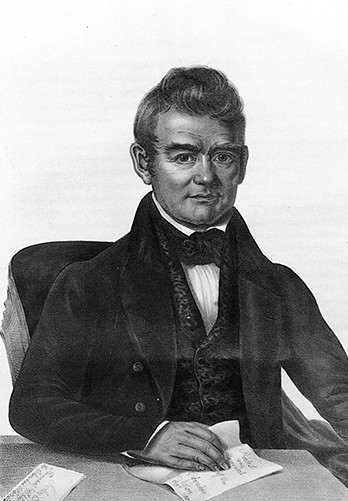

John Ross, a pivotal figure in Cherokee history, served as the Principal Chief of the Cherokee Nation for nearly four decades, navigating the tribe through some of its most challenging periods. His leadership is most notably defined by his unwavering stance during the 1830s debates surrounding Cherokee removal to Indian Territory, now present-day Oklahoma. As a staunch advocate against relocation, John Ross dedicated himself to upholding treaties that guaranteed the Cherokee people their ancestral lands.

Despite his tireless efforts in Washington, D.C., and the support he garnered, Ross and the anti-removal faction ultimately faced insurmountable opposition. The combined forces of President Andrew Jackson’s administration, neighboring state governments eager for land expansion, and the relentless westward push of American settlers proved too powerful. Adding to these external pressures, internal Cherokee divisions emerged with the pro-removal Ridge faction, who controversially signed a removal treaty, sealing the fate of the nation. Following intense internal conflict, sometimes violent, John Ross led the Cherokee people on the tragic forced migration from their southeastern homelands to the new Cherokee Nation in Indian Territory, establishing their capital at Tahlequah. This devastating journey, known as the Trail of Tears, resulted in the death of an estimated quarter of the twenty thousand Cherokee individuals.

The life of John Ross Cherokee chief was again thrust into the national spotlight during the American Civil War in the 1860s. He skillfully guided the Cherokee Nation through the complex issue of allegiance in the conflict. Although he reluctantly agreed to an alliance with the Confederacy, when Union forces invaded Indian Territory, Ross did not remain. He spent a significant portion of the war in Washington, D.C., advocating for Cherokee interests. At the war’s conclusion, he briefly returned home before going back to the capital to continue championing the Cherokee cause. John Ross passed away in Washington in 1866. His remains were returned to Tahlequah and laid to rest in his family’s burial plot.

John Ross had two marriages, first to Quatie, a Cherokee woman with whom he had five children, and after her passing, to Mary Brian Stapler, a Delaware Quaker, with whom he had two more children. While not deeply devout, he became a member of the Methodist Church. Like many of his time, he owned slaves until the Civil War. A successful merchant and plantation owner, Ross experienced financial prosperity but was also subjected to significant losses due to governmental policies and the turbulent times. His legacy is one of resilience and leadership amidst adversity. Despite the forced removal, the Cherokee people under John Ross rebuilt their nation in Indian Territory, becoming a thriving community by mid-19th century. Even through the divisions of the Civil War, the Cherokee Nation, in Ross’s final years, saw the restoration of their sovereignty.

Gary E. Moulton

Further Reading:

- Anderson, William L., ed. Cherokee Removal: Before and After. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1991.

- McLoughlin, William G. Cherokee Renascence in the New Republic. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1985.

- Moulton, Gary E. John Ross, Cherokee Chief. Athens: University of Georgia Press, 1978.

- Moulton, Gary E., ed. The Papers of Chief John Ross, 2 vols. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1985.

- Wilkins, Thurman. Cherokee Tragedy: The Ridge Family and the Decimation of a People. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press, 1986.