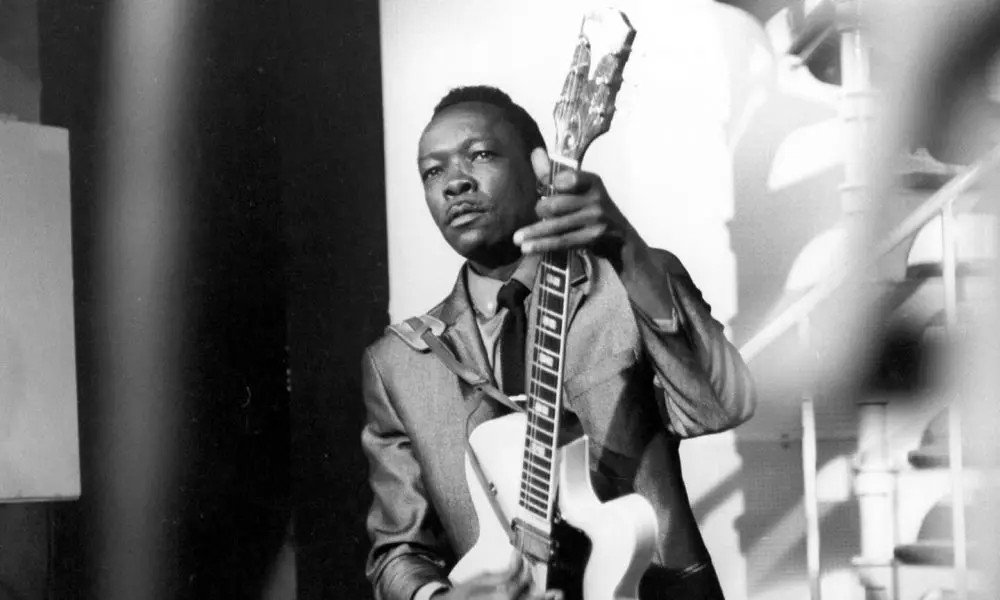

John Lee Hooker performing with his guitar

John Lee Hooker performing with his guitar

Photo: Michael Ochs Archives/Getty Images

John Lee Hooker wasn’t cut from the same cloth as his blues contemporaries. He lacked the commanding presence of Muddy Waters, the theatrical flair of Bo Diddley, or the raw intimidation of Howlin’ Wolf. Yet, John Lee Hooker was a bluesman who resonated deeply, a survivor who could move your soul and feet with just his guitar and his distinctive, hypnotic voice. He was streetwise, adaptable, and undeniably captivating. His music made you want to dance, to “boogie chillen,” as he famously put it. This exploration into the best John Lee Hooker Songs begins with that very anthem, his groundbreaking debut single that ignited a legendary career. Released in 1948, “Boogie Chillen'” wasn’t just a song; it was an invitation to find release and joy through movement, a testament to the blues’ power to uplift even amidst hardship.

Born on August 22, 1917, John Lee Hooker’s Mississippi upbringing as the youngest of eleven children to a sharecropper and Baptist preacher instilled in him a profound understanding of poverty. While raised in a religious household, his path shifted when his parents separated around 1921. His mother’s remarriage to William Moore, a blues guitarist with a droning, repetitive style, proved musically formative. Hooker absorbed Moore’s technique, later playfully referencing it in his 1971 track “Endless Boogie, Parts 27 & 28.” However, Hooker was far from a musical stereotype; his evolution would demonstrate remarkable originality. Further musical influence came from his sister’s relationship with bluesman Tony Hollins, who gifted young John Lee a guitar and taught him songs that would become foundational to his repertoire. Among these was “Crawlin’ King Snake,” a crucial John Lee Hooker song he first recorded and copyrighted in 1949. This shrewd move ensured royalties when rock artists like The Doors covered it on their LA Woman album in 1971, and every time Hooker himself revisited the track, which he did frequently.

Leaving home at 14, Hooker never returned to his family. He drifted to Memphis, navigating a tough life and playing at house parties. Like many from the South, he migrated north for work, landing a job at Ford in Detroit during World War II. Factory wages enabled him to trade his acoustic guitar for an electric one, amplifying his sound to match the city’s energy. He became a fixture in Detroit’s East Side clubs, and a demo recording led to a contract with Modern Records in Los Angeles. The release of “Boogie Chillen'” became an R&B chart-topper, launching John Lee Hooker’s illustrious career.

Boogie Chillen’

Click to load video

Following the success of “Boogie Chillen’,” “Hobo Blues” emerged as another R&B hit. Hooker’s career became characterized by a nomadic approach, shifting between record labels in pursuit of the best deals. He recorded for King Records as Texas Slim, Regent/Savoy as Delta John, and for smaller labels under names like Birmingham Sam and The Boogie Man. Despite the pseudonyms, his distinctive sound remained unmistakable. This label-hopping became a recurring pattern as numerous labels sought to release John Lee Hooker records. Modern Records scored another R&B number one in 1951 with “I’m In The Mood,” a suggestive song Hooker recorded eight times throughout his career, famously duetting with Bonnie Raitt decades later. Subsequently, Hooker moved to Chicago’s Chess label, leading to legal disputes with Modern over the single “Ground Hog Blues” in 1952. The contention highlighted Hooker’s growing star power; his raw, boogie style was unique and highly sought after. Modern eventually relinquished its hold on his complex career in 1955 with the single “I’m Ready,” perhaps unaware of the significant success Hooker was poised to achieve.

Signing with Vee-Jay Records, Hooker released “Dimples” in 1956. By this time, he was often recording with a full band, and this smoothly infectious song about an attractive woman enjoyed lasting popularity. Recognizing the burgeoning folk music scene in the US, Vee-Jay licensed Hooker to Riverside, a New York-based company, in 1959. This strategic move aimed to broaden Hooker’s appeal to a white audience. His two albums with Riverside, starting with The Country Blues Of, introduced tracks like “Tupelo Blues,” another John Lee Hooker essential. This song, recounting the devastating Mississippi flood in Elvis Presley’s birthplace, resonated with a sense of historical weight, similar to Howlin’ Wolf’s “Natchez Burning,” solidifying Hooker’s image as a bluesman deeply connected to his roots.

Another notable Riverside session produced “I’m Gonna Use My Rod,” later known as “I’m Bad Like Jesse James,” and “I’m Mad Again.” Hooker seemed comfortable embracing the folk label, even with his gun-toting lyrics, which contrasted sharply with the peace-and-love ethos of the emerging folk movement. For Hooker, the priority was likely financial compensation. His willingness to adapt and his numerous name changes earlier in his career demonstrated his pragmatism. Reinforcing his credibility within the folk scene, Hooker performed in New York in 1961, with Bob Dylan, in his big city debut, as the opening act.

Boom Boom

Click to load video

Beyond folk, a new market emerged for Hooker in London, where rhythm and blues was becoming the dominant sound in clubs. His songs became the soundtrack for the fashionable mod dances. “Boom Boom,” a contemporary track, was far from a folk ballad. This assertive, dance-oriented song about attraction reached the lower end of the US pop charts and, alongside a revived “Dimples,” became a staple in UK mod nightclubs in 1964. “Dimples” even reached the UK Top 30, and Hooker performed it on the popular TV show Ready Steady Go!. During 1963-64, Hooker’s collaborations extended into the Motown world, working with members of The Supremes, The Vandellas, and other Motown artists. Venturing into yet another genre, “Frisco Blues,” from the album The Big Soul Of John Lee Hooker, attempted to place him within a soul context. While recorded in Detroit with a Chicago label (Vee-Jay), the song’s inspiration surprisingly came from Tony Bennett’s “I Left My Heart In San Francisco.” This unlikely influence showcased Hooker’s unpredictable nature. Equally representative of his range was the regretful classic “It Serves Me Right,” also known as “It Serves You Right To Suffer,” from 1964.

In 1966, Chess Records again positioned him as a traditional artist with The Real Folk Blues, despite Hooker performing with a powerful band. The album featured “One Bourbon, One Scotch, One Beer,” a song with roots in Amos Milburn’s earlier version from the 1950s, which Hooker infused with his own style. Eighteen months later, shifting away from the “folk” label, Hooker released Urban Blues, featuring “The Motor City Is Burning,” his poignant commentary on the 1967 Detroit riots. The lyrics captured the city’s turmoil, depicting sirens, troops, snipers, and smoke, bringing the blues into a starkly modern urban landscape.

By the late 1960s, the hippie generation rediscovered the roots of rock and roll. Canned Heat, a band deeply influenced by Hooker’s boogie style, collaborated with him on the double album Hooker ‘n’ Heat. This marked the first of several collaborations and the first of his high-profile pairings to feature on any essential John Lee Hooker songs playlist. The album included a notable rendition of “Whiskey And Wimmen.” This wasn’t Hooker’s first foray into recording with white bands he had inspired; he had previously recorded an album in London with The Groundhogs in 1964, a band named after his song “Ground Hog Blues.”

Whiskey And Wimmen’ (Remastered 2005)

Click to load video

A series of studio albums for ABC culminated in Free Beer And Chicken in 1974, placing Hooker in a funkier setting with tracks like the self-explanatory “Make It Funky.” Throughout the 1980s, he released numerous live albums. A potentially major career boost narrowly missed when his appearance in The Blues Brothers film (1980) didn’t result in “Boom Boom” being included on the soundtrack album – possibly due to concerns that its raw authenticity might overshadow other tracks. However, a significant revival arrived in 1988, when Hooker, apparently 76 years old, released The Healer. This album featured rock stars eager to pay tribute to the blues legend. The title track, featuring Carlos Santana, gained considerable attention, and the album charted in the US, setting the stage for a financially and artistically rewarding later career.

Mr Lucky (1991), produced by Ry Cooder, replicated the formula, featuring collaborations with Keith Richards, Johnny Winter, and longtime admirer Van Morrison. Dressed in his signature suit, tie, and hat, the aged Hooker remained as compelling as ever. The award-winning Chill Out (1995) followed a similar collaborative approach with comparable guest artists, but adopted a more reflective tone. This album contributed “We’ll Meet Again” and a poignant version of his 1960s song “Deep Blue Sea” to the essential John Lee Hooker songs catalog.

Hooker’s final album before his passing in 2001, Don’t Look Back, was a moving work that still retained his boogie spirit. The title track held a particular poignancy, possibly reflecting Hooker’s awareness of his mortality. While he had recorded the song previously, this version carried a profound spiritual weight, serving as a fitting conclusion to an unparalleled career and a powerful closing track for any John Lee Hooker playlist.

uDiscover Rewards Program

uDiscover Rewards Program