriting prowess, a song that continues to resonate across generations, exploring the bittersweet emotions of departure and the enduring human experience of longing.